Since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan last year, the country has faced a humanitarian crisis with half of the population experiencing acute hunger. The U.N. Refugee Agency says 3.4 million Afghans are internally displaced due to conflict, the country’s healthcare system is experiencing severe shortages, and workers in schools and hospitals are going without salaries while facing rising food and energy costs — which many attribute to economic restrictions the Biden administration implemented. We look at the unfolding crisis in Afghanistan with journalist Matthieu Aikins, formerly based in Kabul, who went undercover with Afghan refugees to write his book, “The Naked Don’t Fear the Water,” following their journey crossing borders to the West. “It’s very stark, the difference in treatment between the vast majority of refugees who need smugglers to escape and what’s happening in Ukraine right now,” says Aikins. He is a contributing writer to The New York Times Magazine, where in his latest piece he raises the question: Who does the West consider worthy of saving?

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we turn now to Afghanistan. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi visited the Afghan capital of Kabul this week and urged the international community not to neglect Afghanistan, where more than half the population is experiencing acute hunger.

FILIPPO GRANDI: When the entire attention of the world is focused on Ukraine, and, by the way, on the refugee crisis that Ukraine — the Ukraine war is producing — and rightly so, because it’s big, it’s serious — I thought it was important to pass the message that other situations which also require political attention and resources should not be forgotten and neglected, especially Afghanistan.

AMY GOODMAN: Afghanistan has faced a looming humanitarian crisis since the Taliban took control last August, with millions on the brink of starvation. The U.N. Refugee Agency says 3.4 million Afghans are internally displaced; another 2.6 million Afghans have fled Afghanistan as refugees.

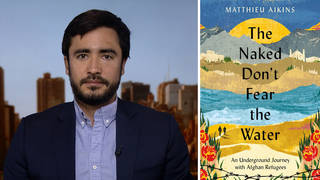

To discuss all of this, we spoke to the award-winning journalist Matthieu Aikins, contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, who has reported on the U.S. occupation and war in Afghanistan since 2008. He’s written a remarkable new book. It’s called The Naked Don’t Fear the Water: An Underground Journey with Afghan Refugees. In his New York Times essay, headlined “’We’ve Never Been Smuggled Before,’” he writes about Afghans who are trying to escape their country as its economy is collapsing. Nermeen Shaikh and I recently interviewed Matthieu Aikins. I began by asking him to answer a question he poses in his article: Who does the West consider worthy of saving?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Imagine right now if Ukrainians, instead of being allowed to cross freely into neighboring countries, into the EU, where they don’t require visas — imagine if they were being forced to cross the mountains and sea with smugglers and risk their lives just to escape this war. And that, of course, is the situation for Afghans, as it was for Syrians, as it was for people in most conflicts in the world. They’re caged in by these borders. They’re not able to cross freely without visas.

And when I went to Afghanistan this summer and fall, I went to the border with Iran and witnessed a new wave of Afghans who are displaced, who are fleeing their country, and spoke to a young couple there named Jawad and Shukria, who are the subject of this article that you mentioned, and they had decided to escape the Taliban and were facing this deadly journey through the desert in order to reach safety. And that, unfortunately, is the situation for Afghans.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Matt, on the question of refugees and where Afghan refugees have been able to enter, the vast majority of which were in — of whom were in Afghanistan — sorry, in Pakistan and in Iran, but then, more recently, it’s been harder for them to even enter those countries.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Yeah, and they need visas, in most cases, and they’re not easy to get. The passport office wasn’t working. This young woman, Shukria, didn’t have a passport before the collapse, and so she couldn’t get one. Even if they do have one, they can’t get visas to the majority of countries. I mean, Afghans have one of the worst passports in the world when it comes to visa-free travel. And that’s actually deliberate. These visa laws are put in place to keep out asylum seekers which the West doesn’t want. So, it’s very stark, the difference in treatment between the vast majority of refugees, who need smugglers to escape, and what’s happening in Ukraine right now, which is, of course, good. People should be allowed to flee wars without having to resort to smugglers.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Matt, before we go to the situation, the political situation, in Afghanistan now — and, of course, later, your book — if you could talk about the humanitarian crisis? As we said in the introduction, 75% of Afghanistan’s population has now fallen into acute poverty, 5 million Afghans facing acute malnutrition, and the U.N. secretary-general warning that the country was hanging by a thread. Could you talk about what you know of the causes of this crisis and what you think needs to be done?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, one thing we have to understand is that there’s been a malnutrition, a poverty crisis in Afghanistan for a long time. Poverty and malnutrition actually got worse during the U.S. occupation, because of the conflict and because of the ineffectiveness of development and aid. But, of course, the collapse has made it far worse. You know, we, over 20 years, built the most aid-dependent state in the world, perhaps in history, and the sudden withdrawal of that aid has had predictable consequences. It’s led to this near collapse of the government and a situation where people don’t have enough to eat, where they’re, in some cases, selling their children, you know, in very young marriages in order to survive, where they’re fleeing across borders just to find jobs. So people are fleeing a catastrophe that we have direct responsibility for. But under the refugee laws that we have today, that wouldn’t count — that doesn’t make them eligible for asylum. You know, someone fleeing starvation is not considered a refugee in the classic definition of the term, the Geneva Convention of 1951. And yet that is absolutely what’s driving a lot of Afghans to leave their country.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You said, Matt, that a humanitarian crisis is not grounds for Afghans or others seeking asylum refugee status. But in addition to the humanitarian crisis, there have been widespread reports of the Taliban cracking down on women, women activists, former members — members of the former government, as well as on journalists. I mean, are those people still trying to flee the country?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: They are. But like I said, it’s very difficult to leave. You know, people are facing risk of persecution. I have friends there. You know, every day I wake up to messages on my phone, people who are desperate to get out. It’s very, very difficult for them to get visas and leave. And once they do, even if they can get to a neighboring country like Iran or Pakistan, they’re looking at waiting years for refugee resettlement. But there’s a lot of people who are trying to get them out. These are people who want to leave, who have people in the West who want to help them get out, support them. They’re people we have a responsibility for, due to our long involvement in the country and the mess we’ve left behind. And yet, again, because of visa restrictions, because of immigration laws, because of man-made constraints, these people are trapped in a desperate situation.

And so, that’s really, I think, what we should be aware of. And one of the things I wanted to explain in my book is just how much of the suffering and restrictions faced by refugees, faced by migrants, are the result of border policies, are the result of laws. And it really takes a case like Ukraine, where people are just leaving — you know, they’re just getting in their car and driving to Poland — for us to see just how much of the suffering is actually unnecessary in places like Afghanistan.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s take a deep dive into your book, because you tell this story so graphically, what happens to refugees, you know, those who are, quote, “worth saving” and those who aren’t. Matthieu Aikins’ book is called The Naked Don’t Fear the Water: An Underground Journey with Afghan Refugees. We have a rule on Democracy Now!, Matt, and that is no soundbites. So you’ve got to give us the whole meal here. Can you talk about the journey you took, the obstacles, the horror people face when they’re fleeing a desperate situation, which is what you could describe Afghanistan, the country, as over the last decades of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Afghanistan? Talk about your journey.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, the story begins with my friend, whom I call Omar in the book. And Omar was one of the first people I met in Afghanistan when I went there, shortly after I went there in 2008. He had grown up in exile. His parents fled the Soviets. You know, we have to remember, Afghanistan has been at war for 40 years now, tragically. And they came back after 2001 full of hope for the future of their country, for this era of development and peace that the West had promised to Afghans after the Afghan invasion. And he became a translator with the American military. He was also working for Canadians. He spoke English. Then he decided he wanted to work with journalists, so that’s when we met. And we worked together for many years in the country while I was living in Afghanistan. I got to know his family, as well. And like many Afghans, he dreamed of emigrating to the West. He actually applied for one of these special immigrant visas that the U.S. grants to employees, local employees in Afghanistan and Iraq. He should have qualified, but because of all the paperwork restrictions, he was rejected.

So, this happened in 2015, when, as you probably recall, there was a migration crisis in Europe. A million people crossed the Mediterranean Sea — it was the largest movement of refugees in history — in these little rubber rafts. So, the borders in Europe opened briefly, and Omar thought, “This is my chance to go.” So he decided to take the smugglers’ road to Europe in order to escape. And I decided to go with him. But the only way that I could do that was to go undercover as an Afghan refugee myself, because of the danger of being kidnapped or being arrested and separated. And because I have — my mother’s ancestors are Japanese, but I look Afghan and I speak Persian, from living there for so many years. So I was able to do that. So, the book is a story of our journey together through the migrant underground to Europe.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the journey you took. Talk about where you started with your friend Omar and what you faced.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, it started in Kabul, when he decided to go. And he was on the fence about leaving for a while, because he had fallen in love with, you know, a young woman, the neighbor’s daughter, and he didn’t want to leave and risk losing her. But, ultimately, he realized that was the only way her father, who didn’t want the marriage to happen, was going to give him her hand, because he needed to go and have something to show he could bring her legally to Europe perhaps. So he made the decision to set off.

And we traveled to the border, the same place I was last fall. You know, this is the Iranian border. It’s a desert between Iran and Afghanistan, and this is where migrants cross. It’s a very dangerous journey, takes you through wild terrain controlled by drug smugglers and insurgents. So, we ended up at a smugglers’ safe house there. And there were many twists and turns, which I guess I shouldn’t get into here, but eventually we found ourselves in Turkey. And then, from Turkey, we went to the coast, again with smugglers. And we were driven to the beach and deposited around midnight and told to get on board a little rubber raft. So, there was about 40 people, men, women and children, some of them Syrian, some Afghan, some African. But we were all together in this tiny boat that set off into the sea around midnight. And that was the crossing that many refugees made in hopes of reaching safety on the Greek islands.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Matt, you said that Omar himself grew up in exile. He didn’t grow up in Afghanistan. He and his family returned to Afghanistan in 2001 after the Taliban were ousted. Where did he grow up? And then, also explain the role of smugglers, who they are, and the exorbitant sums they often charge people trying to flee.

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Yeah. They do often represent, you know, the life savings for people, these sums of money that they have to pay. And the more money you have, the safer your journey. And the less money you have, the more risks you’re forced to take. But the fact of the matter is, as I mentioned, almost every refugee needs a smuggler because they’re not allowed to cross borders. They don’t have — they come from countries normally where their passports don’t allow them to travel. So smugglers are a necessity. They’re often scapegoated for the migration crisis, but, in reality, they’re created by borders. You know, the harsher a border is, the more difficult it is to cross, the more people are going to be willing to pay smugglers, the more of an economy it creates.

And this is something Afghans have lived with for decades. You know, like I said, Omar grew up in Iran, and he and his family were also in Pakistan. They were on the move throughout his childhood, and very often they were crossing borders with the help of smugglers. And one of the things that I talk about in the book in terms of history is how these borders have gotten more and more difficult to cross over time. So, when they were fleeing the Soviets at that time, it was actually relatively easy to cross. In some places, you might just pay a small bribe to a border guard. But over the years, as neighboring countries have tried to keep out Afghan migrants, they’ve built walls, they’ve stepped up patrols, they’ve increased the violence at the borders. That’s just meant that people had to pay more and go further, take deeper detours into the mountains. The bribes that are paid now have increased. The cost has increased.

And yet people are still crossing. And yet, you know, there’s been a massive wave. You know, when I was on the border this fall, we saw — I was told by smugglers there that they’ve never seen this many people crossing. There was an estimate that maybe a million Afghans have crossed into Iran this fall. So, the borders don’t keep people out, they don’t keep desperate people from moving, but they do enrich smugglers.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the things you expose, Matt, was the drone strike at the very end — the last one that the world saw because all the world’s media was there, though that had happened many, many, many times before throughout Afghanistan, where there weren’t witnesses, where there weren’t journalists, creating so many internal refugees, who then ultimately are the refugees who try to leave the country. And I wanted to connect it to something that just happened a few weeks ago in the Senate.

In January, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the costs of 20 years of the U.S. drone strikes. The hearing began when the committee chair, Senator Dick Durbin, played a clip from Democracy Now! of a Yemeni victim of a U.S. drone strike. Among those who testified was Hina Shamsi, the director of the National Security Project for the ACLU, which represents survivors of the August 29th drone strike in Kabul that you so well documented, that killed 10 Afghan civilians.

HINA SHAMSI: I’ve listened to fathers describe the horror of having to pick up the body parts of their children. I’ve listened to one of my clients struggle to breathe through her despair after the killing of her husband, an aid worker for an American NGO, and three of her sons and one of her grandchildren. My clients’ grief is compounded by the fact that for 19 days our government kept up false allegations about their loved ones, wrongly asserting the strike was righteous and successful against ISIS operatives. The Pentagon later admitted its mistake, but the damage is done.

AMY GOODMAN: Hina Shamsi’s testimony drew an angry response from the South Carolina Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, whose second-biggest source of campaign contributions for his 2020 reelection campaign were employees of the major drone producer Lockheed Martin. This is Senator Graham.

SEN. LINDSEY GRAHAM: Afghanistan is a breeding ground for terrorism as I speak. Everybody that we work with is being slaughtered. And we want to talk about limiting — closing Gitmo and restricting the drone program. You’re living in a world that doesn’t exist.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s Lindsey Graham lecturing Hina Shamsi. Matt, can you describe the world that does exist, as you saw it, with the U.S. drone strikes in Afghanistan?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: Well, yeah, I was there the next morning after this drone strike in Kabul, and I saw some body parts in the wreckage of the vehicle that the U.S. had destroyed inside a family home. Some of those body parts belonged to the seven children who were killed in the strike. And as you mentioned, this strike was one of many. You know, this was well documented because it happened in Kabul at a time when the world’s attention was focused, but there’s countless strikes that have taken place in remote areas where people can’t visit, and we just have the military’s version of events.

But, you know, the point is right now that we have a direct responsibility for what has happened in Afghanistan. There’s no easy solutions. I don’t think just sealing off the borders and bombing them with drones is in any way going to help the situation, and it’s not reflective of the responsibility we bear. We should be working to actively alleviate the humanitarian crisis as best we can. Instead, we’re cutting off the Afghan central bank’s funds and seizing it, saying we’re going to distribute it to the 9/11 families. So, I think people would just like to turn their backs on Afghanistan and forget about them, but the truth is that we have much more responsibility for what Afghans are fleeing than Ukrainians, for example.

AMY GOODMAN: And if you could explain that last point? It’s one that we have focused on a lot. But this issue, if we could end on these sanctions against the money? We had on a mother whose son was killed in the 9/11 attacks, Phyllis Rodriguez, and she said, not in her son’s name does she want the people, the sons and daughters of Afghanistan, to suffer as her family has suffered losing him. This point of the sanctions put on the aid to Afghanistan that is preventing the people of Afghanistan from getting their money?

MATTHIEU AIKINS: What we’ve done is we’ve frozen deposits that the Afghan central bank had in U.S. banks. And that has completely crippled the financial system and exacerbated the terrible crisis that’s happening in the country. And, you know, to seize this money and say you’re going to distribute it the 9/11 families, to me, is not only cruel, but illogical, because this money doesn’t belong to the Taliban, right? It belongs to the Afghan people. If we don’t recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, which we haven’t, then it’s not their money. But it’s clearly a policy that’s being done for domestic reasons, for domestic political reasons. And I think it is sadly representative of an administration that clearly is not thinking about Afghans first.

AMY GOODMAN: Award-winning journalist Matthieu Aikins, author of the new book The Naked Don’t Fear the Water: An Underground Journey with Afghan Refugees.

Oh, and this update: Earlier this week, the Biden administration designated temporary protective status, or TPS, for Afghanistan, which will protect Afghan refugees from deportation for 18 months, including the 76,000 who fled after the U.S. military withdrawal and arrived here before March 15th. The move came about two weeks after Biden granted TPS to Ukrainians.

And that does it for our show. Happy early birthday to Tami Woronoff!

Democracy Now! is accepting job applications. You can go to democracynow.org.

Democracy Now! is produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Camille Baker, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud, Mary Conlon, Juan Carlos Dávila. Special thanks to Julie Crosby. I’m Amy Goodman. Stay safe.