Assam is fast turning into a proving ground for a dangerous experiment in demographic re-engineering, carried out under the convenient banner of immigration control. What is unfolding in the state today is not merely an administrative exercise to identify undocumented migrants; it is a systematic campaign that disproportionately targets Bengali-speaking Muslims, erodes constitutional safeguards, and reshapes Assam’s social fabric through fear and exclusion.

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s recent announcement—that individuals declared “foreigners” by Foreigners’ Tribunals (FTs) will be expelled within a week—marks a decisive and troubling escalation. Presented as a measure to improve administrative efficiency, the policy in reality strips due process of its already fragile protections. It revives and weaponizes colonial-era legislation, particularly the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act of 1950, to justify swift expulsions without transparency, accountability, or humanitarian safeguards. What is being normalized is not governance, but coercion.

The scale of the operation reveals its underlying intent. Since 2021, Assam has identified more than 32,000 individuals as so-called illegal foreigners, with state authorities openly declaring plans to expel 10,000 to 15,000 people annually. Between 2021 and 2025 alone, over 59,000 cases were disposed of by Foreigners’ Tribunals, resulting in more than 30,000 people being declared foreigners. Alongside these legal proceedings, recent reports of “pushbacks” across the Bangladesh border have emerged—carried out without public disclosure, judicial oversight, or bilateral mechanisms with Dhaka. These actions bypass both domestic legal standards and international norms governing statelessness and deportation.

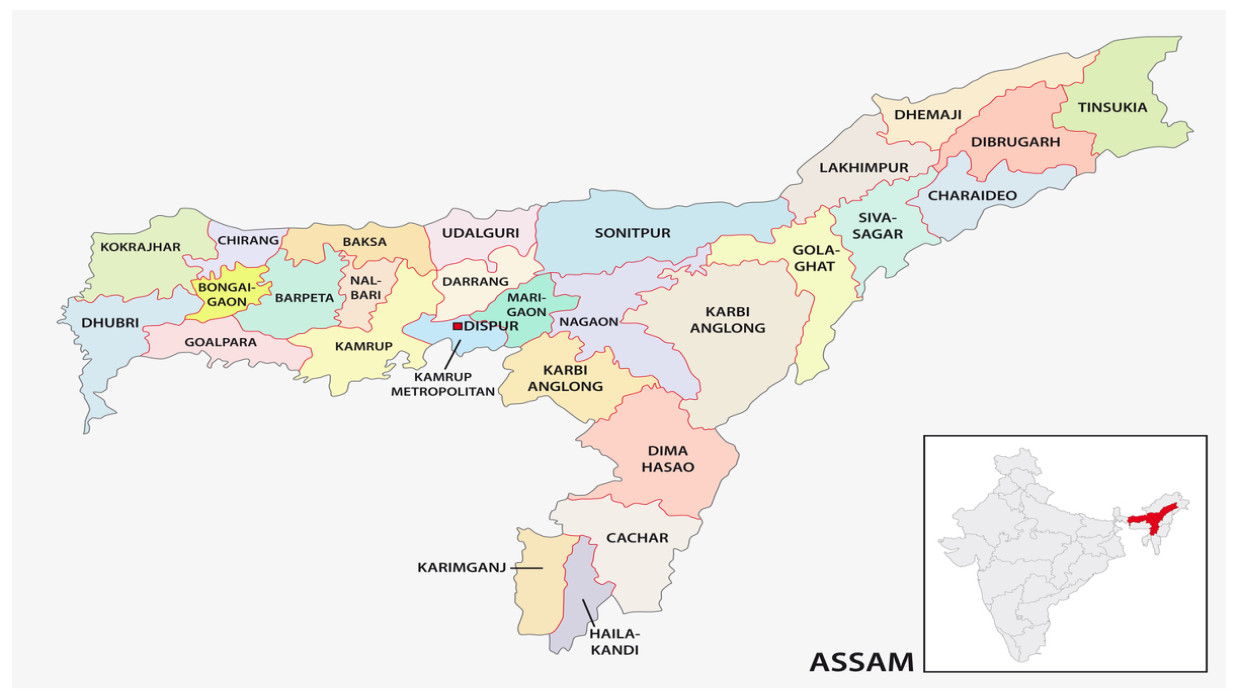

Assam’s demographic context makes these developments even more alarming. Muslims constitute roughly 34 percent of the state’s population—around 10.7 million people—with Bengali-speaking Muslims forming local majorities in border districts such as Dhubri and Goalpara. While the government avoids releasing data disaggregated by religion, the pattern of targeting is unmistakable. Bengali Muslims formed a significant proportion of the 1.9 million people excluded from the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in 2019, and they continue to be disproportionately ensnared by the NRC-FT apparatus.

The problem lies not merely in intent, but in design. The NRC and Foreigners’ Tribunals demand documentary proof that is often impossible for marginalized communities to produce—birth records from the 1950s, land deeds, or legacy documents that were never systematically issued or preserved. Floods, displacement, poverty, and illiteracy have further eroded access to such records. In practice, the burden of proof is reversed, forcing individuals to prove citizenship while the state assumes guilt. This is not border management; it is bureaucratic exclusion masquerading as legality.

What emerges from this process is a machinery of fear. Families are torn apart, livelihoods destroyed, and entire communities pushed into a state of permanent insecurity. Detention centers loom as instruments of coercion, while expulsion threats hang over people who have lived in Assam for generations. The specter of statelessness—condemned under international law—has become a lived reality for thousands, normalized as collateral damage in the pursuit of a political narrative.

At its core, what is unfolding in Assam is not about illegal migration. It is about reshaping demography to align with a Hindutva vision of India—one that equates national belonging with religion, language, and ancestry. By criminalizing Bengali identity and Muslim faith, the Indian state is hollowing out its own constitutional commitments to equality, secularism, and due process. Citizenship, once a legal status, is being transformed into a tool of majoritarian politics.

Assam’s experience should serve as a warning. When the state legitimizes collective punishment and administrative shortcuts in the name of security, it sets precedents that can be replicated elsewhere. Today it is Assamese Bengali Muslims; tomorrow it could be any community deemed inconvenient to the dominant political imagination.

Demographic engineering dressed up as governance is neither sustainable nor just. It corrodes democratic institutions, deepens social fractures, and replaces the rule of law with rule by exclusion. If India is to remain true to its constitutional ideals, Assam’s silent purge must be recognized for what it is—not immigration control, but a deliberate project of disenfranchisement with far-reaching consequences for the country’s pluralistic fabric.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published