What happens when the ground beneath your feet sinks, and the roof over your head falls apart? CNA programme Insight looks at the confluence of factors behind a disaster in the Himalayas and what is being done for its mountainfolk.

UTTARAKHAND, India: It was a start to the year that Anjali Rawat and her family did not expect: Having to run for their lives in the middle of the night.

Cracks were appearing in the hotel behind their home in Joshimath town. The hotel windows were falling, an employee informed Anjali’s neighbour.

Months back, cracks had also formed in her home. When her family returned in the morning after they had been forced into the freezing cold, their house “looked the same, but the cracks had increased”, she described.

We heard loud noises, as if an earthquake had struck. But we didn’t know whether our house would break or sink.”

Next, their balcony collapsed, and one side of the house was “wholly damaged”. They had to move into a temporary shelter provided by the municipal authorities.

What happened in the Himalayan town of Joshimath, in India’s northern Uttarakhand state, was not an earthquake but the earth subsiding.

The disaster hit the world headlines as cracks appeared in over 800 buildings, causing many to become unsafe. Some 300 families were forced to evacuate.

Nearly seven months later, residents of the pilgrim town remain unsettled and uncertain about the future — and they are not the only ones, the programme Insight found. The authorities, meanwhile, say they are taking all steps needed to stabilise the hilly areas.

WATCH: After Joshimath’s Collapse, What Will Happen To The People Of India’s Mountain Towns? (46:31)

‘VERY, VERY UNSTABLE’

Scientists believe a confluence of factors caused Joshimath to crumble: unstable ground, unfettered urbanisation including a lack of drainage, and the increased presence of water in part due to climate change.

Joshimath’s popularity with hikers and pilgrims has led to population growth over the decades, from about 48,000 in 2011 to more than 60,000 now.

Situated at an elevation of about 1,900 metres, it is a stop along the way to Badrinath Temple, one of four revered Hindu shrines. The pilgrimage season, which draws millions of devotees, usually lasts for about six months from April.

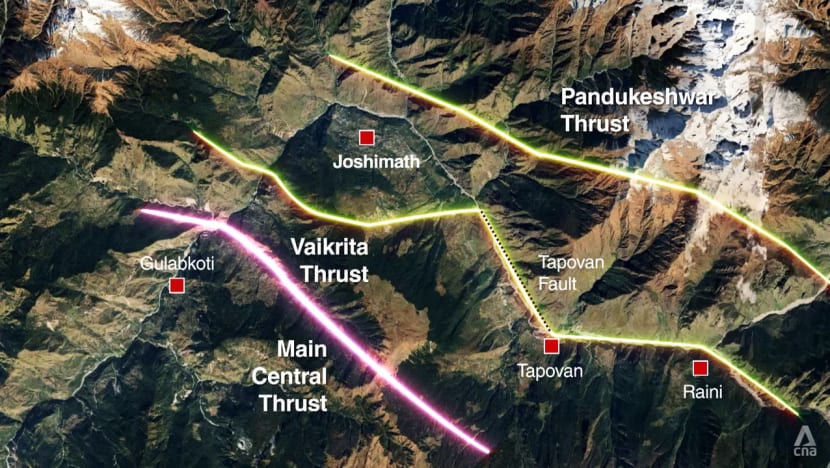

The Himalayan range sits atop fault lines, and Joshimath is built on layers of debris left by glaciers and landslides. In the summer, water is released when glaciers melt.

“Because of the impact of global warming, summer is extending, and winter is shrinking. Snowfall is less, glacial melt is more,” said glaciologist D P Dobhal, a former senior scientist at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology in Uttarakhand’s capital, Dehradun.

Also, when drains are not lined, used water from households and businesses percolates into fissures in the ground. This saturates the soil and makes it “very, very unstable”, said Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology scientist Swapnamita C Vaideswaran.

“There are hotels, (and) all that water is going into the soil. Where’s that water going? How many (sewage) treatment plants are connected?”

About 270 kilometres south, the town of Nainital is similarly vulnerable. Built around a picturesque lake from which a stream called the Balia Nala flows, Nainital has experienced landslides since 1867, including one last year.

“During the last landslide, they shifted 50 families to a school,” said municipal supervisor Rajesh Kshetarya.

Residents such as Rajesh are filled with worry during the rainy season each year. It can rain continuously for two days, he said.

After previous landslides, his family had moved uphill. But cracks appeared in his new home. “We aren’t safe here,” he said. “This area will be in danger if an earthquake strikes. We can’t trust this place where we’re sitting now.”

.JPG?itok=6wgb5yEX)