Bengal without the prefix tries to invent a wholly-contained make-believe identity.

The West Bengal state Cabinet has decided to drop West from the state’s official name and make it either Bongo or Bangla (and Bengal in English).

The trigger for this renaming is the long-time problem that West Bengal faces at meetings convened by the Union government where states get to speak according to the order in which their names appear in the English alphabet. Because of this rule, West Bengal comes last in the list of 29 states and often doesn’t get enough time to speak, or an audience. For instance, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee was cut short as the last speaker at the inter-state council meeting held last month.

It is extremely unfortunate that such a momentous decision was provoked by a reason so bureaucratic. To mitigate this old problem, the newly elected Trinamool Congress had decided to change the state’s official name to Paschim Banga, the Bangla version of West Bengal, after a debate in the media and consultation among political parties and civil society.

But, for unknown reasons, New Delhi never approved the new name.

This time, no such consultation or debate happened before the Cabinet decision to delete West from the state’s name was made. A special session of the Assembly will finally pass that decision.

West Bengal’s Parliamentary Affairs Minister Partha Chatterjee said that the change is for the sake of our “heritage and culture”.

Ironically, writer Nabanita Deb counters exactly that when she said: “The term West Bengal is our history, our heritage. How can we erase that?”

Desh of Bangla speaking people

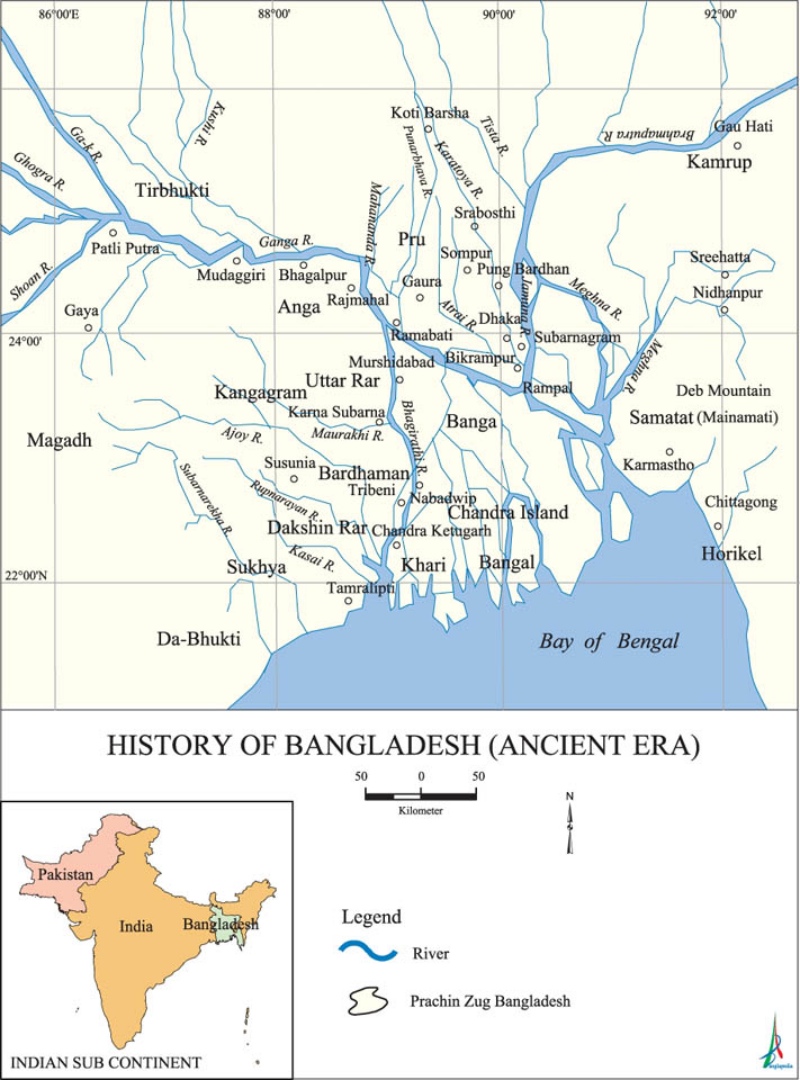

Since 1947, the term West Bengal has also come to mean what we are. It is at least a term rooted in the real past as opposed to one of the proposed alternatives called Banga. The historical kingdom called Banga from where the term originates is wholly outside the borders of West Bengal, largely in the Faridpur-Magura-Shariatpur-Dhaka areas in the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

The western part of Bengal has not been a historically continuous political unit, except since 1947 when Bengal was divided to form the Hindu majority western half called West Bengal and the Muslim majority eastern half called East Bengal. In 1955, East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan, and then after the national liberation struggle, was politically constituted as the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Interestingly, Bangladesh as a name for the whole of Bengal, and also for either part of Bengal, was a name that was in wide currency till 1971 when the sovereign nation-state came to own the name Bangladesh while many people of West Bengal (except a few holdouts, the present author included) slowly gave up that name when they referred to themselves in common parlance, even as it continued to be the western part of historical Bangladesh – the desh, or land, of Bangla speaking people. That historical ethno-linguistic reality of Bangladesh is as true now as it was a couple of hundred years ago.

Bengal is the historical homeland of more than 250 million Bangla speaking people – who represent nearly 1 in 25 human beings in the world and live in the most densely population contiguous stretch on earth. This is no ordinary land. Between the Himalayas and the Bay of Bengal, this land of active rivers teems with life. Survival is a daily epic on this great fragile delta through whose ongoing formation and sustenance, creation intended magic, anger, dreams and struggle.

As Aime Cesaire might say, “a fantastic land, of extraordinary birth, its worth more than any big bang”.

Cleaving into two

The tragic Partition politically divided this land like nothing before. The West is a reminder of what happened, of short-sightedness, of anger, of betrayal, of a cataclysmic event of almost cosmic rage channelized through human agents.

For some, it’s a painful memory that is best forgotten by deletion, for some a painful memory to be reflected upon, for some a historical cross-roads, for some the womb of future dreams, possibly permanently deferred.

To dismiss that memory, however irrelevant it might be to the present populace whose historical memory was distorted by official post-1947 foundational myths, is to deny a people a way of expressing its identity, and to treat the present as being disconnected from the past.

West Bengal without the prefix West tries to invent a wholly-contained make-believe identity limited within its physical territory, as if another cosmic creation of Bengal happened at Partition. This make-believe identity is especially paradoxical for the West whose primarily Hindu, roll-call from Bengal’s glorious past has no East but has Satyendranath Bose’s professorship at Dhaka University, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s deputy-collectorship at Jessore, Rabindranath Tagore’s literary productions while lounging in Kushtia, Shurjo Sen’s armed insurrection in Chittagong. Events, ideas and conceptions get projected schizophrenically within Bengal’s western sliver.

This psychological phenomenon – where trans-frontier locales get uprooted from their real location but are not quite embedded on the other side of the frontier, thus leaving places, faces, spaces, events in a strange purgatory of cognitive inaccessibility – is a major consequence of Partition, giving rise to misshapen, constricted visions of one’s cultural past, severely restricting engagements in the present.

Dropping West will add to this smugness of being complete. But it’s not.

Identity and the West

We, in West Bengal, need the West to avoid losing a sense of our grandmother’s world, losing parts of ourselves, losing our idea of us as a people. There might be no return to the east. There will only be a long march to Delhi, to become a people without grandparents but with an ancient history – true Indians who are nothing but Indians.

One-size-fits-all Indianness, however sophisticated a shoe, has no place for those of us with oddly shaped feet – shapes inherited from places where they don’t fly the tricolour.

The erasure of West further forecloses our possibilities of engaging not in some irredentist dream, but of coming to terms with what in a communally-dominant body politic of Bengal did, and can, go horribly wrong. We now need the reminder of West more then ever as a reminder of the questions: How did we come to be the way we are, and where do we go from here?

[This article is published with the consent of the author. It first appeared in Scroll.in. The author blogs at Hajarduhari]