By James M. Dorsey

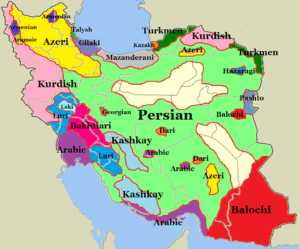

In the shadowy world of covert proxy wars, Iran is taking centre stage, both as a target and a player. A series of incidents involving Iranian ethnic and religious minorities raise the spectre of the United States and Saudi Arabia seeking to destabilize the Islamic republic. Not to sit back passively, indications are that Iran beyond its support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Lebanese Shiite militia Hezbollah, and Shiite militias in Iraq, may be strengthening its relations with the Taliban in Afghanistan.

In the latest signal of escalating proxy wars, Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guards Corp announced that it had “dismantled a terrorist team” that was “affiliated with global arrogance,” a reference to the United States and its allies, in the Islamic republic’s north-western province of East Azerbaijan. The announcement came weeks after Iran said that it had eliminated an armed group in a frontier area of the province of West Azerbaijan that borders on Iraq, Azerbaijan and Turkey. It also followed Iran’s assertion two months ago that it had disbanded some 100 “terrorist groups” in the south, southeast and west of the country.

To be sure, intermittent political violence in Iran cannot be reduced exclusively to potential foreign exploitation of minority ethnic and religious grievances in a bid to destabilize the Islamic republic. Nor can foreign exploitation be established beyond doubt despite multiple indications that it is a policy option under discussion in the United States and Saudi Arabia.

There is, moreover, little doubt that Iran’s detractors had no connection to a June 7 attack on the Iranian parliament and the grave of Iranian revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Tehran that killed 12 people and was claimed by the Islamic State, despite Iranian claims that Saudi Arabia was responsible.

Nor can revived agitation by Kurds, Baloch and Azeris be simply written off as foreign creations rather than expressions of long-standing and deep-seated grievances, even if the revival may in part have been inspired by secessionist trends among Iraqi and Syrian Kurds as well as developments in Catalonia.

There is however also no reason to exclude the possibility of the United States and its allies, including Saudi Arabia and Israel, seeking to exploit those grievances.

Iran is by no means a country wracked by political violence. Nonetheless, violence is gradually mounting. The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) announced in January that it was resuming its armed struggle not “just for the Kurds in Iran’s Kurdistan, but (as) a struggle against the Islamic Republic for all of Iran.” PDKI militants, operating from Iraqi Kurdistan, have since repeatedly clashed with Iranian forces.

Pakistani militants in the province of Balochistan reported a massive flow of Saudi funds in the least years to Sunni Muslim ultra-conservative groups while a Saudi thinktank believed to be supported by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman published a blueprint for support of the Baloch and called for “immediate counter measures” against Iran.

For sure, US and Saudi moves to counter Iran go beyond potential exploitation of ethnic and religious grievances. Supported by the Trump administration, Saudi Arabia has recently forged close ties to the predominantly Shiite Iraqi government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi despite Mr. Al-Abadi’s rejection of demands that he roll back the power of Iranian-backed Shiites who played a key role in the fight against the Islamic State.

Similarly, US President Donald J. Trump appears to be goading Iran to walk away from the 2015 nuclear agreement. Mr. Trump earlier this month refused to certify to Congress that Iran was in compliance with the accord. The United States has also sought to limit the benefits Iran should garner from the accord.

The Trump administration, in its latest move, blocked Iranian participation in ITER, a multibillion-dollar fusion experiment in France. Increased scientific cooperation was part of the agreement’s bid to dissuade Iran from pursuing nuclear weapons.

Included in this week’s release of 470,000 documents captured during the 2011 raid on Osama Bin Laden’s Pakistani hideout in which he was killed, was the Al Qaeda’s leader’s personal diary. The diary and other documents evidence Iran’s complex relationship with the jihadist group and serve to strengthen justification of the Trump administration’s tougher approach towards Iran.

Iran has not restricted its opportunistic, albeit calibrated support for militants, to Al Qaeda, but has played both sides of the divide in Afghanistan. In an indication that ties to the Taliban could strengthen because of US pressure on Pakistan to halt its support for militants, including the Taliban, Taliban fighters are looking to Iran as an alternative safe haven. “Many Taliban want to leave Pakistan for Iran. They don’t trust Pakistan anymore,” an Afghan fighter told The Guardian.

In a bid to counter Saudi influence in Afghanistan that dates back to the US-Saudi-backed jihad against the Soviets in the 1980s, Iran played in the wake of the US ousting of the Taliban a key role in the Bonn conference that united disparate Afghan factions behind the government of Hamid Karzai. Iran has since allowed the Taliban to open a regional office in the south-eastern Iranian city of Zahedan. Late last year, Iran hosted several senior Taliban figures at an Islamic Unity conference.

The record of past efforts to engineer regime change in Iran through covert wars is mixed at best and dismal on balance. There is little reason to assume that a potential new round will fare any better. If anything, the attempts persuaded Iran to keep its lines open to Sunni Muslim jihadists, who hardly are natural allies for a Shiite Muslim regime. At the same time, the two-year-old experience with implementation of the nuclear agreement as well as Iranian support for not only the Taliban but also the government in Kabul suggests grey areas in which reduction rather than escalation of conflict may be possible.