Remembering Indian Republic Day

Introduction

With a salute of 21 guns and the unfurling of the Indian national flag by Dr. Rajendra Prasad heralded the historic birth of the Indian Republic on January 26, 1950. The transition of India from a British colony to a sovereign, secular and democratic nation was indeed historical, and its journey started around two decades ago with the conceptualisation of the dream in 1930 to its actual realization in 1950. The seeds of a republican nation were sowed at the Lahore session of the Indian National Congress at the midnight of 31st December 1929. The session was held under the Presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru, and those present at the meeting took a pledge to mark January 26 as ‘Independence Day’ to march towards realizing the dream of complete independence from the British. It was also decided that January 26, 1930, would be observed as the Purna Swaraj (Complete Independence) Day. India achieved independence from British rule on 15 August 1947 following the Indian independence movement noted for largely peaceful nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience led by the Indian National Congress, but Vital to India’s self-image as an independent nation was its constitution, completed in 1950, which put in place a sovereign, secular, and democratic republic. After many deliberations and some modifications, the 308 members of the Constituent Assembly signed two hand-written copies of the document, one each in Hindi and English on 24 January 1950. Two days later, it came into effect throughout the nation.

Source: Karthik Navayan – WordPress.com

Role of Leaders

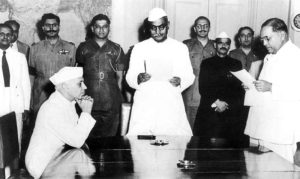

On this day India became a totally republican unit, and it finally realized the dream of Mahatma Gandhi and many freedom fighters who, fought for and sacrificed their lives for the independence of their country. Two days earlier on 24 January 1950, the Secretary of the Constituent Assembly, H.V.R. leugar, who was also the Returning Officer of the election of President of India, declared in the Assembly that Dr. Rajendra Prasad was duly elected to the office under sub-rule (1) of rule 8 of the Rules for the Election of the President. Among others, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel congratulated Dr. Prasad on the great honor conferred on him and said that he had been elected as the Head of the State by the unanimous will of the representatives of the nation. However, speaking of the solemnity of the occasion and heavy responsibility placed on him, Dr. Prasad remarked, ‘I have always held the time for congratulation is not when a man is appointed to an office, but when he retires, and I would like to wait until the moment comes when I have to lay down the office which you have conferred on me to see whether I have deserved the confidence and the goodwill which have been showered on me from all sides and by all friends alike (Kashyap, 2008).

In fact, while Nehru and Prasad had always had the highest personal regard and affection for each other, the two had somewhat different intellectual and ideological orientation. Nehru was a Harrow-Cambridge educated Western-oriented modern liberal. On the other hand, Prasad even though a brilliant scholar, was deeply rooted in the Indian soil. He was a religious-minded person with a healthy conservative approach to life. He represented all that was best in the traditional Indian culture and ethos as Dr. Radhakrishnan once said he was, ‘the suffering servant of India…who incarnates the spirit for which the country stands.’ The sharp difference between Nehru and Prasad surfaced in coming years after the Republic began its journey. Even Dr. Prasad objected to January 26 being fixed as the day for the Constitution taking effect because he said, it was not an auspicious day. This enraged Nehru who said: ‘National programs cannot be fixed according to astrology, and if people want it, let them elect astrologers to govern the country. And if they believe in astrology out of ignorance let us combat it. Despite this, Nehru and Prasad understood each other well. The two had been comrades-in-arms during the national struggle for freedom. Both were prepared to yield, to give and take, to compromise and to cooperate. In the context the thoughts that strike us most compulsively are that Nehru and Prasad were human, all too human, that both in their ways, were great and among the finest of men and patriots, that their differences were not a question of the personal prestige of Prasad or Nehru being at stake but that through these conflicts of views the shape and future of Indian policy was being determined. Having the experiences of the republics of Vaishali and Lichavi and the ideals of Dharma-ruled kings from Vikramaditya to Shivaji, we were ready to move ahead.

Since then every year the date of 26 January is celebrated as the Republic Day with patriotic fervor of the people and is one of the three national holidays in India. It marked the true spirit of Independence and by applying the Constitution gave the citizens of India the power to govern themselves by choosing their government. After being declared Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India took oath at the Durbar Hall in the Government House and the Irwin Stadium he unfurled the National Flag. Like the United States of America, India has an elaborate flag code which carries some restrictions. The British are very careless about the way they treat their flag, and so are the Japanese. The French get upset only if their flag is reviled during a public ceremony when the Republic is all dressed up. Sweden and Norway are comfortable about the flag. While Denmark advocates that care is taken so that the flag does not trail on the ground, the German balance their laws against flag desecration with the right to freedom of expression. Ireland has no established norms on how the flag should be treated, but only advises that it should be handled with care and respect (Gupta, 2012). But in India we are different.

Establishment of Republic in India was hailed largely in the country and abroad and Dr. Rajendra Prasad, in his first special message to his countrymen, on the birth of the Indian Republic said, ‘We must re-dedicate ourselves on this day on the peaceful but sure realisation of the dream that had inspired the Father of our Nation and the other captains and soldiers of our freedom struggle, the goal of establishing a classless, cooperative, free and happy society in his country. We must remember that this is more a day of dedications than of rejoicing – dedication to the glorious task of making the peasants and workers the toilers and the thinkers entirely free, happy and cultured’. Likewise C. Rajagopalachari, His Excellency the Governor-General in a broadcast talk from the Delhi Station of All-India Radio on 26 January 1950 said : ‘On the eve of my laying down office, with the inauguration of the Republic, I should like to tender my greetings and best wishes to the men and women of India who will henceforth be a citizen of a republic. I feel deeply thankful for the affection showered on me by all sections of the people which alone enabled me to bear the burden of an office to the duties and conventions of which I had been an utter stranger’.

At the time of the emergence of Indian Republic Sir Anthony Eden, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (April 1955 to January 1957), said, ‘Of all the experiments in government, which have been attempted since the beginning of time, I believe that the Indian venture into Parliamentary government is the most exciting. A vast continent is attempting to apply to its tens and thousands of millions a system of free democracy… It is a brave thing to try to do so. The Indian venture is not a pale imitation of our practice at home, but a magnified and multiplied reproduction on a scale we have never dreamt of. If it succeeds, its influence on Asia is incalculable for good. Whatever the outcome we must honor those who attempt it (Narayan, 2002). A more meaningful opinion was expressed by Granville Austin, an American Constitutional authority, who wrote that what the Indian Constituent Assembly began was ‘perhaps the greatest political venture since that originated in Philadelphia in 1787.’ He also described the Indian Constitution as ‘first and foremost a social document’… ‘The majority of India’s constitutional provisions are either directly arrived at furthering the aim of social revolution or attempt to foster this revolution by establishing conditions necessary for its achievement.’

Real Meaning of Republic

The term ‘Republic’ which India had declared itself to be on 26 January 1950 as a follow-up of the Constitution, derived from the Latin words res publica, public affair or thing. That concept was in turn loosely equivalent to the classical Greek ta koinonia, common things or property; a term initially applied in the early city-state to the city’s treasure, the public funds, and then by analogy coming to symbolize and denote the common interests. It is a term meaning i. A state not ruled by a monarch or emperor, generally a public interest and not a private or hereditary property; ii. A state where power is not directly in the hands of or subject to complete control by the people, in contrast with democracy; iii. More loosely, any regime where government depends actually or nominally on popular will (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1768). During the later middle ages, there were established some brief-lived local republics, consequent on revolt. But it was in individual city-states of Italy that the Republic re-emerged as a meaningful designation and form of government. In modern usage of the republic which derived the dual ideas, the absence of monarchy, and some degree of avowed concern for the common welfare of the state and public control or participation.

The concept of republic witnessed several ups and downs as a result of the changed contexts. As a combined idea of the absence of monarchy, a realm of public affairs and popular consent or participation first emerged, generally as temporary phenomena in the 17th and 18th centuries. Further, during the 19th century, the moral significance of the republican idea declined in Europe, where monarchies continued, and republics remained the exception. Constitutional government spread in the monarchies, and by the early 20th century the term republic no longer connoted the substance and content of political institutions and practice. After World War II, moreover, the term had still less relevance. In essence, the primary classification of government was to constitutional government and dictatorships, a division which corresponded in ethos to the former opposition of republics and monarchy. But gradually contemporary ideas on the issue, Montesquieu, in particular, gave the idea of democracy as linear and small scale and insisted that democracy was impossible in a larger state which, could be at best a representative republic. These and other related were studied and combined by a number of the founding fathers, and especially by James Madison, who used the term republic i. as a technical designation for representative government as opposed to direct democracy and ii. to insist on the necessity for a system of checks and balances against the dangers of straight majoritarian decision in a legislature elected by majority on a single principle of representation. The insistence that republic is not synonymous with democracy either as direct democracy or as simple majoritarian democracy, but rather is compatible constitutional democracy, is correct in the particular US context.

Image credits: Republic-Day-HD-Images-Free-Download-with-flag-taj-mahal, Karthik Navayan – WordPress.com, The Indian Express.com