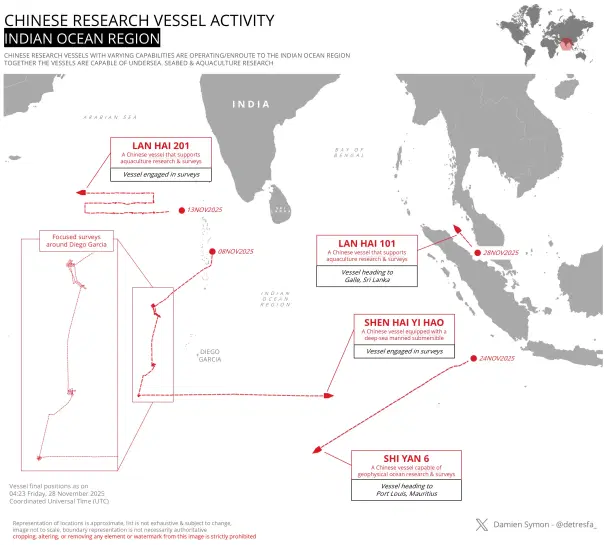

Four Chinese research vessels, all capable of collecting oceanographic, bathymetric, or acoustic data with military value, are now present in or heading toward the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), marking one of the densest clusters of Chinese survey activity in these waters in recent months.

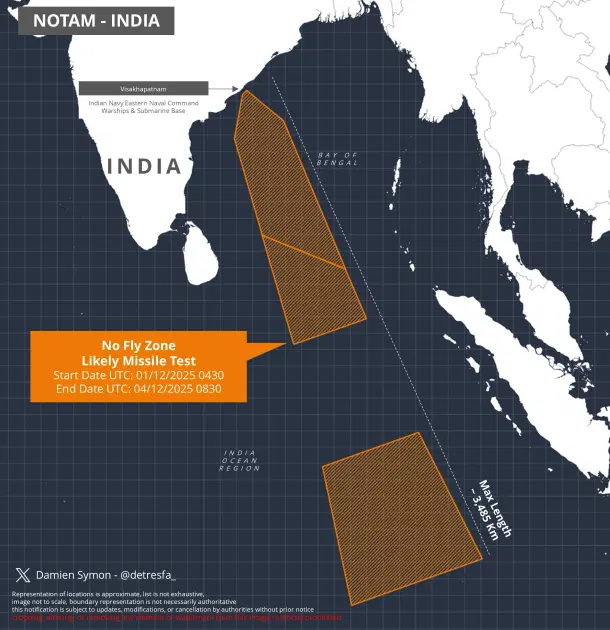

Their presence coincide with India issuing a notification for what appears to be a major missile test between 1 and 4 December 2025, likely a long-range system and possibly even a Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM), though this remains unconfirmed.

The latest entrant to the IOR, Lan Hai 101, is capable of aquaculture research but, like many Chinese dual-use platforms, carries instrumentation that enables wide-area ocean surveys. The vessel is now heading toward Galle in Sri Lanka, a port Beijing-aligned ships have used frequently in the past.

The second vessel, Shi Yan 6, which specialises in geophysical ocean research, is currently moving toward Port Louis, Mauritius, another location that has seen repeated Chinese scientific presence.

Meanwhile, Shen Hai Yi Hao, a ship equipped with a deep-sea manned submersible, has begun survey operations near Southeast Asia and is slowly making its way deeper into the Indian Ocean. The fourth vessel, Lan Hai 201, has already been active near Diego Garcia, where it conducted focused seabed and hydrological surveys earlier this month.

These activities are not unusual in isolation. China regularly deploys survey ships across the Indo-Pacific, but the timing is significant.

India has issued a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) demarcating a massive no-fly zone extending to nearly 3,485 kilometres from the coast of Visakhapatnam, the home of the Eastern Naval Command and India’s nuclear submarines.

The elongated danger zone matches the profile of a long-range ballistic missile test, and its launch point suggests a sea-borne platform may be involved. While New Delhi has not released details, the pattern strongly resembles past NOTAMs issued for K-series SLBM trials.

This is not the first time Beijing has positioned survey vessels in the Indian Ocean during major Indian missile events. In previous years, Chinese ships such as Yuan Wang tracking vessels or Qianlong-class survey ships have been observed lingering in regions aligned with Indian test trajectories. T

hough Beijing frames these deployments as benign scientific missions, their zones of activity often overlap with Indian missile corridors or known areas of strategic naval movement. The pattern suggests deliberate positioning, likely to monitor telemetry, underwater shock signatures, acoustic propagation, and residual debris fields, all of which can yield valuable intelligence.

But Chinese survey operations go beyond missile tracking. The real strategic prize is data, including detailed, high-resolution mapping of the ocean floor, thermoclines, salinity gradients, and acoustic conditions across the IOR. Modern naval warfare, particularly submarine warfare, is an acoustic battle.

Understanding how sound travels through specific water columns enables a navy to hide its own submarines more effectively and detect adversary submarines at longer ranges.

Bathymetric mapping is central to this effort. The contours, ridges, trenches, and sediment composition of the seabed influence how sound waves bend, scatter, or dissipate. Submarines exploit these variations to evade detection by hugging underwater cliffs, diving into sound-absorbing basins, or using thermal layers to mask their signatures.

If China possesses granular, three-dimensional maps of these underwater features, it can model how its own submarines, including the next-generation Type 096 SSBNs, should route themselves for maximum stealth in the IOR.

Conversely, this data is equally useful for tracking adversary submarines.

For example, by knowing where the seabed amplifies low-frequency sound or where sound channels naturally form, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) can position underwater sensors, deploy towed arrays, or route its anti-submarine aircraft to exploit the ocean’s natural acoustics.

Even small survey vessels, operating under the guise of scientific missions, can accumulate enormous volumes of acoustic reference data. Over time, these datasets feed into predictive models that help the PLAN build an acoustic “map” of Indian submarine operations.

Chinese vessels also often lower equipment such as sub-bottom profilers, side-scan sonars, magnetometers, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). These instruments can identify seabed disturbances caused by submarine trails, map potential SLBM recovery zones, or locate deep-sea features that could house future Chinese listening devices.

The Shen Hai Yi Hao, with its manned submersible, adds another layer, the ability to place or retrieve objects at great depth, a capability with obvious intelligence potential.

India has long been aware of these tactics, and its security agencies have repeatedly assessed Chinese oceanographic missions as part of a larger pattern of “pre-positioning.” Beijing is building an oceanographic library of the IOR, one that can underpin PLAN operations as it pushes farther west. This is particularly relevant as China eyes greater access to ports in the region — Gwadar, Hambantota, Kyaukpyu, and now potential footholds in Mauritius and the Maldives.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published