Publisher: Juggernaut Publication

ISBN: 9789353459871

GTIN: 9789353459871

Author Halder, Deep

Pub Date 01/01/2026

Pages 316 Price ₹499.00

Country of Origin: India

ISBN : 978-9353459871 ; Pages : 316; Paperback

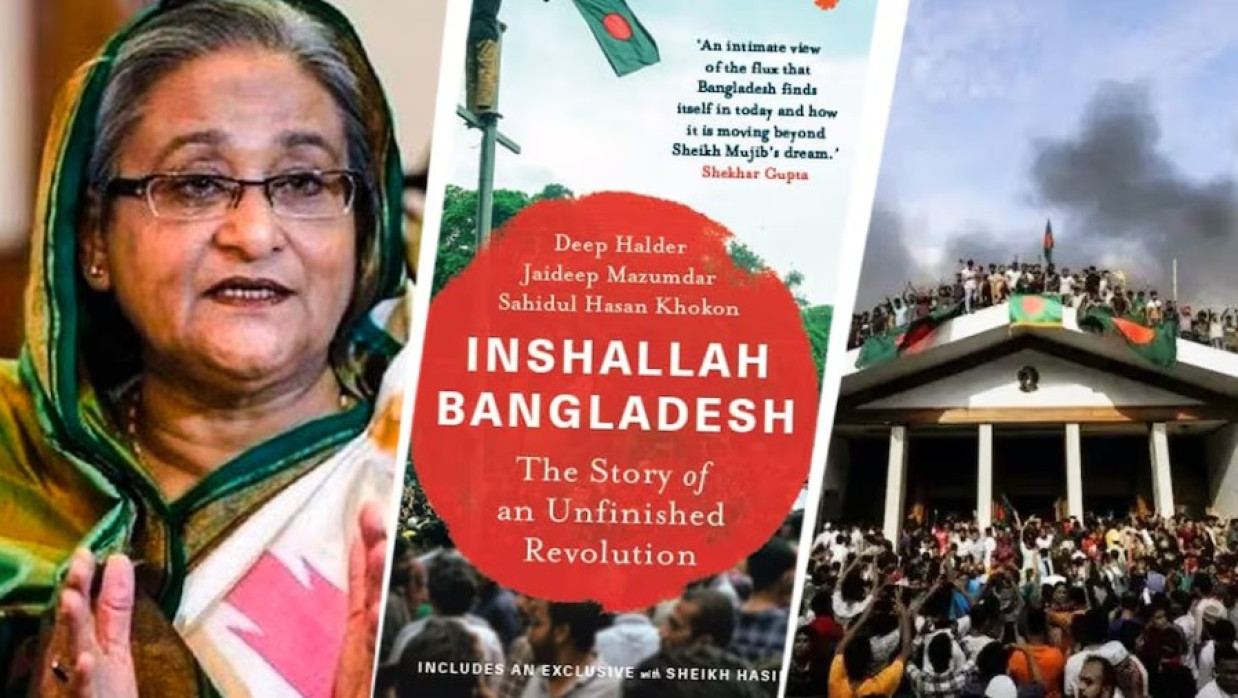

Book Review Essay: Inshallah Bangladesh: A Chronicle of Upheaval with an Unfinished Argument

The Story of an Unfinished Revolution by Deep Halder, Jaideep Mazumdar, and Sahidul Hasan Khokon is an ambitious attempt to recount the events that rocked Bangladesh in 2024. The authors offer what they claim to be “the full chronicle” of the groundswell of protests that eventually upended the 15-year rule of Sheikh Hasina. Tracking the movement’s origins from the student protests against job quotas in Dhaka University to its crescendo as a mass movement against Hasina’s continued rule, the book documents how the “reign of terror” that began in 2009 ultimately came to an end in a surreal, humiliating escape from Dhaka. Drawing from the on-the-ground reporting, eyewitness accounts, and interviews of political leaders, Inshallah Bangladesh attempts to capture a year of unrivalled socio-political upheaval.

In many ways, the authors hit the nail on the head. Bangladesh in 2024 was, and remains, a country teeming with young job-seekers, politically disaffected, weary of dynastic succession, and barely able to hold its own over breakneck demographic growth. Corruption and political violence, coercion and impunity had, by the time of Hasina’s resignation in July 2024, reached levels that could no longer be ignored by the regime’s supporters. The combination of joblessness, an increasingly cynical youth, and the lack of political space to demand accountability created a public tinderbox that only needed a spark. That “spark”, the authors make clear, came in the form of a student movement against quotas that channeled, and added to, a long-standing frustration with an authoritarian, personalistic regime.

In documenting this frustration and the ferment that would finally become an all-consuming revolt against dynastic politics, Inshallah Bangladesh provides an important account of the key events of 2024. The reporting on the flight from the power of Hasina, the confusion at Ganabhaban, her initial decision to resist, then later concede, the pleas of the chiefs of the army and air force, an Indian emissary’s veiled threats, the last-minute dash to the helipad, is told with a narrative flair that many history books about Bangladesh will perhaps never possess. The scenes of rage and chaos in Dhaka in August 2024, the unravelling of the “cult of Hasina” are here, as are the visceral accounts of a public fed up with corruption, repression, and impunity.

At the same time, this focus on drama detracts from a fuller analysis of the socio-political rot, the state-sponsored violence, and years of impunity that, it must be said, created the conditions for this kind of an explosion. The excesses of protesters, the vandalism of public property, attacks on police, and alleged opportunists of the change of regime are detailed in the book. Yet, it is as if they happened in a vacuum and not as a response to enforced disappearances, custodial killings, political trials, impunity, and state-sanctioned violence over the years. It is this absence, or perhaps selective amnesia, that limits the authors’ claim of “full chronicle”.

The most obvious limitation is the framing by Deep Halder, one of the co-authors of this book, which betrays his ongoing faith in India’s civilizational benevolence and role as Bangladesh’s perpetual guardian. His 2018 book, Being Hindu in Bangladesh, is perhaps the most eloquent work on India’s covert role in Bangladesh from its birth to this day. In Inshallah Bangladesh, he and the other co-authors continue to evince the same pro-India bias. It is an India, we are reminded at regular intervals, that has ensured Hasina’s safe exit, offered her personal security, and that singlehandedly seeks to stabilize the teetering country that Sheikh Hasina ran for over a decade.

Halder misses here, or chooses to ignore, the ubiquity of the Indian intelligence establishment in Bangladesh and the penetration of its agencies into the state apparatus during Hasina’s reign. Some Bangladeshis will indeed speak favorably of these institutions and point out that their presence prevented a full-blown civil war or the collapse of the state. What Halder does not register, or at least chooses to elide, is why so many Bangladeshis, from the left to the right, secularists to Islamists, firmly believe that New Delhi effectively owned Dhaka for over a decade, and that it was these preferences, rather than any national interest, that influenced political and electoral outcomes.

Halder misses another opportunity when he inexplicably allows the idea that the revolts and anti-Hasina movement of 2024 were a CIA plot to stand unchallenged in the text, reiterating the words of one former Bangladeshi cabinet minister in the magazine Swarajya that it was “a perfect CIA plot”. The suggestion, by implication, is that Bangladesh is but a chessboard, that foreign powers are responsible for its ups and downs, rather than an actor in its own right. This is doubly ironic because Hasina’s government had used precisely the same language in 2024 in dismissing all criticism, and only in 2024, as an effort at regime change rather than a response to ground realities.

The book’s other blind spot, though not uncharacteristic of such narratives, is its treatment of Bangladesh’s political class and, by extension, of civil society and organized politics. On the one hand, it is all too ready to catalog the excesses of the protesters and sympathizers of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), to harp on the toppling of statues and the violence, coercion, and financial inducements meted out by BNP activists, particularly in rural areas. It does so even while acknowledging, albeit perfunctorily, the abuses committed by the Awami League (AL) and its allies over the past decade.

In particular, Halder notes that policemen were stripped and beaten during the revolt. Still, he omits mention of the innumerable cases of enforced disappearance, extrajudicial killing, and torture reported by civil society groups, media, the United Nations, and human rights groups during the years of AL’s political and electoral dominance. This is not to suggest that these crimes were “excusable” or proportionate to the transgressions of the protesters in 2024. They were neither, and it is telling that the book does not pause to consider why the abuses of a ruling party, even if, as this book shows, they were committed by Hasina’s political opponents as well, were not merely episodic but systemic and, to an extent, institutionalized in Bangladesh over the past decade.

Equally illuminating is the book’s treatment of Dr. Muhammad Yunus. After Hasina’s resignation, it was her accusation that Yunus had met with US President Donald Trump and agreed to engineer her downfall. The book quotes her without comment. In any other setting, this would be a laughable charge, but the authors take this, perhaps unintentionally, as an article of faith and go on to note that Yunus a secularist, nationalist, and a Bangladeshi whose face is inextricably linked to the struggles against military dictatorship and crony capitalism had been, to their surprise, the “wrong opponent” and a potent, effective political symbol for the anti-AL forces.

Halder, however, doesn't stay with this analysis and, to his credit, eventually does a U-turn to note that the return of BNP and the recent elections have created a political vacuum that can be filled by the Islamists, whose electoral gains since 2009 are detailed, albeit without much historical context. The author does not go as far as to declare the coming of Bangladesh’s “Taliban”, but his references to the growing influence of Islamists, their road to power, and how Bangladesh can avoid this “nightmare” will be recognizable to many readers of Indian political journalism on Bangladesh. In fact, the book reinforces a trope that is as old as Bangladeshi scholarship in India: the ever-present fear of Bangladesh’s Talibanization.

The book repeatedly reminds its readers that an upsurge of Islamist forces is a threat not just to Bangladeshi secularists and the middle class but also to Hindu minorities and, most importantly, to New Delhi’s strategic interests. But such warnings and reminders are an incomplete narrative, because the great majority of the Bangladeshis who took to the streets in 2024 were not Islamists, were not working with any foreign power, were not seeking to harm Hindu minorities, and were not working to further India’s interests. These Bangladeshis were acting, as Bangladeshis often have, for reasons that have been unstated or unacknowledged in this book: to demand jobs, accountability, justice, and an end to political repression, and to vent their fury at the dynastic politics that prevented them from having a say in the future of their country.

The authors are also too quick to rely on familiar tropes and worn-out arguments, such as Hindu victimhood, Islamist threat, and Indian kindness, rather than to meaningfully engage with the structural and political roots of Bangladeshi resentment towards India. The passages in this book that focus on the recent controversy over the activities of ISKCON in Bangladesh and the arrest and beating of its activist Chinmoy Krishna Das in Satkhira are an example. The book does not go into the deeper historical or political reasons for Bangladeshis’ wariness of certain transnationalist groups, many of which have strong links to Indian political and strategic establishments. This, too, is an example of the authors’ reluctance to engage with a more political and structural critique of India’s role in Bangladesh.

Inshallah Bangladesh is a riveting read in many ways, and the authors should be commended for an account of tumultuous events that is even-handed when it comes to the problems of the Hasina regime and the post-Hasina transition. It is right to note that Bangladeshis were pushed to a point where Hasina’s excesses were no longer tolerable, and this did, in considerable measure, contribute to the upsurge in violence. The authors' documented frustration with dynastic politics is real. But this does not fully explain the ferocity with which ordinary Bangladeshis, not just activists or opposition figures, rose up in anger against the AL government or the anti-Hasina agitators, and the book offers a less than full account in this regard.

Nor can the anger, popular or elite, be reduced to Islamists, proxies of foreign powers, or opportunistic forces. The protests and the upsurge in violence against the Hasina regime did, as the book acknowledges, happen and could not have been as ferocious without long-term causes. This is one reason it is a stretch to see Bangladesh's revolution as “unfinished”. The book notes that Bangladesh’s democratic transition remains “unsettled,” but fails to mention that this, in itself, is a historical anomaly. No other post-colonial state in Bangladesh’s region and in its geostrategic context has ever made a peaceful transition of power in such a fractious setting.

It is also the authors’ last contribution to what this book, and the literature about Bangladesh produced in India, really is: an effort not at dispassionate understanding or at reciting the complex history of a country and its people but at molding the regional perception of the country and the political changes within it. In using old templates of repeated arguments, it eludes an incomplete, skewed, and, to an extent, inaccurate understanding of Bangladesh, one that is limited by an outsider’s view of Bangladesh and its people, and one that may not survive the full brunt of the country’s democratic transition that the authors write of.

The authors will, in time, be best remembered for their claim to have fully and accurately chronicled the revolutions of 2024: they haven’t. They have, in some ways, provided us with the propaganda narrative that Bangladeshi popular opposition to dynastic politics, mobilized in pursuit of legitimate political grievances, is, in fact, proxy foreign policy. This is why it is up to Bangladeshis, alone, to understand, debate, and defend their own revolution, unfinished as it may be.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published