by Helal Uddin Ahmed 22 August

The late British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli had claimed long time ago: “There are three kinds of lies: Lies, damned lies and statistics”. However, despite this well-known warning, opinion surveys based on statistical techniques have now become part and parcel of modern-day living, especially in Western societies. But people in the West usually take great care in ensuring accuracy of predictions and assessments by strictly adhering to sound, reliable and time-tested methodologies.

Developing countries like Bangladesh, on the other hand, still lag far behind in the wider applications of statistical techniques, and whatever little is done are often found to be methodologically flawed or inherently biased. Some examples of flawed opinion surveys can be cited from the past, including those conducted by The Daily Star (a leading national English daily of Bangladesh) during the early 2010s. The daily conducted and published these surveys regularly from 2009 to 2013 when such surveys had some relevance for national politics and electoral trends. But these were stopped since 2014 by the leading national dailies following the holding of a farcical parliamentary election in January 2014, when 154 out of 300 MPs were elected unopposed amid a boycott by opposition parties and arguably thinnest voter turn-out in the country’s history. The only exceptions have been the surveys by US-based IRI (International Republican Institute), but these have been viewed with suspicion by the general public and knowledgeable quarters because of some apparent absurdities in its findings after January 2014.

In order to make things clearer to the readership about the perils and pitfalls of biased sampling during surveys, let us first illustrate with an example how biased sampling can mislead people. Before the 1936 Presidential election in the USA, the American periodical The Literary Digest decided to conduct a survey on the likely outcome of the election. Around ten million telephone and Digest subscribers assured the editors of the magazine that it would be Landon 370, Roosevelt 161. The respondents were picked up from a list that had accurately predicted the 1932 presidential election. But this time, the whole survey exercise ended in a fiasco as the actual result was quite the opposite of what was predicted, with Roosevelt triumphing over Landon. So, how could there be a bias in a list that was already tested? It was then found that there was a definite bias, as people who could afford telephones and magazine subscriptions in 1936 were not a cross-section of voters. Economically, they were a special kind of people – a biased sample because a majority of them turned out to be Republican voters. The sample elected Landon, but the voters thought otherwise (Darrel Huff, ‘How to Lie with Statistics’, New York: W W Norton & Co., 1982: 11-26).

The sampling bias mentioned above can easily be compared with what was done with the opinion surveys conducted by The Daily Star of Bangladesh during the period 2009 to 2012, despite its claims of ‘adherence to internationally laid down methodology and ethical standards’. Let us prove our case by referring to the two opinion surveys published in 2011 and 2012. Up to 2011, the surveys were a joint collaboration of the daily and a marketing survey company of Bangladesh. Thereafter, it was conducted jointly by the daily and a little known research entity. There were reasons to believe that the same biased people were at the helm of the survey team during both these surveys, albeit under different umbrellas.

Let us first take up the case of 2011 survey. The last graph in the supplement of the concerned daily on Opinion Survey-2011 showed the composition of the sample population in terms of their political leanings (parties they voted for in the previous parliamentary election). The percentages were as follows: Awami League or AL (53%); Bangladesh Nationalist Party or BNP (20%); Jatiya Party or JP (3%); Jamaat-e-Islami or JI (1%); Others (2%); Cast No-vote (1%); Didn’t vote (10%); Wasn’t voter (1%); No response (10%). Interestingly, when added, the total percentage was 101% instead of 100%, which was a pointer to the callous manner with which the survey was conducted. Now, if only those who had voted in the election (79%) are considered, then the percentages turn out to be: AL (67%); BNP (25.2%); JP (3.8%); JI (1.25%); Others (2.5%); Cast No-vote (1.25%).

Let us now compare the actual percentages of votes won by the above-mentioned parties in 300 parliamentary seats across the country during 9th Jatiya Sangsad Election held in December 2008 (as obtained from the Election Commission and cited in the report ‘Election in Bangladesh: 2006-09’ (Dhaka: UNDP, 2010) with the ones obtained from the given sample-frame of Opinion Survey-2011. For ease of understanding, the figures have been shown in the following table.

| Parties | Voter Percentage

(Actual Election-2008) |

Voter Percentage

(Sample-frame of Survey-2011) |

| Awami League | 48.04% | 67% |

| BNP | 32.50% | 25.2% |

| JP | 7.04% | 3.8% |

| JI | 4.70% | 1.25% |

| Others | 7.16% | 2.50% |

| ‘No Vote’ | 0.55% | 1.25% |

The above table clearly shows that the sample used in the Opinion Survey-2011 was heavily biased in favour of the ruling party Awami League, which ultimately led to the unrealistic inferences made on various issues and subjects. As the sample population was heavily loaded with pro-ruling party voters, it was quite natural that they would tend to support the performance of their party’s government as well as the leaders.

A similar analysis of the Opinion-Survey-2012 conducted by the aforementioned daily by considering 92% respondents in the sample who actually voted in the December-2008 Jatiya Sangsad (JS) Election and by omitting those who ‘did not vote’ or ‘did not respond’ provides almost similar figures as in the previous case (Special Supplement of the daily on the Opinion Survey, January 6, 2012, page 11).

| Parties | Voter Percentage

(Actual Election-2008) |

Voter Percentage

(Sample-frame of Survey-2012) |

| Awami League | 48.04”% | 68.08% |

| BNP | 32.50% | 26.08% |

| JP | 7.04% | 3.26% |

| JI | 4.70% | 1.09% |

| Others | 7.16% | 2.09% |

| ‘No’ Vote | 0.55% | 0% |

The above table once again shows a heavy bias of the chosen sample-frame towards the ruling party Awami League that can be inferred from a comparison with the actual voting pattern in the 2008 JS election. The biased findings in the 2012 survey could once again be attributed to this overwhelmingly skewed attitude of the sample population in favour of the ruling party. This pattern of survey findings was once again observed in the Opinion Survey-2013 (published by the concerned daily on January 4, 2013); but interestingly, the survey bosses refrained from publishing the voting preferences of the sample population in 2008 election this time around.

Now, what could have been the cause of these hugely biased samplings in the surveys under review? Obviously, those who led the research effort as well as the team of survey investigators had a major role in it. In most likelihood, the top management had a strong political leaning towards the ruling party and was therefore desperate to depict the performance of the government in a positive light. If all these surveys are scrutinised together, then it becomes quite clear to an objective, neutral and impartial observer that a band of motivated and biased researchers had left no stone unturned to prove the supremacy of their preferred party in the eyes of the public. In the process, they had sacrificed the virtues of morality and professional ethics at the altar of blind party loyalty. But ethics and morality are supposed to be the cornerstone of any quest for truth, including those based on statistical exercises.

There is also another angle to the story. This may be labelled as professional dishonesty, which often leads to unintended consequences both in the short and long run. For example, the above-mentioned survey findings prior to the countrywide municipal elections might have misled the ruling party into believing that they had nothing to fear in the polls. This complacent and confident state of mind probably had a slackening effect in their municipal campaigns and prevented them from going all-out to win the elections. The result was there for all to see. Instead of doing the ruling party a favour, the survey leaders had probably done them a disservice.

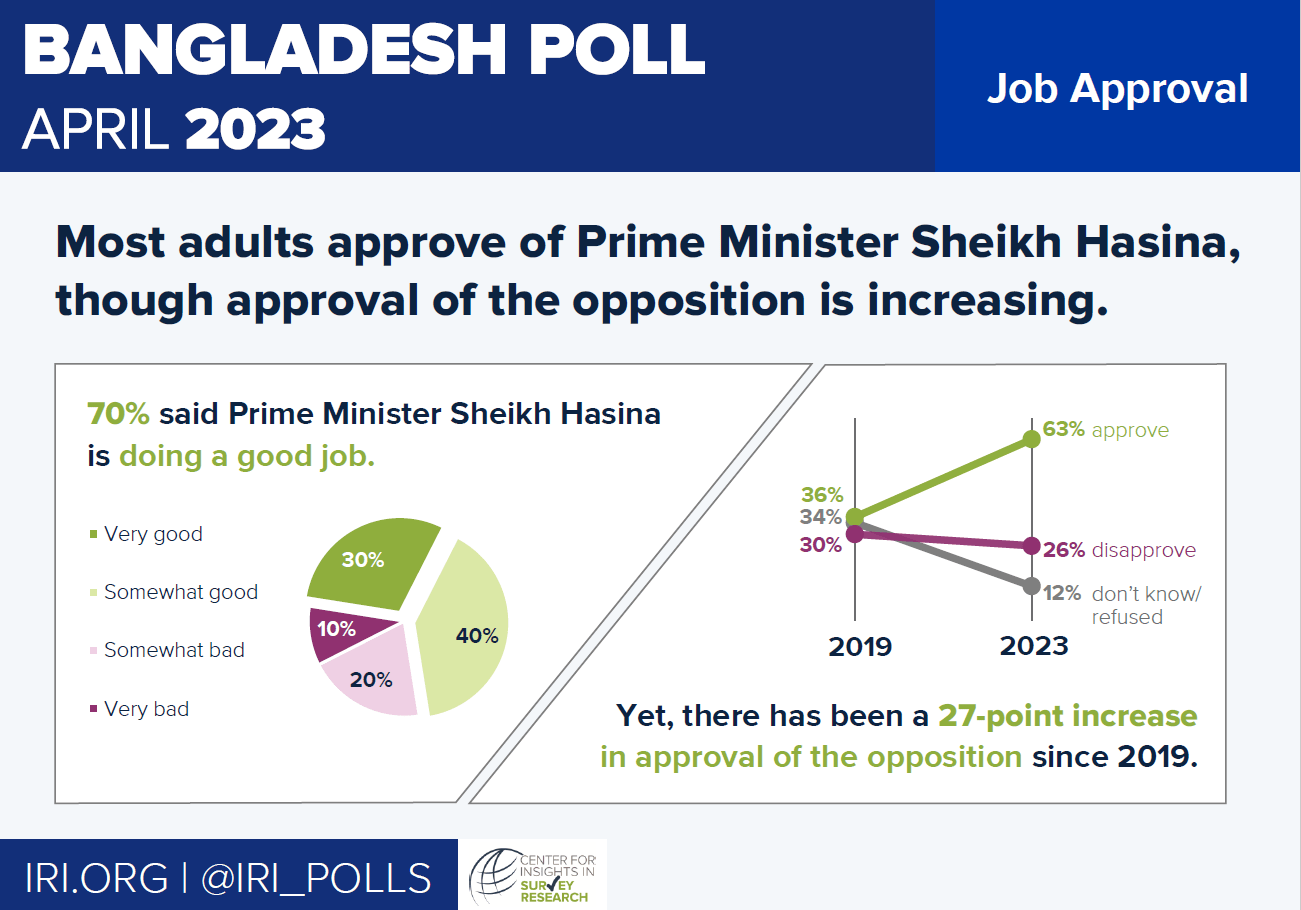

Coming back to the IRI surveys since 2013, the sample-frame appeared to have become irreconcilably biased after January 2014, which can easily be deduced from the given responses for the following questions: (1) whether Bangladesh is heading in the right or wrong direction; (2) approval rating of the prime minister. According to the data from IRI surveys, whereas 62% and 59% of the samples claimed that the country was headed in the wrong direction in November 2013 and January 2014 (62% said that the January 5 elections should not count as all parties did not participate), the disapproval rate dropped to an astonishing 39% in September 2014 even after a farcical election boycotted by the opposition was held in January. More amazingly, the disapproval rate continued its downward slide right up to September 2019 (recorded at only 15%) despite the heavily rigged election of December 2018 when the ballot-boxes were allegedly stuffed during the previous night. This could happen only if the sample was heavily biased in favour of the ruling Awami League. As for the second question, the approval rating of the prime minister had never gone down below 66% between 2017 and 2023 despite the worsening trends in the country’s politico-economic scenario. Again, this could not have happened unless the sample-frame was heavily biased in favour of the ruling party.

Consequently, the IRI authorities should thoroughly re-examine the credentials and track-records of their research teams both at the central and grassroots level, as well as the methodologies followed, in order to detect and rectify the loopholes if any. We also hope that all future opinion surveys in Bangladesh will strive to do a better job by strictly adhering to standard methodologies alongside keeping in mind the perils and pitfalls of biased sampling as elaborated above.

(Reference: “Surveys on Government Performance: Flawed due to Biased Sampling”. Published in The Financial Express on 10 January 2013 by the present writer under the pen-name Rubina Mahjabeen)

(Dr Helal Uddin Ahmed is a retired Additional Secretary of GoB and former Editor of Bangladesh Quarterly. Email: hahmed1960@gmail.com)