41 Great Russell Street • London WC1B 3PL

ISBN-13: 978-1849046237

ISBN-10: 1849046239

Paperback

May 2016 • £12.99

9781849046237 • 256pp

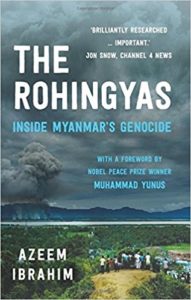

The scale and nature of the violence unleashed by the Myanmar authorities against the Rohingya have prompted a top United Nations official to describe the operation as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” Human Rights Watch has concurred, and Amnesty International has called for an investigation into these criminal acts. The violence, underpinned by the clear intent to eradicate the distinct identity of an ethnic group, meets the criteria under the UN’s Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The issue is no longer internal but international. It demands direct and immediate intervention by the international community.

The military’s ongoing “clearance operation” began in late August of 2017 with the supposed aim of ridding Myanmar of a recently emerged militant group. But this campaign’s real intent is now widely regarded as being to force the ethnic Rohingya, a Muslim minority, from their homes, away from their land, and out of Myanmar. Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, has used tactics that are brutal, indiscriminate, and yet sadly familiar to the Rohingya and other groups in Myanmar such as the ethnic Kachin and Karen.

The Tatmadaw soldiers fired weapons and killed people inside wooden homes, arrested young men, raped women, told residents to leave, and then burned homes to prevent the residents’ return. Myanmar’s Rakhine State, where the Rohingya have mostly lived, remains locked down by the Tatmadaw, blocking media and humanitarian access. But NGO Human Rights Watch has released satellite images showing almost 300 Rohingya villages razed.

These questions are tackled in the revised edition of Azeem Ibrahim’s book, first published in 2016. He argues that Rohingya tragedy has been unfolding for many decades starting with 1948 when Burma got independent. Like 1994 Hutu-Tutsi killings during the Rwanda crisis, how the massacre of 800,000 Rwandans came to pass, Ibrahim explains the reasons behind marginalization of the Rohingyas.

Who are Rohingyas?

Rohingyas are Bengalis from Arakan, which is their ancestral home for more than a thousand years. Arakan and the Rohingyas are inseparable from Bangladesh and Bengalis, and Bangladesh just can’t be a dumping ground for persecuted and expropriated Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.” Unfortunately, what we hear from the Bangladesh Government, media, and a tiny minority of Bangladeshi intellectuals is all about asking (rather requesting) Myanmar to take back Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh; and to treat its Rohingya minority humanely. Some Bangladeshi Muslims and Islamic organizations occasionally protest the killing and persecution of Rohingyas in Myanmar, seemingly only because the victims are Muslims.

Arakan was a Bengali-speaking Muslim kingdom up to 1784 when Buddhist Barmans annexed the kingdom to what is Myanmar today. The British occupied Myanmar or Burma in 1826 and ruled the country up to 1948. When the British left, Arakan, also called Rakhine, remained a part of Myanmar. Meanwhile, thanks to Myanmar government policy, Buddhist/Barman people had outnumbered the indigenous Bengali Rohingyas in Arakan. After 1948, Arakanese Muslims (Bengalis who speak Chittagonian dialect) tried to become independent, in vain. The rest is history.

State violence against the Rohingya goes back decades, but the current anti-Muslim violence can be traced from June 2012, during the country’s democratic transition, when some 200 Rohingya were killed, and over 100,000 were confined to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps. By 2014, over 400,000 had fled to Bangladesh. The issue had been festering for years and stemmed from the fact the Rohingya are not listed as one of the country’s 135 legally-recognized ethnic groups, despite evidence they have lived in the country for generations. The military government stripped them of their citizenship rights in 1982 and has since referred to them as illegal “Bengali” immigrants.

It is interesting to note the roles the neighboring countries have taken. Indian PM Narendra Modi’s visit to Burma immediately after the August crackdown was to assure Aung San Suu Kyi India’s full support for her and Myanmar; as a part of India’s look east policy. India is heavily involved in the development projects in Rakhine and especially in the areas where the Rohingyas are being evicted. Thailand recently honored Myanmar’s Military Chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing with a Medal “Knight Grand Cross (First Class) of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant.” Due to vital economic investments and also it’s connection with the military, China has remained quiet on the issue and used her voting power in the Security Council to favor Myanmar. All these countries have vital investments in Myanmar. The major powers are not providing real help to avert this genocide.

The Rohingya are quite simply one of the most helpless and forsaken peoples of the world. An ethnic minority disdained by the Burmese public and ignored by the Burmese government; the Rohingya do not have full citizenship rights. About 1.1 million Rohingya live in apartheid-like conditions in northern Rakhine. They need to seek official permission to marry or even travel outside their villages. Despite the fact that the vast majority of Rohingya families have called Rakhine home for generations, the government views them as “Bengali” interlopers from across the border. Bangladeshi authorities, meanwhile, have struggled to cope with the influx, frequently turn away Rohingya civilians seeking entry and do not view them as formal refugees.

Aung San Suu Kyi—the leader of the country’s the National League for Democracy (NLD) only cares about her domestic political support that emanates from almost entirely from the ethnically Burman community, who are mainly Buddhists. Inter-communal violence in Myanmar is not simply a predictable side-effect of the country’s difficult transition from authoritarian military rule to democracy. Theravada Buddhism as practiced in Myanmar played an important role in the inter-communal violence. It has been consciously employed by the Myanmar military and the religious actors like the Buddhist monks, to create a nationalist discourse which excludes people of other belief.

An armed movement, the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO), was active in the mid-1980s to 1990s. The RSO did little militarily, but its ties to the Jamaat-e-Islami and Harkat-ul-Jihad-al Islami in Bangladesh and Pakistan caused concern. The RSO had limited ties to al-Qaeda and affiliated charities. Indeed, al-Qaeda’s top representative in Southeast Asia at the time was in the process of bringing the RSO into an umbrella grouping with Jemaah Islamiyah and other groups, known as the Rabitatul Mujahidin. The proliferation of armed training camps compelled Bangladeshi security forces to move against them. By the mid-2000s, the RSO was defunct, but a convenient enough myth for the government to justify its abusive policies.

The Rohingya had hoped that the country’s democratic transition would address their legal rights. Democratic freedoms also unleashed extreme Buddhist nationalism. An active campaign of ethnic cleansing was underway in 2013 (Human Rights Watch, April 22, 2013). Despite a massive exodus of people between 2012 and 2015 — some 112,000 people fled — the conflict was allowed to fester with little international attention. A February 2017 UN report that documented “mass gang-rape, killings – including of babies and young children, brutal beatings, disappearances and other serious human rights violations by Myanmar’s security forces” elicited little outcry (OHCR, February 3).

Ibrahim argues political dynamics is central towards understanding why Rohingyas have been a target of continued persecution and why there is a conspicuous absence of international action. The conventional view is that Myanmar is an isolated state governed by a powerful military who are deeply suspicious of external powers. While cognizant of foreign investment in the country, the military has been opening up to international trade links and a calculated decision regarding Myanmar’s approach to international relations.

Ibrahim’s analysis how exclusionary citizenship laws bear relevance to a broader political-legal question, how legal machinery of a state can be utilized to achieve broader political objectives is helpful to political scientists and legal scholars. He was brief in describing how the impending genocide of the Rohingyas is comparable to the past genocides in Armenia, Germany, and Rwanda, it nevertheless invites more research from the scholars of genocide studies, to be conducted in connection with the Rohingyas.

Regarding the current inaction in the domestic and international fronts, he suggests increasing international pressure on the military regime from multiple fronts; refer past violence to the International Criminal Court (ICC); and finally, intensify pressure on the domestic front. This vision raises several questions; all of which remains unexplained in the book. Ibrahim identifies four key external actors – the United Nations (UN), the US, China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – as having a role to play in increasing political pressure on the military regime for its treatment of the Rohingyas. He has not analyzed the political feasibility of the nature of the pressure; suspension of trade links, international condemnation or outright international intervention. Even though Myanmar is not a signatory of the ICC, Ibrahim vaguely suggests that ICC should commence an investigation into the Rohingya issue. Legal experts will point out; the ICC requires the identification of perpetrators. Are these the key members of the ruling regime, The 969 Buddhist extremist monks or a combination of both? Despite all these questions, the book brings the Rohingya issue to the spotlight of the international community which begs their urgent action.