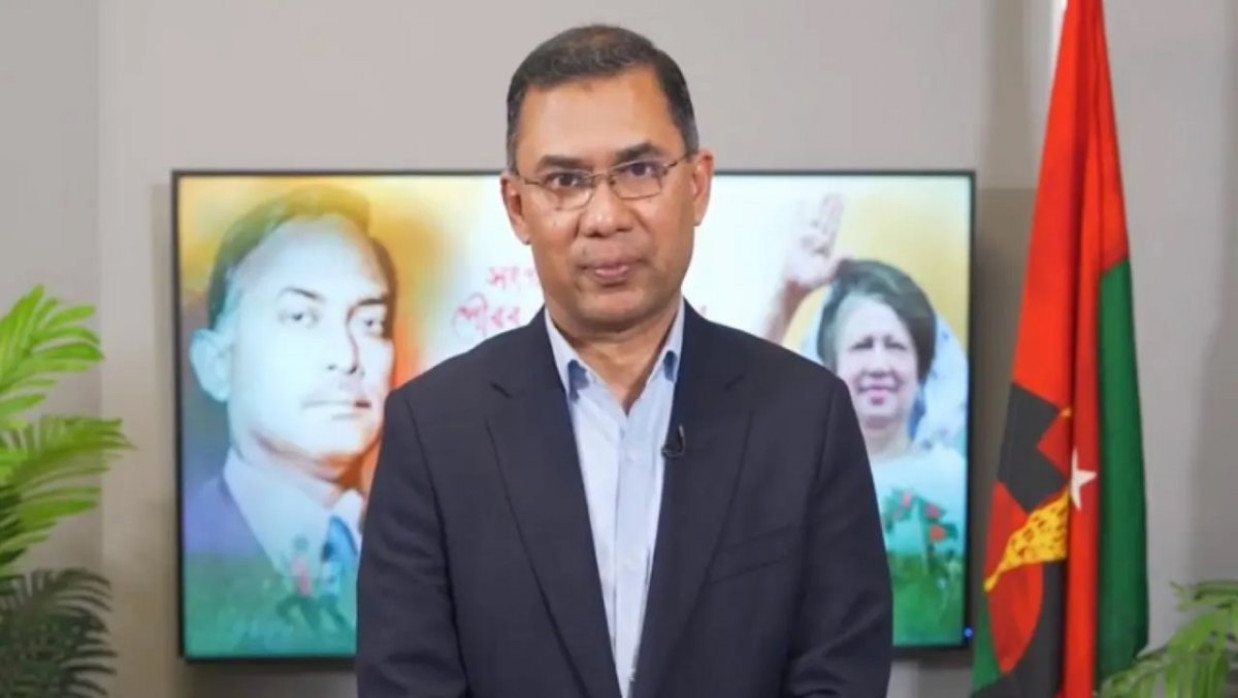

Youtube screen shot grab

This transcript of an interview between journalist Sreenivasan Jain and BNP Secretary-General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir isn’t perfect, but it has moments that cut through the typical rhetoric. Among sloganeering about “change”, some of the interview’s most important parts happen when Mr. Fakhrul is asked specific questions about corruption allegations against Tarique Rahman, and about what voters can expect from BNP if it returns to power.

The allegations: there is a pattern.

Journalists and analysts often refer to Tarique Rahman’s corruption allegations and convictions in bulk: “80-plus cases”, as if the details don’t matter. But when Jain presses Fakhrul on specifics, there’s one key takeaway: a handful of the most serious allegations were not campaign rhetoric, but sustained cases against Tarique Rahman that worked their way through Bangladesh’s courts and official investigative agencies for years. Some of those allegations were substantiated with evidence marshalled by Bangladeshi officials, and by testimony from foreign officials, including in a Singapore-based money laundering investigation into transfers allegedly tied to winning a power plant contract.

We should keep the political context in view. Political opponents openly debate whether Bangladesh courts and law enforcement were weaponized during the Awami League’s two-decade rule. Those accusations are credible in part because they’re true. But criticisms of Tarique Rahman must hold two concepts simultaneously: first, that authoritarian misuse can motivate politically charged allegations, and second, that proven state misuse doesn’t inherently invalidate prosecutorial evidence.

Do those corruption charges have merit?

The answer is more complicated than yes or no. Since 2024, Bangladesh’s courts have reversed several convictions linked to Tarique Rahman. In March 2025, Bangladesh’s Appellate Division acquitted Tarique Rahman and Ghiasuddin Al Mamun in connection with the Singapore money laundering case. In May 2025, Bangladesh’s High Court acquitted Tarique Rahman and his wife, Zubaida Rahman, in an illegal wealth case in which previous judges had convicted Rahman in absentia. Bangladesh’s High Court also acquitted Rahman in connection with the grenade attack case from 2004 in December 2024.

These rulings don’t necessarily prove Rahman’s innocence or that the allegations were false. That’s an important distinction. A court's acquittal of someone is not the same thing as vindication. But multiple acquittals shift the burden of persuasive evidence: if you tell voters “he is proven corrupt,” you have to account for why Bangladesh’s highest courts took that position away from you. That doesn’t mean Tarique Rahman is innocent; it means someone who raises allegations against him must explain these court decisions.

At the same time, questions about due process don’t flow in one direction. Courts can drift during political transitions. Verdicts can be rushed through an overburdened system. Donor pressure can incentivize guilty verdicts. High-profile legal reversals years into democracy, which some legal analysts have described as “political exoneration,” merit their own criticism. Jain raises these concerns pointedly at one point in the interview.

How well did Mirza Fakhrul respond?

Emotionally, Fakhrul succeeds. Rhetorically, he does not. Fakhrul’s answer to specific allegations against Tarique Rahman amounts to this: none of it happened. When pressed, his argument withers into a blanket refusal to accept any judgments about Rahman’s actions or character, including judgments from courts and modern journalism. Fakhrul calls several cases “baseless”, finds negative media coverage about Tarique “very strange”, and says the testimony of investigators from Singapore’s Corruption Investigation Branch is “nothing but a conspiracy.”

Critics will see through this. Anyone who has followed Bangladeshi politics will know BNP was a political prisoner party for years. Opponents were imprisoned, and protests were suppressed. The BNP’s student wing was systematically suppressed, its leaders arrested, and its presence on campuses effectively eliminated under the Awami League government. Much of the public will sympathize with Fakhrul’s posture. But this is not how a persecuted opposition party wins back voters' trust after a repressive tenure. You don’t prove your party is reformed by telling people “you can’t trust anyone.”

A stronger answer might have conceded selective justice under the Awami League, while arguing Tarique Rahman was unfairly targeted or that he’s been exonerated by court decisions. A better answer would have cited court decisions, committed to transparency in asset declarations, and accepted oversight from ACC or ICT investigators. Fakhrul does none of these things.

Instead, his answers circle back to attacking the interviewer. “You are deliberately trying, attempting, to tarnish the image of BNP and wanting to malign…Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and Tarique Rahman.” Frustration with media critics is real; intimidation against reporters is not new. But when a ruling party or political leader reacts to accountability by insulting the asker, it accomplishes one thing: convincing everyone you have something to hide.

What’s “Tarique’s plan?”

Opposition leaders have promised supporters that Tarique Rahman has a plan to change Bangladesh. In the interview, when pressed about what Tarique plans to do if accusations resurface, Fakhrul again replies by speaking vaguely of plans “for the future of Bangladesh.” Tarique Rahman has said publicly that he wants to project an inclusive national identity. “Bangladesh belongs to all Bangladeshis… Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, and Hindus,” he tweeted in March.

That’s fine. Whether you like it or not.

But does BNP have a plan to prevent corruption? Will it reform procurement? Will it hold police accountable? Will it crack down on party members who engage in extortion? Can minorities trust the courts to protect them if the BNP comes to power? Fakhrul’s answers about Tarique Rahman suggest he either can’t or won’t say: when pressed, he pivots back to criticism of the interviewer.

Can Bangladesh trust Tarique Rahman with power?

The true test of trust isn’t asking voters to look the other way. It’s accepting accountability when allegations arise. Bangladesh voters should closely watch how allegations against Tarique Rahman are investigated if the BNP wins power. Will BNP supervise the Bangladesh courts? Probably not. Will Tarique Rahman face justice if compelling allegations are brought? It’s unclear. But after years of misgovernance on both sides, what voters should remember from this interview is how little the BNP is saying about its plans to prevent repeat offenses at all levels: systemic corruption, strongman rule at the local level, and yes, corruption at the top.

BNP can credibly argue it was a victim of politicized prosecutions. Fakhrul alludes to it several times. But he never once addresses voter concerns about impunity within the party’s own grassroots networks. This is as close as he comes: “Maybe there are some cases…we can say that happens when there is a change.” That, followed by immediate denial and deflection.

BNP wants voters to trust it with power. Fair enough. But if the party wants to earn a mandate from the Bangladeshi public, it should treat this election as a new constitutional moment. Publish a white paper on its anticorruption plans. Strengthen internal party disciplinary processes. Protect an independent ACC and judiciary from political interference. Insist that all top leaders file public asset declarations that can be independently verified. Until they do that, Rahman’s return will seem less like reform and more like replacement.

Neither this interview nor Tarique Rahman’s court cases proves corruption. But they do prove the party will face allegations if it returns to power. Voters shouldn’t ignore those allegations; they should demand answers about how BNP will prevent future corruption at every level. If BNP cannot explain that, then asking the public to trust Rahman with power is not accountability. It’s hubris.

And in a post-uprising nation desperate for credible answers, that may be the worst optics problem of all.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published