Water as Power in the Asian Century

In Asia’s high mountains, rivers are no longer merely lifelines of civilization. They are instruments of power. India and China, two rising, resource-hungry giants, are racing to build colossal hydropower projects across the Himalayas, presenting them to the world as clean-energy solutions while quietly transforming water into a tool of geopolitical coercion. For lower-riparian states such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, this race is not about green transition or climate responsibility; it is about systematic denial of water, strategic punishment, and the erosion of sovereign rights.

The Brahmaputra, Teesta, Ganges, Indus, and Chenab are not abstract lines on a map. They are living arteries sustaining hundreds of millions of people downstream. Yet in the hands of upstream powers, these rivers are increasingly being dammed, diverted, digitized, and disciplined, often with deliberate political intent. What is unfolding is a new form of domination: hydro-digital hegemony, in which control over water converges with control over data, energy, and artificial intelligence.

The Himalayan Dam Race: Green Energy or Strategic Encirclement?

India’s grandiose US$77-billion announcement in June 2025 was not the first of its kind. The country’s northern neighbor, China, plans to build nearly 500 dams by 2030, including 63 over 100 meters in height. The Indian proposal envisions over 200 dams in the northeastern states, in the contested borderlands of Arunachal Pradesh and southern Tibet, which China still claims. Targeting a capacity of 75 gigawatts (GW), the plan aims not only to catch up with China but to outpace it by building an array of high-altitude water reservoirs. The Chinese Yarlung Tsangpo Lower Reaches Hydropower Project was also unveiled in 2025. Estimated at between 67–80 GW, the large-scale project alone would be twice the capacity of China’s Three Gorges Dam and could cost over US$160 billion.

Presented as climate change solutions, the projects involve secrecy and competition. While their potential to contribute to decarbonization is not in question, the scale of the build-out and deliberate disregard for international riparian norms bodes poorly for the climate-critical Hindu Kush Himalaya region.

Shared Rivers: A Chinese State of Exception

China is a hegemonic hydrological actor. It has refused to enter into water-sharing agreements for decades. It has the power and technology to exercise significant control over the six great rivers whose headwaters lie in its territory. Some analysts, like Brahma Chellaney, call it “hydrological hegemony” and argue that China is building “control and stranglehold over its downstream neighbors by retaining complete discretion upstream.” Blame for previous incidents has been put on the Chinese, most recently in 2000, when China released an outburst flood from the Yigong Zangbo that caused flooding in downstream Arunachal Pradesh. Because of the incident, Indian strategic analysts fear China could one day use water as a weapon by causing artificial floods or droughts.

India has responded with what amounts to hydrological tit-for-tat: militarization of the Brahmaputra by dams, rather than diplomatic engagement with China. The 280–300 meter Upper Siang Multipurpose Project is the centerpiece of this infrastructure build-out: an 11-GW behemoth that, if built, would be the largest dam ever built in India. The Indian government makes no secret of its intent: they call it a “national security necessity” and a contingency plan in the event of upstream Chinese misbehavior.

India, however, is also an upstream riparian and an aggressor toward its downstream neighbors, Bangladesh and Pakistan. India’s relationship with these two countries is a useful mirror of the hypocrisy in India’s stated objections to China’s dams and behavior.

Bangladesh: Where No Water Flows Freely

Bangladesh is one of the world’s most hydro-dependent countries and is already suffering under Indian upstream coercion. Chronic dry-season shortages have been engineered since 1975, with the commissioning of the Farakka Barrage. The crisis has led to multiple problems, including the intrusion of saline water from the Bay of Bengal up the Ganges basin, agricultural decline, fisheries collapse, and ecological degradation of the Sundarbans mangrove reserve.

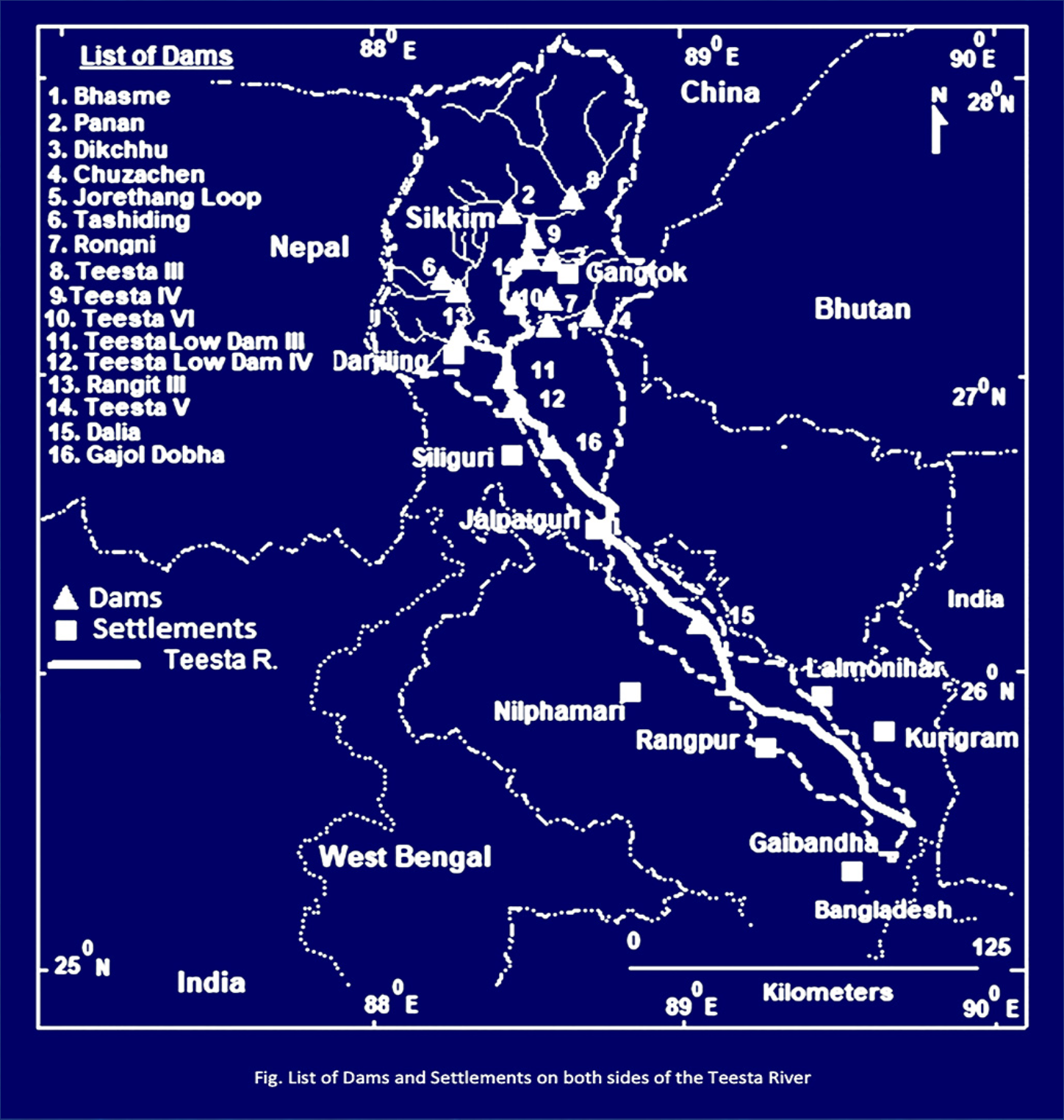

The Teesta River crisis is even more instructive. For years, India and Bangladesh have been negotiating over the Teesta. Still, India has balked at finalizing a fair deal, leaving Bangladesh at the mercy of India’s state politics in the power-sharing-sensitive state of West Bengal. During the dry season, when flows dwindle, the bulk of the river’s waters are reserved for upstream canals in West Bengal, while Bangladeshis have to get by on a trickle that is hardly adequate for irrigation in Rangpur and Nilphamari.

There is a clear pattern: water as political leverage, water rewarded to allies, withheld from adversaries, and punishment for assertiveness. Bangladesh’s lower-riparian status is of no consequence to India.

Pakistan and the Chenab: Hydraulic Retaliation

India’s rapid dam construction on the Chenab River is the more immediate concern. Claiming the dam structures are run-of-the-river projects compliant with the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), Indian dam construction on the Chenab and construction of canals for water diversion are now admitted by Indian leaders to be intended for the express purpose of having the “option” or “capability” to cause “disruption” to the flow of water to Pakistan.

The IWT is the last red line for the survival of South Asia. It has indeed outlasted three wars and several other crises since it was negotiated between India and Pakistan in 1960. India has explicitly threatened to “review” or “maximize” its rights under the treaty in response to political crises and military provocations. Language widely interpreted as signaling a change to the treaty terms, opening the floodgates to greater water withholding. For Pakistan, an agriculturally based economy whose food and livelihood security critically depend on Indus basin river flows, such an act would be a matter of existential national survival.

AI Dams: Artificial Intelligence Water Wars

What is different from previous eras of dam building, however, is the marriage of hydropower to AI and other digital technologies. China is closely integrating its Himalayan dam projects into the grid companies’ joint State Grid smart energy brain to manage data, electricity dispatch, and real-time water flow regulation. Artificial intelligence technologies are increasingly important to India’s parallel hydropower efforts.

As both states now race to build out data centers and AI compute facilities, hydropower capacity becomes a direct input into data capacity. Control over the flows of water increasingly means control over the flows of data via servers, satellites, and surveillance. Dams are now integral to digital infrastructure.

The Brahmaputra Basin as a Data–Energy Nexus Battlefield

The Brahmaputra–Yarlung Tsangpo basin has become a natural resource data-energy nexus battlefield in the high Himalayas where energy security, cyber issues, and geopolitics are converging. There are fears that either state’s dams and infrastructure could be dual-use bases for hydrological coercion or data espionage. For example, China’s PLA Strategic Support Force and India’s National Technical Research Organization have newly established cyber warfare units with a mandate to probe for vulnerabilities in smart grid and power infrastructure.

A targeted cyberattack on an upstream dam’s spillway automation controls or grid-balancing algorithms could produce the effects of a natural catastrophe, such as an induced flood or blackout. In a context of strategic mistrust and the lack of any institutional dispute-resolution mechanisms, the absence of a Brahmaputra commission or a binding treaty is a recipe for disaster.

Bangladesh and Pakistan are the Silent Victims

Caught between the upstream dams of China and India, the two other lower riparians, Bangladesh and Pakistan, have been mostly silent partners in decisions made by others about their own survival. There is no comparable multilateral structure to the Mekong River Commission or even the embattled Indus Water Treaty to ensure that the interests of these states are protected. International law, such as the principle of equitable and reasonable utilization, exists, but with little power to hold upstream powers accountable when they are the dominant regional hegemon.

The result is that Bangladesh has human-made water scarcity in addition to climate-induced risks. Pakistan faces political instability that intersects with food insecurity and water insecurity, squeezed in all directions between Himalayan megaprojects and geopolitical neglect.

A New Cold War over Water

The US has taken notice. During a visit to Delhi in 2025, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said he had raised the issue of China’s dam-building activities as a “coercive infrastructure strategy,” drawing on Southeast Asia's experience along the Mekong. The problem is that Washington’s identification of India as the solution and China as the problem is empowering India’s own downstream coercion.

The Himalayan water wars are not green infrastructure or climate change solutions. It is a new energy cold war where climate change is a convenient cover story for strategic competition. In which rivers become unwitting victims of the rivalry between upstream powers.

Conclusion

A Dam Is an Act of Sovereignty

Dams are not concrete. They are political statements, writ large in steel, sensors, software code, and server farms. They are acts of sovereignty that upstream powers use to write the geography of domination.

Asia’s future will be one of either water wars or water peace. Restoring the rights of lower riparian states must become the central diplomatic priority for regional order. Transparency, binding treaties, and genuine multilateral basin organizations are no longer an option. In the absence of these building blocks of shared sovereignty, the Himalayan water towers will remain a potential flashpoint where every cubic meter of water and every megawatt of power are coded as domination.

For Bangladesh and Pakistan, the message is clear: water denial is no longer an accident of geography. It is state policy. Collective and multilateral resistance is the only response.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published