Two weeks ago, I wrote of the death of Pervez Musharraf; or rather I wrote of his short life of 10 years as the leader of Pakistan. He was thrust into that role by happenstance. That was not so long ago, and most readers will probably have at least some hazy memory of the string of coincidences that took him from Lt. General to General and Chief of Army Staff (COAS), to President of Pakistan, without any sign that he had the political ambition or political experience. But I wonder if they realize how really accidental a leader he was, and how unprepared he was to lead a country as politically complicated and difficult as Pakistan.

Musharraf became President not because he or the Army planned it that way but because the civilian government threatened its hold on the hybrid power it held in the hybrid political setup that had evolved in Pakistan. Though it went unrecognized at the time, as COAS, Musharraf showed his political naivete by planning and authorizing the Kargil fiasco, the covert incursion by the Pakistan Army into India, in early 1999 which, when discovered, raised the specter of a nuclear exchange between the two nations, and ended up with a humiliating Pakistani political and military defeat. Later, after the military coup d’état made him Chief Executive (Leader) and ultimately the President, he found the repercussions of the Kargil incursions complicated his life immensely, probably for the duration of his tenure as President.

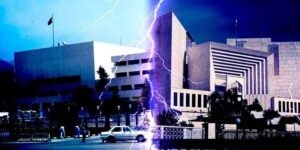

Thinking about this after I finished that article and sent it off, I realized that writing about Musharraf automatically brings up the even larger subject of hybrid military/civilian government itself. I had not mentioned the question that hangs over the whole idea of a Pakistani state—whether a hybrid state can be successful as a democracy or only as an autocracy; really the question is whether states governed by two distinct power centers can be successful at all.

There are complicated issues of political science involved in these questions which I dare not venture into for fear of embarrassing myself. But I believe Pakistan’s “hybrid” system is almost unique. It has been a slow by steady evolution from a political system dominated by the military from the time of Ayub Khan in 1958 to a current system in which the two power centers, the military and civil society share power. They do not share it equally yet, the military still has the guns, they still have veto power over security and international issues, but it looks to me as if the civilians have gained significant power.

So, the question for us is what effect has the fact of Pakistan’s hybrid political setup itself affected Pakistan’s political development. Pakistan is generally acknowledged by political scientists and other experts as a weak state. Readers will know the characteristics of a weak state better than I do as they are the victims of the Pakistani state’s weakness. In general, the primary characteristic of weakness is lack of control over a country’s entire territory (another way of putting this is whether the state has a monopoly on violence). The secondarily criteria are the ability to protect its citizens, to provide law and order, to provide justice, and to provide other public goods (commodities or services that benefit all members of society at no or reduced cost, e.g. health care, education). The provision of public goods varies widely among states depending partly on their economic conditions.

It is not clear why some states are strong, and some are weak, but the explanation surely lies in social and cultural factors which intertwine with the ways that the institutions of the state were created and have evolved over time. In Pakistan, this would involve the military, an institution of great importance in the evolution of the Pakistani state. In this context, there is a strong argument that the military, by its grip on government, has played an important role in making the state weaker. Historically, the Pakistan military has used Pakistan’s geography, its geostrategic location, and the existential threat of its contiguous position next to a hostile India as the reason for its insistence on sharing power with civil society, or at times (3 times actually) wielding it itself. And in either case, it has asserted its strategic need for the lion’s share of domestic resources and at the same time resisted the fundamental economic reform necessary if Pakistan is ever to have a viable economy as well as retarded the social modernisation and reform necessary to make society more equitable.

If serving members of the military read this, they may protest that the military has now modernised its thinking and does not oppose political and economic reform. That may be so, although I am not sure that is true across the spectrum of political and economic issues that confront Pakistan these days, in particular the military’s view of its budgetary needs. But in this article, I am addressing the entire history of military governance in Pakistan, solely and in tandem with civilians, since 1947.

The most flagrant aspect of Pakistan’s weakness as a state is its failure to control its territory and protect its citizens, including those in the military, by maintaining a monopoly of violence. This is the bedrock definition of a strong state. This is indisputable given the 40-year insurgency in Balochistan, the decades-long war against both the Pakistani Taliban, but also against the Afghan Taliban, which were once Pakistan’s proxies, and the plethora of armed militant groups throughout the country whose political and social agenda were, and still are in many cases, in direct contrast to the government’s agenda. Historically, the Pakistani state has fallen short in many other measurements of strength over most of its existence. These public goods include law and order, justice, health services, public education, the social and political advancement of women.

I have not lived in Pakistan for over 20 years, and my pre-pandemic habit of biennial visits has ben curtailed by that pandemic and by age. Much of what I wrote above is very much like I would have written 20 years ago. I realize that things have changed in ways many ways. There are lights that flicker at the end of the tunnel: signs that the military mindset is beginning to change with regard its India-centricity and its strategy to use Pakistan’s geo strategic significance to advance its own ends; signs that the public is holding the military in much lower regard than in the past. But I do not get the impression that things are radically different or radically better, that the Pakistani state is, overall, much stronger or has advanced fundamentally in the past 20 years. I had thought until recently that democracy in the abstract was stronger, but politics seems not to have advanced at all from its zero-sum-game nature of earlier decades.

A timeline that includes endless political crises which seem almost existential and endless economic crises that always threaten international default does not imply any gain in the state’s strength over the last decades. Are we to infer failure of the state by this narrative? What we can infer, I think, is that the political system is not working, that having two competing power centers does not promote state strength.

Pakistan has fooled itself three times already by thinking direct military rule was the answer, and it was not.

The title is a quote from Abraham Lincoln in 1858, delivered during one of his celebrated debates with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas; debates which brought him to the President’s office in Washington two years later just as the American Civil War was beginning.