Image captured from YouTube presentation

Image captured from YouTube presentation

Cinema and Politics in India

In India, cinema has never been just entertainment. From the early days of nationalist films in the 1930s to post-independence patriotic blockbusters, Bollywood has often been a vehicle for political narratives. In recent years, however, this relationship has taken on a sharper edge. Filmmakers have increasingly aligned their work with ideological projects, with cinema becoming a battlefield where religious, cultural, and political identities are contested.

While Hollywood too has a long history of war propaganda and political messaging, Bollywood’s present trajectory is distinctive in its alignment with Hindutva politics. Many films now amplify narratives of Hindu victimhood, while portraying Muslims as aggressors, infiltrators, or threats to national unity. At the same time, attempts to portray pluralism, interfaith romance, or dissent have come under boycott threats and political pressure.

The Politics of Boycotts

The boycott culture around Bollywood has intensified since the 2019–2020 protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act. For example, Chhapaak (2020), a film about an acid-attack survivor, was targeted not because of its subject matter but because its lead actress, Deepika Padukone, expressed solidarity with students assaulted at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Since then, filmmakers have avoided subjects that could provoke nationalist outrage—particularly interfaith love stories involving Muslims, derided as “love jihad” by Hindu nationalists.

Meanwhile, films that cater to Hindutva sentiment have thrived. PM Narendra Modi (2019) glorified the Prime Minister’s journey. The Kashmir Files (2021) framed the 1990s exodus of Kashmiri Pandits as Hindu genocide, with graphic violence and one-sided historical retelling. The Kerala Story (2022) suggested mass conversions of Hindu women by Islamist groups. Swatantrya Veer Savarkar (2024) rehabilitated a controversial Hindutva ideologue. These films were aggressively promoted by the BJP ecosystem and benefitted from the surrounding controversy.

Yet boycott calls do not always succeed. Pathaan (2023), starring Shah Rukh Khan, weathered Hindutva campaigns and became a global hit. This suggests that while politics shapes the cultural atmosphere, audiences can still defy the imposed ideological lens.

Revisiting 1946: Direct Action Day and the Calcutta Riots

Against this backdrop comes The Bengal Files, Vivek Agnihotri’s latest project, timed for release just months before the 2026 West Bengal Assembly election. The film revisits one of the darkest chapters of Bengal’s history—the Great Calcutta Killings of August 1946.

The violence began after the All India Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, called for “Direct Action Day” to demand Pakistan. On August 16, mass rallies turned violent. Clashes between Hindus and Muslims spiraled into days of rioting, leaving over 4,000 dead and tens of thousands injured. The killings hardened communal divisions and set the stage for Partition the following year.

While historians debate the responsibility of the League, the British colonial administration, and Hindu groups, Agnihotri’s film appears to frame the episode as a Hindu genocide perpetrated by Muslims. This framing aligns neatly with Hindutva narratives of historical Hindu victimhood at the hands of Muslims—narratives that have been politically weaponized in present-day India.

The “Files” Formula

Agnihotri’s “Files” films follow a clear pattern. Each selects a traumatic historical or political event, emphasizes Hindu suffering, and presents it with a mix of dramatization, selective history, and contemporary political messaging. The films generate controversy, attract mainstream attention, and galvanize nationalist audiences.

The Tashkent Files (2019) questioned the circumstances of Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death, feeding conspiracy theories.

The Kashmir Files (2021) presented a harrowing account of Pandit displacement, widely criticized for its communal slant.

The Bengal Files now deploys the same formula: graphic violence, Hindu victimization, and timing that coincides with an election campaign.

This formula has a dual effect. It boosts box-office revenue by leveraging controversy, and it reinforces the BJP’s political messaging. By aligning cultural memory with electoral strategy, the films act as unofficial campaign material.

The Trailer Controversy

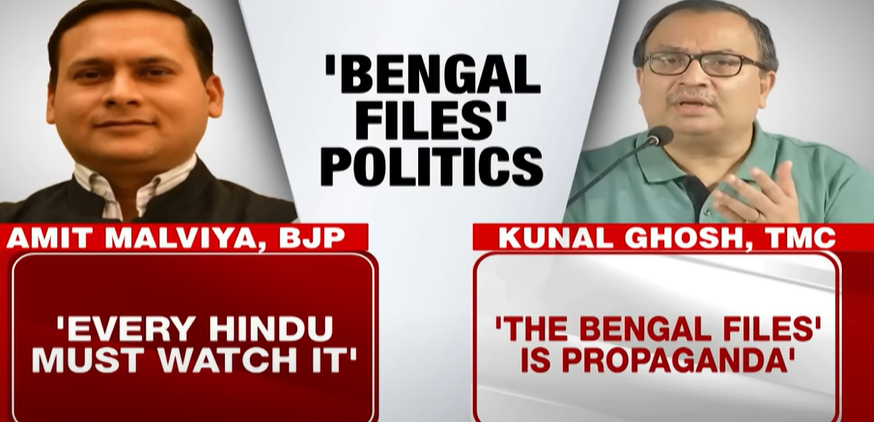

The release of The Bengal Files trailer on August 16, 2025—symbolically timed to the anniversary of Direct Action Day—sparked immediate controversy in Kolkata. Police disrupted the event at a hotel, citing lack of permission. Agnihotri accused the Trinamool Congress (TMC) government of “anarchy” and “dictatorship,” claiming that the state wanted to suppress discussion of demographic change.

His wife, actor Pallavi Joshi, echoed the charge, framing it as a violation of freedom of expression. The TMC countered that the filmmaker’s intent was a “deliberate attempt to malign Bengal” and to stoke communal division ahead of elections.

By blocking the event, the TMC inadvertently amplified the controversy. What might have been a routine trailer launch became a headline-grabbing clash between state power and artistic expression—playing perfectly into Agnihotri’s publicity strategy.

Demographic Anxiety and Electoral Politics

The reference to “demographic change” reveals the deeper political subtext. For years, the BJP has warned of “illegal immigration” from Bangladesh altering Bengal’s demographics, often framing the issue in communal terms. Episodes of violence, such as the April 2025 attack on Hindu residents in Murshidabad, have kept the rhetoric alive.

Agnihotri’s film taps into these anxieties, linking historical trauma with present fears. By portraying Muslims as aggressors in 1946, The Bengal Files implicitly supports the BJP’s narrative of Muslims as a demographic and cultural threat today. In an election where the BJP seeks to expand its presence in Bengal, such a cultural intervention is not accidental.

Freedom of Expression or Political Campaigning?

The controversy also raises questions about censorship and freedom of expression. Should a state government intervene to block a film’s release or trailer launch? In principle, the answer is no. Suppressing art—even politically charged art—feeds into claims of authoritarianism and only strengthens the narrative of victimhood.

At the same time, The Bengal Files is not just a film. It is part of a broader campaign ecosystem where cinema is weaponized for electoral gain. In this sense, it occupies a gray zone between art and propaganda. Freedom of expression should be protected, but the political deployment of cinema must also be recognized for what it is.

Cinema as Cultural Weapon

The rise of politically charged films reflects a larger transformation in Indian cultural politics. Where cinema once offered escapism or nuanced explorations of social issues, it is now increasingly a tool of ideological warfare. The stakes are not just box-office numbers, but the framing of history, the shaping of identity, and the mobilization of voters.

In Bengal, this is especially significant. The state has a long tradition of cultural pluralism and political radicalism. Yet it has also been a site of some of the subcontinent’s bloodiest communal conflicts. Revisiting those conflicts through a Hindutva lens risks reopening wounds rather than healing them.

Conclusion: The Battle for Memory

The Bengal Files is more than a film release; it is an intervention in Bengal’s political battle ahead of 2026. By invoking the horrors of 1946, it seeks to shape how voters think about identity, community, and belonging today. Its controversy illustrates how cinema in India has become a proxy battlefield for politics—one where history is not only remembered but actively rewritten.

The question, then, is not just whether Agnihotri’s film succeeds at the box office. It is whether Indian cinema can remain a space for creative exploration, or whether it will continue to be reduced to an electoral weapon. As long as films like The Bengal Files dominate the cultural conversation, the line between art and propaganda will grow ever thinner, and India’s screens will continue to reflect not just stories, but the nation’s deepest political divides.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published