Peaceful Election, Landslide Mandate, Now the Hard Work Begins

The election Bangladesh just held was, above all else, a turning-point election after the uprising.

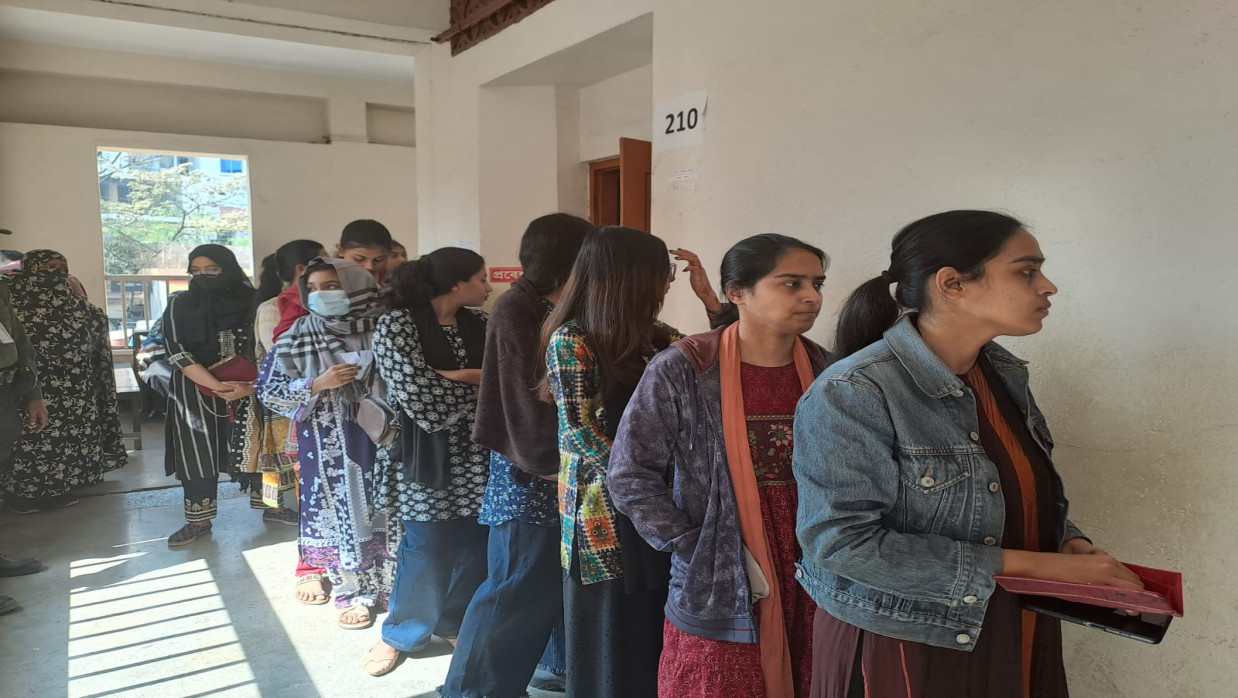

Bangladesh’s 13th parliamentary election on 12 February 2026 was a national exercise held in a largely peaceful atmosphere, following years of fraught balloting and the trauma of the police crackdown and subsequent political rupture of 2024. The election was reported by multiple international outlets to be one of the most credible Bangladesh has seen in decades, with overall turnout estimated at approximately 59–60%.

The headline result was overwhelming. Led by Tarique Rahman, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) won a parliamentary majority with approximately 209–212 seats (exact total to be determined by commission certification and coalition math), and the Jamaat-e-Islami–led alliance is set to be the largest opposition grouping.

The historical significance of this election will not be determined by the number of seats won, however. It will be decided by whether the same security forces, Election Commission, and interim government that facilitated a mostly peaceful vote can provide credible remedies where they fell short, and whether the victors can translate a “landslide mandate” into substantive reform, political restraint, and national reconciliation.

Interim government’s legitimacy at stake

While the interim government led by Chief Adviser Prof. Muhammad Yunus undoubtedly faces an immense task in shepherding the nation towards reform and supporting a democratic handover of power, it is also at this stage widely credited (by supporters and many previous critics) with returning a baseline of stability and steering the country towards this transfer after an exceptionally tumultuous period of rule. We have seen major media outlets underscore the interim setup’s contribution to providing enough political runway for Bangladesh to not just hold an election, but also an election coupled with a reform agenda.

But make no mistake. The interim government’s biggest responsibility now is backward-looking: how allegations of irregularities are handled in the coming days will be critical to salvaging what remains of the interim administration’s reputation. It matters not just because of short-term politics, but because this election also served as a referendum on the post-2024 transition itself. Should credible doubts about the vote-counting process, the treatment of rejected ballots, or last-minute alterations to unofficial results be allowed to fester, particularly in tightly contested seats, the Interim Government risks tarnishing what has otherwise been touted internationally as a successful transitional handover.

For that reason, the easiest path for the outgoing interim leadership to demonstrate class is not through defensiveness but through institutional confidence: if there are lawful grounds to pursue election complaints, let the petitions proceed, and have the results recounted where justified. Publish clear audits and let voters decide.

Armed forces: restraint visible, influence persistent

There are two roles Bangladesh’s Armed Forces have played during this cycle that must be separated analytically:

- First, as providers of operational security support, facilitating polling station security, logistical groundwork, and public order on election day, and

- Second, as Bangladesh’s political shadow power. The longer historical reality is that even decades into civilian rule, the military remains an influential player.

On election day itself, Bangladesh Army chief Gen. Waker-Uz-Zaman helped set the tone by explicitly encouraging security forces not to act as “partisan soldiers” but to serve neutrally and professionally. This should reassure voters that the Armed Forces upheld their duty to keep Bangladesh safe without overtly swaying the outcome.

On structural questions, we have already seen commentary, including Al Jazeera’s own reporting in the lead-up to polling, that recognizes the reality: coups may be a dormant threat for now, but power politics and the military’s seat at Bangladesh’s elite negotiating table will remain robust for the foreseeable future.

The fact that we have seen a peaceful election result carries one key implication: the Armed Forces fulfilled the role voters needed them to play in this cycle. By some metrics, that stability could be achieved without the Armed Forces themselves engaging in overt political engineering.

If that precedent holds moving forward and the military stays out of partisan political adjudication over disputed seats, the most positive “legacy” the military can claim from this election cycle will be institutional: it has provided necessary security support for the vote without overtly trying to shape the results itself.

The opposite, however, will begin to poison that reputation: should disputed seats be decided secretly, or if political vengeance runs too hot, to deploy security agencies as partisan enforcement arms. Bangladesh’s military will maintain long-term influence whether it likes it or not. Staying out of the political resolution process is the only way to guarantee its reputation abroad and at home.

Election commission: trustworthiness begins after polls close

Credit where credit is due: Bangladesh Election Commission (EC) has undoubtedly earned praise relative to Bangladesh’s recent history for the management of polling day itself.

Speaking after results started coming in, Chief Election Commissioner A. M. M. Nasir Uddin called Saturday’s election “among the best and most acceptable” in the nation’s history, and said while delays in announcing results were inevitable due to voting complexity this year, including the referendum question as well as postal votes, there was “no scope for manipulation.”

But in a post-authoritarian Bangladesh, trustworthiness is not built on declarations; it will be built on remedies.

That is why various international observers and local actors contesting close races have already called for recounts where margins are too thin or rejected ballots appear unusually high. Local reporting from Dhaka constituencies described opposition parties raising objections to cancelled/rejected ballots and calling for recounts to be held under EC supervision.

Mirza Abbas became something of a poster story for this wider anxiety. Though unofficial vote counts showed BNP leader Mirza Abbas winning in Dhaka-8, his race was closely watched and remained heated. We saw international reporting about allegations of high ballot rejection rates and calls for a recount amid public rowdiness.

Separately, there was ample room for public comments about Abbas’s personal reputation as a politician. Claims about corruption, coercive muscle on the streets, or even “rowdiness” and “hooliganism” are all political allegations and public perception, not court rulings.

In a brittle democratic reset like Bangladesh is experiencing, the Election Commission does not have to referee politicians’ reputations. But it will need to ensure the counting process is beyond legitimate critique.

A reasonable baseline test would be simple: if parties can meet legal thresholds to challenge individual seat results, liberalize recounts where possible, publish polling station-level result forms where permissible by law, and adjudicate these complaints within a reasonable timeline. If done well, Bangladesh’s EC can turn a peaceful election result into a historically defensible one.

India, Hasina, and the Awami League question abroad: the diplomatic web

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wasted little time acknowledging the results. Indian media confirms that the Indian Prime Minister personally congratulated Tarique Rahman by phone after the results trended, sending a clear signal that New Delhi is coming to terms with the real result and BNP’s victory.

That welcome will set the tone for Dhaka’s relationship with Delhi moving forward, but arguably the stickiest diplomatic concern has less to do with celebrations, official statements, or even foreign minister-level diplomacy.

It concerns Sheikh Hasina personally and other Awami League leaders currently residing in cities such as Delhi and Kolkata.

Statements reported by Indian media and attributed to BNP suggest Dhaka will push New Delhi on this front, either through extradition requests or legal cooperation. It remains to be seen whether India will entertain such requests, much less act on them, but the stakes are high on both sides. Perceptions that New Delhi is shielding a “banned party” or providing political refuge to a deposed political network will only fuel nationalist anti-India sentiment in Bangladesh. Perceptions that Bangladesh seeks retribution or “witch hunts” against India-leaning political figures will chill New Delhi’s cooperation.

If there is one smart strategic takeaway for the incoming government and its supporters, it is to treat the Hasina question moving forward as a legal matter and a diplomatic conversation, not a political slogan or call to action. If Bangladesh seeks her return, it must build a credible extradition case grounded in documented legal complaints, basic due-process guarantees, and a process that looks more like justice than a victor’s triumph.

International response: alignment unusual, but skeptical optimism evident

What stood out to us about this election, from an international affairs perspective, was how warmly it has been welcomed by multiple governments with historically divergent views on Bangladesh.

Reuters, AP, and other outlets noted that the U.S., China, India, and even Pakistan issued statements signaling support for Bangladesh’s parliamentary election and Bangladesh’s return to civilian electoral politics. In today’s hyper-partisan international environment, that is an unexpectedly broad alignment.

But international goodwill is not guaranteed. If recent history is precedent, it is “acceptance with questions.”

International actors do not have high confidence in Bangladesh's politics, and making that confidence visible will require action and improvement in governance. Rapid recognition of a free and fair poll is easy; earning legitimate credibility for a new government takes years.

Reform or repentance? The “July charter” and pitfalls of winner’s comfort

The electoral math the BNP finds itself in now is the kind of majority that can make or break democratic reform in Bangladesh.

Reuters summarized BNP’s policy priorities in its victory statement as tied to its July Charter reform agenda and broader commitments to improving governance and rebooting the economy.

Public polling and sentiment we have seen indicates overwhelming support for constitutional reform through the referendum process alongside the election, which will place additional moral suasion on the winners to deliver.

The danger now is one that has afflicted Bangladesh’s major parties at different times: the presumption that, because you won big, you can also gobble up democracy.

In a post-2024 context, that path would be devastatingly short-sighted; it would mean betraying the very promise of last year’s uprising: that electoral cycles would not continue to be a “winner-takes-all” game of power.

Gender and minority rights: promises made, promises yet unfulfilled

It’s one thing to hold an election that qualifies as a democratic success. It’s another to ensure that the election authentically reflects the will of the people.

We’ve already seen reporters and analysts flag concerns that women’s candidacy rates and political representation in Parliament will not reflect the massive role women played at the street level of protest and civic engagement during the movement period.

Salil Tripathi highlighted this dynamic in particular, underscoring how few women ran for office in this election and what that means for rights and representation going forward.

Likewise, Jamaat’s resurgence, however, rebranded, keeps questions lingering over where social policies may shift under an Islamist opposition bloc that could seriously impact the rights of women and minorities.

International reporting even described the “balancing act” over women’s rights and minority protections as the “elephant in the room” for Bangladesh moving forward.

For BNP, the political calculus here should be obvious: if it does not want the opposition to monopolize moral capital on issues of clean politics and institutional reform, it will need to back its victories with clean governance and a citizenship that feels inclusive, not partisan.

What should we expect from Lutfuzzaman Babar’s return?

Lutfuzzaman Babar, who served as a minister for home affairs in the former caretaker government in 2007-2008, returned to Parliament on Saturday, having won Netrokona-4, according to BDNews24.com and other Bangladeshi media.

Mr. Babar’s return to politics is deeply controversial. To his supporters, he is a no-nonsense administrator. To his detractors, he is a hardened interior ministry apparatchik who has spent nearly two decades, not in jail, but awaiting trial on serious allegations.

Reporting by bdnews24 and others confirms Babar was imprisoned for nearly 17 years across several cases. Higher Courts would later acquit Babar in at least one major case related to illegal arms; other allegations we have seen repeatedly circulate about Mr. Babar over the years.

Questions immediately arise: will he take up the same portfolio as he held prior to imprisonment?

Our advice: Prepare for all of the above.

Three scenarios we anticipate seeing play out:

- BNP brings him back in as a regional strongman and powerful parliamentarian, but avoids placing him in critical ministries to avoid international scrutiny or alienating credibility.

- Betting on a cycle of law-and-order anxiety, BNP returns security-heavy tacticians from the previous era in hopes that public appetite for order will outweigh accusations of abandoning civil liberties.

- BNP allows him a seat at the table, proof that Bangladesh has turned a page on the Hasina-era’s imprisonment of politicians, but keeps him out of sensitive interior affairs and sticks to a new generation for day-to-day administration.

Options 1 or 3 would give Bangladesh the best chance of ensuring that Lutfuzzaman Babar’s return does not mean a return to the old ways. The new government will need all the credibility it can muster, both within Bangladesh and abroad, to kickstart reforms and incentivize investment. Allowing Mr. Babar a seat without putting him in a position to revert to old habits of politicized policing would send the strongest signal.

The “winner’s curse”: checklist of things that will define the decade to come

BNP should rejoice in its victory. But there are “day-one” challenges that will come with their newfound electoral mandate:

- Close or disputed seats: Address balloting complaints through recounts and investigations where votes were close; be transparent and quick about publishing results.

- Economy, jobs, inflation: Issues Reuters and others flagged will be a make-or-break test for the incoming government. Will it govern effectively or prove critics right?

- Justice, not vengeance: Holding accountable those who perpetrated atrocities and violence in 2024 will be necessary and popular. But it must be done lawfully and with some semblance of even-handedness, or it will backfire and invite international scrutiny.

- Islamists at opposition barricades: Jamaat won’t be part of the government, but its bloc is large enough to drive narratives on the street and in parliamentary debates. How BNP manages Jamaat-e-Islami will say much about this new government.

- Dhaka-New Delhi ties, and the Hasina question: How Bangladesh navigates the question of Hasina living in exile with India will affect this relationship for years to come. Court cases can take time, but equating grievances against India with Sheikh Hasina is a diplomatic loser.

- Deliver on reform: July Charter, referendum: this was the interim govt.’s platform initially. It’s BNP’s responsibility now. Don’t forget it.

- Rights, representation, and impartial administration: The levels of women’s participation, minority rights protections, and depoliticizing vital administration like police will be a true test of democratic restoration, vs. simple rotation of political elites.

How to really make this election “historical”

Five things Bangladesh can do more than any speeches or statements to ensure Bangladesh’s 12 February election is remembered for years and decades to come as a true democratic turning point:

- Establish transparent complaint/recount mechanisms for close seats.

- Announce a public, time-bound process for investigation of credible irregularity allegations;

- Publish a reform roadmap tied to mandates laid out in the referendum, complete with benchmarks;

- Commit to rebuilding non-partisan law-and-order (including professionalization of policing, de-politicization of administration); and

- Commit to national reconciliation. Justice for real abuse and excess. But not witch hunts.

This election was hard. Bangladesh just completed the most difficult part: holding a vote that the international community is prepared to accept as legitimate and peaceful.

Let’s see if it can do the hard work of proving that legitimacy is more than just an event. It’s a system.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published