Turkey is biting the hand that feeds its fragile economy as concern about the nation’s current account deficit heightens.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government says that Europe can’t do without Turkey – a claim repeated by his foreign minister in a column for the U.K. Daily Telegraph on Friday. But the reality is, Turkey is overplaying its hand and needs Europe far more.

Erdoğan levelled tirades of criticism at Europe’s leaders throughout last year, including accusations of Nazi tendencies for Germany and the Netherlands. But Europe is the biggest investor in his country’s economy just when he needs the money the most.

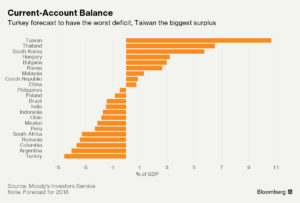

Horrific trade figures published on Monday showed Turkey’s deficit with the rest of the world – the difference between imports and exports – more than doubling in January from a year ago to $9 billion. The figure prompted Asia Unhedged, which analyses market and economic trends, to warn that the situation had become unmanageable and to question why the lira hadn’t already tanked.

Turkey’s widening trade imbalance, exacerbated by Erdoğan’s stimulation of the economy via cheap loans and tax cuts, is the main cause of Turkey’s widening current account deficit, sucking in imported consumer goods and production materials.

The shortfall in the current account needs to be financed by inflows of foreign capital to avoid a sudden correction in the lira and an ensuing economic recession. All this comes as Erdoğan faces re-election – a win he needs to introduce a full presidential system of government approved in a disputed public referendum last year.

Turkey’s economy is running on fumes, in other words, overheating. Foreign direct investment is in decline and hence Turkey is now largely reliant on short-term and fickle portfolio inflows — in the form of foreign purchases of stocks and bonds – to keep growth intact and prevent a run on the lira.

A political crisis with the United States helped provoke a slump in FDI from across the Atlantic to $171 million in 2017, half the $338 million of the previous year. U.S. investment in Turkey had peaked at $4.2 billion in 2007.

That has left Europe as the main source of much-needed funds for Turkey’s imbalanced economy – the continent provided $5 billion last year, more than two-thirds of total inflows of $7.4 billion.

Hence Erdoğan’s attempted rapprochement toward the European Union since the start of 2017.

Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavuşoğlu wrote in the Daily Telegraph – possibly an ill-conceived choice seeing as the paper trumpets Britain’s departure from Europe and imposes a paywall on most content — that Turkey’s EU membership “is to everyone’s benefit, and the pace is controlled not by Turkey but by the EU.”

Under the headline ‘Time to Bust the Myths about Turkey. Europe Couldn’t do without us” Çavuşoğlu went on to say that without Turkey, Europe would be left exposed and vulnerable and that Turkey will be an asset “thanks to an economy that is growing at levels that any European country would love to emulate.”

But Turkey’s renewed and somewhat contrived interest in reinvigorating relations with the EU has been met rather coolly by Europe’s leaders.

In January, during a visit by Erdoğan to Paris, French President Emmanuel Macron stated bluntly that it was time to end the hypocrisy of pretending that Turkey’s membership talks with the EU could be advanced, citing its deteriorating human rights record since Erdoğan introduced a state of emergency after a failed coup in July 2016.

On Thursday, European human rights commissioner Nils Muiznieks told reporters that a refugee deal between the EU and Turkey, which Erdoğan has used as a bargaining chip in relations with Brussels, is now virtually obsolete. Countries have put up so much security along the route and conditions at camps in Greece are so bad that most migrants are deterred from making the trip, he said.

But rather than pursue other means to strengthen bonds between Ankara and Brussels, such as an enhanced Customs Union that would clearly benefit Turkey’s economy and boost investment, Erdoğan is insisting that he will accept nothing less than full membership.

Meanwhile, relations with Turkey’s closest allies of late — Russia and Qatar – have done little to help the government address prime weaknesses in its economy. Much of the high-value business Turkey does in both countries are in the construction industry. Most of the materials used for such projects are locally sourced.

And Russian companies invested a total of just $4 million in Turkey last year — $2 million in October and $2 million in November, central bank data for the current account deficit showed.

Inflows of Qatari investment totaled $100 million in 2017, sliding from $420 million in 2016. That’s one-eighteenth of the $1.8 billion of capital invested by the Netherlands, the country that contributes most to financing Turkey’s trade shortfall. Spain invested $1.45 billion, largely because one of its banks – BBVA — increased its stake in Garanti Bank, a top Turkish lender.

Erdoğan’s apparent love affair with Africa is also bringing little return in terms of trade – Turkey had a marginal surplus with the continent in January. Furthermore, companies from Africa invested just $43 million in Turkey in 2017, with $41 million of that coming from Mauritius. The remaining $2 million was invested by firms from Egypt, with whom Erdoğan has no diplomatic relations since he cut them off in 2013 when Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi was ousted from the Egyptian presidency.

Erdoğan is also doing the country no favours by seeking to ramp up tensions with Greece over territorial rights to islands in the Aegean Sea and gas resources off ethnically-divided Cyprus.

In December, on the eve of a visit to Athens that was trumpeted by the Turkish media as a landmark in relations, Erdoğan almost inexplicably brought up the demarcation of borders in the Aegean under post-World War I treaties, saying they should be re-negotiated. After receiving a swift rebuff from Greece, military tensions in the disputed waters off Turkey’s western coastline have ramped up – a Turkish patrol boat rammed a Greek coastguard ship on Feb. 12 as vessels from both sides encircled a set of disputed islets. Last week, Turkey arrested two Greek soldiers who had wandered across its northwestern border accusing them of espionage.

Greece, still suffering from an economic malaise, invested $0 in Turkey last year. But it wasn’t long ago that its companies were pouring capital into the country. In 2007, they invested $2.4 billion.

The political tensions with Athens — Turkey has also blockaded exploration by EU member Cyprus of gas in the Mediterranean -– have wider consequences for relations with Europe and, consequently, European business perceptions of Turkey. None of this is good news for the Turkish economy.

Turkey’s trade deficit is now an annualized 12.5 percent of GDP. In the absence of the political will to take steps to slow the economy – it grew more than 11 percent annually in the third quarter thanks to Erdoğan’s stimulus measures — such as interest rate hikes, the situation looks unsustainable.

As Asia Unhedged pointed out, the Greek trade deficit was 8 percent of GDP before the country’s collapse in 2009. While Turkey’s economy is inherently stronger than Greece’s was a decade ago, Erdoğan needs to take serious steps to re-embrace Europe and repair the country’s image on the continent. But a significant uptick in investment is highly unlikely unless relations strengthen markedly and quickly. That would require Erdoğan to put a quick stop to Turkey’s descent into authoritarianism, including the state of emergency, something he is unwilling to do.

Turkey’s predicament appears all the worse as the U.S. Federal Reserve and European Central Bank prepared to unwind monetary stimulus. The measures, due this year, are set to suck a considerable amount of capital out of emerging market stocks and bonds and into U.S. and European treasuries.