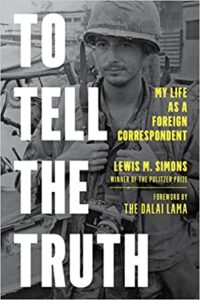

To Tell the Truth: My Life as a Foreign Correspondent, by Lewis Simons, Foreword by the Dalai Lama, Bowman & Littlefield publisher, Lanham Md, USA, 2022, 278 pages, ISBN: 978-1-5381-7316-9. Hardcover $ 35.00.

By Arnold Zeitlin 9 December 2022

India can be a challenge, Pulitzer-Prize-winning reporter Lewis Simons writes in a memoir that covers significant time in South Asia over a career that spans 60 years and is continuing. In his case, the country was a challenge he lost.

As the correspondent based in New Delhi for The Washington Post, Simons was responsible for covering all of South Asia, including India’s deadliest rival, Pakistan. It was the new Pakistan prime minister after the fallen Yahya Khan regime who contributed to Simons’ downfall.

Firstly, in Simons first visit to Islamabad in 1972, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, obviously aware of who reads The Post in Washington, promptly granted him an interview during which, Simons writes, he was not only “surprisingly candid” he offered the reporter a tipple of Scotch whisky. In comparison, a year before I had met Bhutto in Lahore, tripping on a rug on my way out. “And he doesn’t even drink,” Bhutto muttered as I almost fell.

At any event, Simons found the American-educated Bhutto “quite charming” and interviewed him on frequent, subsequent reporting trips to Pakistan.

Secondly, eventually, S.K. Singh, India’s official spokesman, summoned Simons to the foreign ministry. His reporting was one-sided, Singh said. “They make Bhutto look good and cast Mrs. Gandhi in a negative light,” he complained, referring to India’s prime minister, Indira Gandhi.

Simons responded that Bhutto granted an interview every time Simons asked and writes, “it was natural his views would make their way into my copy.” Mrs. Gandhi had never given him an interview. Singh “sighed knowingly and rolled his eyes,” Simons wrote and promised to press the prime minister for a Post interview.

None ever occurred.

Instead, thirdly, three days after Gandhi imposed a national emergency in June 1975, three armed police hustled Simons from his office. He was held in a hotel until forced to leave on the next flight from India to Bangkok.

Had Simons lost his challenge with India? Perhaps. In a fit of pique, the Gandhi regime cut ties with an influential U.S. newspaper. The newspaper continued to cover India, but remotely. Like many other regimes which oust reporters, the Gandhi government lost the opportunity, which Bhutto had seized, to expose its views to a significant American readership. Eventually, times change: Simons returned to India in 1984 to cover the funeral of the assassinated Indira Gandhi.

For those readers interested in how an American reporter works from overseas, Simons work in South Asia provides a primer. Covering the story of drought and famine in India, Simons writes: “The most effective why I knew to make it grab readers’ attention was to people it with those living on the parched soil.” In his first visit to Bangladesh in December 1971, he hunted for and found a victim of Pakistan army rape for his story. For a story about what was then called Calcutta, he had jogged for an hour in 90F-degree heat alongside a barefoot rickshaw puller, a man who ran all day to make a living.

The memoir is unusual for having a persistent sub-story running under the descriptions of simons’s decrying do. The story is about his marriage.

He and his eventual wife, Carol, met on their first day in New York City as members of the class of 1964 at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, where young people dream of distinguished careers in journalism. They married in 1965. Simons went on to four bureau chiefs abroad and a Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles that helped bring down Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos. Carol went on to have three babies and, while doing a series of freelance work and often significant editing jobs, pretty much tended to the domestic side of this marriage. When her husband was ousted within hours from India, she was left suddenly to deal with a hostile government that refused to let her leave and closed the family’s bank account. In tears, she attended the U.S. embassy’s July 4th celebration, where the American ambassador ordered she get help. The next day, an embassy car drove her and her children past immigration and customs at the New Delhi airport right onto the tarmac, where she boarded a flight to Bangkok and Simons.

While many of these sorts of journalism marriages have filed, the Simons’s has endured for more than 50 years. Simons has told the stories of his career and marriage often in blunt prose that serves to illuminate the humanity involved in the life of

both himself and his wife. He offers a read that rises above the usual gung-ho journalistic memoir.