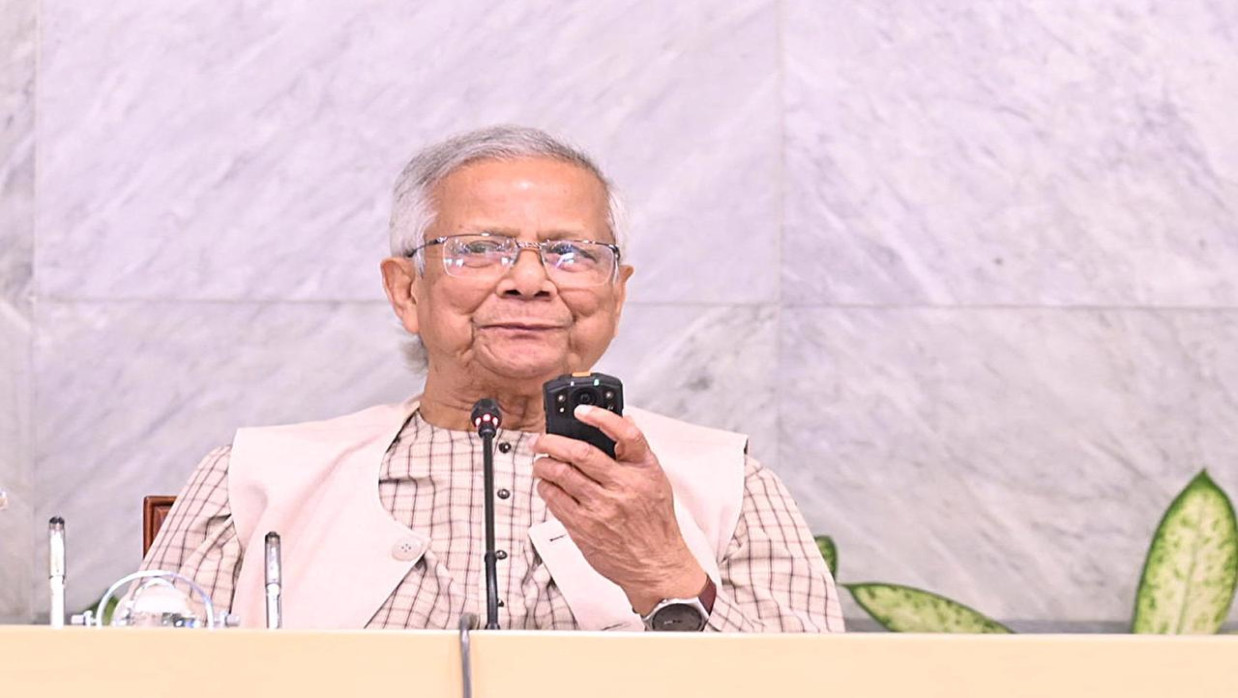

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus did not assume the highest office in Bangladesh as a politician seeking power and authority. Instead, he did so as a reluctant leader, summoned by the hour when the nation stood at a critical juncture in its history. In moments like these, leadership is not about ambition or the desire to exercise power; it is about responding to the call of history. Yet there is a paradox to such moments when the moral high ground is forced to operate from the center.

Over the 18 months of the Interim Government, the sentiment among the people of Bangladesh across vast sections of the population was one of sustained and even emphatic endorsement. The reform-minded citizens and the growing middle class in the urban centers saw Yunus as a vehicle for institutional renewal and democratic rebalancing.Top of Form

Bottom of Form

It is a question of perception and a deeper understanding of the nature of transition and governance: being a reformer is not the same as being a ruler.

From Respect to Recalibration

Prior to the events of July-August 2024, which led to the nation's transition period, the nation’s leader was viewed in a distinct manner within elite circles of civil society. While he was viewed favorably as a figure of international acclaim and moral stature, a Nobel laureate and pioneer of the microfinance movement was not necessarily viewed warmly.

In fact, many members of the elite circles of civil society viewed him as a brilliant intellectual but a disruptor of the status quo. The events of 2024 recalibrated how the nation's leader was viewed. In taking the reins of the Interim Government, the nation's leader transitioned from a figure of moral commentary to one of governance. Governance is a process that recalibrates perception.

Reform, accountability, and stability are not necessarily incompatible objectives, but they are not necessarily perfectly correlated either. Seizing one of these objectives with great vigor may temporarily disrupt another. By trying to recalibrate the state institutions, enhance accountability, and lay the groundwork for credible elections, Yunus was bound to alienate constituencies that initially saw as a source of hope.

That is the reality of leadership in transitional societies. The comfort of universal goodwill is often sacrificed in the course of difficult decisions.

Controversies and Civil Liberties

Some of the discomfort, however, also came from controversies surrounding specific decisions.

One of the controversies surrounding Yunus was his perceived closeness to student movements and populist forces that played a large role in remaking the country’s political landscape. Whether this was strategic engagement or merely rhetorical solidarity with these movements is debatable. What is not in doubt, however, is that to some of the elite circles that perceived him in a different light, Yunus’s perceived closeness to these forces was seen as a gesture of embracing the rhetoric of populism, fair or unfair as that perception may have been.

The more troubling allegations, however, concerned the government’s perceived tolerance of arbitrary detentions during the transition period. Whether these detentions were intended to stabilize the state or to address security threats, they also raised uncomfortable questions about civil liberties.

For a man whose global reputation was built on being a force for good in governance, social justice, and empowering the marginalized, these allegations of arbitrary detentions cut very deeply into his moral brand.

The conflict between moral expectation and political reality was unavoidable.

Elite Opinion and Political Memory

However, it would be naive to assume that Yunus is overly concerned with elite opinion. There are grounds to believe that he regards certain sections of Bangladesh's civil society with detachment.

In the later years of the Sheikh Hasina government, during which Yunus himself was under political and legal pressure, sections of the elite remained muted. This may be relevant.

Second, politics is a fluid domain. Alliances change. Yunus is also aware that, although he has lost some of his earlier support base, he has managed to build new alliances, particularly with young reformers, sections of the diaspora, and with those abroad who view his stewardship as a force for stability during a difficult time.

Politics, after all, is not about universal popularity. It is about long-term legitimacy.

The London Meeting and the Presidency Question

Rumors of a meeting between Yunus and Tarique Rahman, the acting chairman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), surfaced in London. It has been reported that, either explicitly or implicitly, Rahman discussed with Yunus the possibility of his becoming president of Bangladesh if the BNP returned to power.

Those close to Yunus deny this. They claim that Yunus has no interest in becoming president. He wants to return to his earlier life of social business innovation, ethical capitalism, and development politics.Politics, of course, is a constantly changing game.

The constitutional amendments under discussion would grant the president greater powers. This would elevate an office that has traditionally been ceremonial to one of greater significance.

In this context, the office of the president is not just symbolic; it is structurally important.

Rahman himself may now see the irony in the situation. A stronger presidency requires an accommodating individual to guarantee executive branch synergy. Intellectual freedom and global reputation are not qualities Yunus is likely to display in the role.

Why a Yunus Presidency Would Be Important

Yet, paradoxically, a Yunus presidency may provide Bangladesh with considerable strategic benefits.

Yunus, despite criticism from certain segments of the population within Bangladesh, still possesses an unprecedented level of respect and reputation abroad.

No individual from Bangladesh, nor arguably from the entire Third World, possesses such an esteemed reputation within global financial institutions, the development community, the West, and the multilateral system.

In an environment where Bangladesh must balance its geopolitical relationships with India, China, the US, and the Gulf states, an individual with such an esteemed reputation may prove valuable.

A domestically-oriented Prime Minister, focused on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration, the economy, and political alliances, paired with an internationally-oriented President with a reputation to uphold, may provide Bangladesh with a dual-track system of governance.

This system is not unprecedented in a parliamentary democracy.

Clearly, there are prerequisites such as role definition and mutual respect; however, when it functions properly, it may prove beneficial.

Reformists, Reputations, and the Judgment of History

Transitional leaders are not without scars. Governance often complicates reputations established in civil society or academia.

The test is not whether or not Yunus maintained an impeccable reputation among the population no politician does.

The test is whether or not he left a mark on the stability and continuity of the institutions and the democracy he served.

History does not judge reformers on the level of comfort they provide the political and social elite.

History judges leaders on the stability they provide the nation.

If Bangladesh’s democratic institutions emerge from this period stronger, more accountable, and more credible, then elite skepticism may fade into a footnote.

And should the question of the presidency arise again, it will not be about ambition or accommodation.

It will be about whether Bangladesh wants symbolic stature, structural authority, or a judicious blend of both.

In seasons of transition, reputations may flicker, rise, and recede with the shifting winds of opinion but legacies are forged in consequence, measured not by applause or dissent, but by the enduring imprint a leader leaves upon the destiny of a nation.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published