Introduction

Water is a critical resource without which the very existence of human being is unthinkable. Though 70 percent of the earth’s surface is water, access to water to man is uneven. The situation becomes critical as economies of nations continue to grow, new growth centers emerge, more and more industries come up fueling demand for more access to water resulting in growing imbalance in the demographic and many such related developments, and thereby throwing new challenges to water management. Also, as the population in the world continue to explode necessitating more agriculture production to meet the demand, access to water to enable this becomes more important. Historically it is proved that civilizations have bloomed around rivers. Principal rivers around the world have nurtured humankind. Since rivers pass through several countries, controlling the water by individual countries to meet their national interests have created problems and disputes. While there are some treaties signed by the affected countries for water management, there are cases where no such framework exists, creating a situation complicated in the period of crisis. Besides directly affecting with immediate consequences in a crisis, there are larger issues when water insecurity could fuel political instability and threaten the established social fabric. Climate change is yet another more significant issue that affects not just a nation or two but several regions, as well as the eco-system, could be adversely affected by bad water management. The existing social equilibrium would be a casualty as a result.

Water issue in South Asia involving four countries has been attracting world attention as some countries concerned tend to use ‘Water’ as a political and strategic weapon either to play a game of political up-man-ship or to dominate the smaller by throwing up their political and diplomatic weight and thus an unjust game of politics. More recently, the Brahmaputra River water issue between China on the one hand and India and Bangladesh on the other because of the former’s plan to block a tributary to complete a dam construction is a case in point that has fueled tensions. The other is Indian government’s intended plan to reconsider its commitments to the Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan, threatening to complicate regional politics further. Both the cases have political overtones as the countries involved are unable to resolve differences on other bilateral issues. The past experiences involving controlling stake on waters have not been pleasant, and the present simmering tensions do not throw up any rosy picture as well. The current analysis shall be confined to the controversy over the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) and how the possibility of revisiting the Treaty by India could reshape not only India-Pakistan relations but could have regional implications. While the IWT provides a framework to deal with water disputes when they occur, there are no bilateral or multilateral water management accords in the Brahmaputra River basin. Recent experiences demonstrate that even the existence of formal framework is inadequate to address the newly emerging issue. Why is that so?

Recent studies on water

There exist several serious studies on the IWT in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. There are also social activists who have raised the issue from the societal perspectives. Vandana Shiva’s celebrated works on potential ‘water war’ are well known. From the standpoint of a social activist, Shiva examined and made her case how public right was being misappropriated in an unjust manner. Brahma Chellaney’s pioneering works of several volumes examine the simmering disputes over water from the geopolitical perspective of the region. Chellaney reminds us how a common good could have not only regional but also global linkages between peace and war and how powerful nations and corporations have successfully manipulated to serve their vested interests, thereby creating a situation of unease peace. Uttam Sinha of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses has too done some outstanding work on the issue of water. Despite the existence of many volumes of literature throwing up some prescriptions for the policy makers to consider, the political leaders are still found wanting and unable to rise above the core national interests and accommodate perspectives of other stakeholders in the interests of regional peace and stability. As an ambassador of Singapore Tommy T.B. Koh observed recently in an event “water will likely emerge as one of Asia’s biggest security challenges in the 21st century”. He recommends that “equitable and sustainable management of Asia’s great river systems should be a priority on the global agenda.”

It is the time that policymakers take serious note of Chellaney’s warning that assuring adequate water supplies across the region is a serious challenge facing Asia. As the title of his book – Water: Asia’s New Battleground – suggests water has to be managed at multiple levels in Asia to secure peace. As water scarcity in the region threaten to intensify, national security and development issues of the countries affected become more intense, throwing up fresh challenges. Those need to be resolved. As some of the problems are also resource-linked territorial disputes, appropriate strategies need to be evolved to avoid conflict with a view to ensuring equitable distribution of water resources of Asia.

Water beyond Asia

Indeed, the water issue is not confined to South Asia alone; it also covers the larger Asia. The worry is Asia’s water woes are worsening. Besides disputes, flood and drought include a vast region extending from southern Vietnam to central India. China’s dam-building activities on Brahmaputra River have caused concern in countries located downstream because of impact on the ecology and environment. Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, known as the rice bowl of Asia, seems to be the hardest hit as are the 27 of Thailand’s 76 provinces, parts of Cambodia and Myanmar’s largest cities Yangon and Mandalay, besides of course many areas of India. These are disturbing developments pregnant with severe consequences and after-effects.

Water availability is prerequisite for farming as agriculture cannot always depend on rain. If farms growing agricultural produce are deprived of the required amount of water, it would result in inadequate supplies of food products and therefore adversely impact the global economy. If individual countries resort to control natural flow of water, the resultant water stress could result in water scarcity in the long term, and lead to tensions. In this respect, China’s recent actions on water issues raise concern. The issue becomes more problematic in the absence of adequate dispute-settlement mechanisms that might ensure rules-based cooperation.

Indus Water Treaty

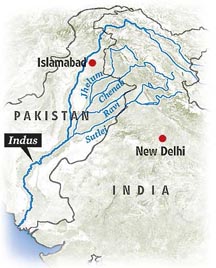

Unlike the Brahmaputra water issue, there exists a framework between India and Pakistan in the form of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT). The IWT is a water distribution treaty between India and Pakistan, brokered by the World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development). It was signed in Karachi on 19 September 1960 by Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru and President of Pakistan Ayub Khan. There is an increasing perception in India at present that the deal was disproportionately in favor of Pakistan and therefore interpreted as Nehru’s ‘Himalayan blunder’ that needs to be corrected.

Under the treaty, the water of six rivers – Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Indus, Chenab and Jhelum – was to be shared between India and Pakistan. The treaty is being seen now in India as one of the most liberal water-sharing pacts in the world. The treaty has survived wars of 1965, 1971 and 1999 between the two countries and much bad blood has flowed during and after the wars bedeviling bilateral ties, especially in cross-border terrorism issue. The IWT is considered one of the great success stories of water diplomacy. The terrorist attacks on an army base in Kashmir’s Uri on 18 September in which 18 Indian soldier were killed and Pakistan’s unwillingness to stop its territory being used by terrorists against India have led to the clamor in India that the existing water pact could be utilized as a political weapon to bring Pakistan to mend its ways. The question that begs an answer: Should that be the appropriate and desirable strategy to get Pakistan’s compliance with the demands to address the terrorism issue, the plethora of evidence to Pakistan sponsoring terrorism notwithstanding?

How does the IWT favor Pakistan as perceived in India? Dealing with six rivers and their tributaries, the waters of the eastern rivers have been allotted to India and oblige India to let the waters of the western rivers flow, except for certain consumptive use, with Pakistan getting 80 per cent of the water. Thus the treaty gives the lower riparian state of Pakistan more than four times of the water available to India. Pakistan has been not only less appreciative of India’s magnanimity but raised issues for apparently no justifiable reasons despite such favorable terms.

In 2010, Pakistan issued a non-paper raising concern over the issue of pollution, though the pact provides among other things that each party “agrees to take all reasonable measures before any sewage or industrial waste is allowed to flow into the rivers.” If the pact is hailed as a success model world over, where does it fault India then? When political issues come into the picture, things get messy, and therefore India-Pakistan relations over water become problematic. Does it mean then that IWT is a bad bargaining chip for India?

On the hindsight, it does not seem to be so as larger and more complex issues are so much enmeshed that it becomes difficult to isolate one from the other. Being a lower riparian state, India is already at a disadvantage on the Brahmaputra River issue vis-à-vis China, an upper riparian state. On the IWT, India is worried that in any conflict situation, China is likely to side with Pakistan, which could feel encouraged to violate the spirit of the IWT. Because of the history when water issue was at the center of the Kashmir issue until its settlement in the form of the pact of 1960, Pakistan might not hesitate to bring in Kashmir as another dimension to the water imbroglio. That would complicate the issue and thus needs careful reconsideration. If India decides to turn off the Indus tap or tamper with the pact as Prime Minister Narendra Modi has hinted by saying that “blood and water cannot flow together,” a new situation might arise that might be more complicated to be resolved. Revisiting the pact by India could be fodder for Pakistan to whip up anti-India feelings among Pakistan people.

Arriving at accords on water is too complicated and takes years and sometimes decades. There have been seven water-sharing pacts between countries in the region of which India is a part of three: Ganges Treaty with Bangladesh that took 20 years, the IWT with Pakistan, and the Gandak Treaty with Nepal. The Teesta water signing agreement is still pending. Therefore rocking the existing pact seems inappropriate.

However, the Modi government feels constrained with Pakistan’s growing involvement in fomenting and sponsoring terrorist activities in India. Therefore, amid growing strain in bilateral ties, the government has put in place four projects in Indus river basin to increase irrigation areas in the state of Jammu & Kashmir by nearly 2.05 lakh acres. Three of these four projects – Tral Irrigation Project in Pulwama, Prakachik Khows Canal in Kargil and restoration and modernization of primary Ravi Canal in Jammu’s Sambha and Kathua – are expected to be completed by the current fiscal. The fourth project of Rajpora Lift Irrigation is planned to be completed by December 2019. While the first three projects will help irrigate around 1.45 lakh acres of land, the Rajpora Lift Irrigation is expected to help irrigate 59,305 acres of land. All these works are supposed to cost Rs. 117 crore to be financed by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). India claims that it is within its rights to develop these projects without affecting the flow of water to Pakistan.

While India’s plans are firm, Pakistan too has its plan to build big dam projects on Indus River in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). It had approached the World Bank to fund in 2014 but was rejected because Pakistan was unwilling to seek an NOC from India. Then it approached the Asian Development Bank to commit funds of $14 billion. This too was refused. While acknowledging that the project on Indus River in Gilgit-Baltistan in PoK was important for Pakistan’s energy and irrigation requirements, Takehiko Nakao, President of the ADB, called for other partners who could join in funding the project. The planned capacity of the project is to generate a power output of 4500 MW.

Consequences if India abrogates the pact

What could be the consequences if India decides to abrogate the treaty? Pakistan had taken seriously when Modi said after the Uri attack that India would review the IWT by observing “blood and water cannot flow together.” As an immediate response, Pakistan took up the IWT issue to the International Court of Justice and World Bank since it had brokered the deal. Pakistan approached the World Bank to accelerate the process of appointing judges to a Court of Arbitration. The Treaty gives the World Bank an important role in establishing the Court of Arbitration by facilitating the appointment of three judges. The two signatory countries can appoint two arbitrators. Pakistan’s hawkish foreign policy advisor even warned that if India revokes the treaty, Pakistan will treat it as “an act of war or a hostile act against Pakistan.” At the moment it remains unclear if India would welcome to get entangled in legal issues.

The IWT is getting increasingly politicized. India intends to “maximize” the use of water from the rivers governed by Pakistan – Chenab, Jhelum and Indus – and India’s action will impact Pakistan as it depends on snow-fed Himalayan rivers for everything from drinking water to agriculture. For the record, the IWT gives India rights to use the eastern rivers – Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas – while Pakistan has control over the three western rivers. Because of Pakistan’s involvement in the infiltration of terrorists into India from its territory and its constant obduracy, India has toughened its position and launched a series of diplomatic offensives including pulling out of the SAARC summit in Islamabad and contemplating to downgrade Pakistan’s status as a trading partner.

In a lucid analysis, Joe Francombe writes for Global Risk Insights about the likely consequences if India abrogates the IWT. As a first retaliatory move to Pakistan sponsoring terrorist activities in India, India has put a stop to future meetings between the countries’ Indus Commissioners. When the World Bank brokered the pact through negotiations throughout in the 1950s before it was finally put in place, even the US and Britain extended active support as they perceived the agreement between the two South Asian countries as a means to address hostilities between the countries. That has obviously not happened during the past five decades or so. The treaty has survived for so long but now comes under strains.

As an upper riparian state of the Indus Basin, India is in a position of strength to issue the threat to prevent water flowing to Pakistan and therefore punish Pakistan. Such a move would have the inevitable political consequences as it would be potentially devastating for Pakistan. The economic implications on Pakistan would also be telling. But the question that arises: does India have the necessary infrastructure to store or make of the additional water it might accrue? As Francombe observes it “would require dams and diversion canal network on a scale that would take years to construct.” He further observes: “Preventing waters from flowing to Pakistan could even cause flooding in Indian-controlled parts of Kashmir.”

There could be other side effects as well. Projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) with significant Chinese investments will suddenly find short of water and therefore adversely affect the Chinese interests. Chinese retaliation in the form of denying Brahmaputra water further would be another troubling question for India. This is because just like India is the upper riparian state of the Indus Basin, China is the upper riparian state to India’s Brahmaputra River and therefore China would not hesitate to take revenge against India by siding with Pakistan. Chinese retaliation would be seen as a political consequence of India’s unilateral action and therefore undermine the spirit of cooperation that has helped the IWT survive for all these years. Seen as a model so far, the IWT would have lost much of its shine as a result. Can India afford to do that? Policy makers and the government in India need to answer this question while addressing the terrorist issue linked to Pakistan.

As India always upheld international rules seen in its support to the verdict by the international tribunal on 12 July on the South China Sea, it would be considered disrespect to such global norms if India implements its threat on the IWT. It is possible that India wants to get Pakistan’s compliance to address to the terrorist issue and thus issues threat to abrogate the IWT as a political weapon without really having the intent to do so. Though the Modi government started his tenure with the message of peace and good neighborhood policy by inviting all the heads of state of the South Asian states to his swearing-in ceremony and also made an unscheduled visit to Pakistan, if there is another terrorist attack on the Indian territory seen emanating from Pakistan, public clamor to strike hard would increase. In such a situation, the government in India might have a compelling reason to implement its threat to abrogate the Indus pact with unwelcome prospects for peace and stability in South Asia. The ball seems to be now on Pakistan’s court to resolve the cross-border terrorism issue first before other relevant matters could be addressed.

Use of water as a political weapon

The analysis above brings into the question if water can or should be utilized as a political weapon to settle the score on other contentious bilateral issues. Opinions differ. Viewed from a larger perspective, if India does turn the tap off, the result would be counterproductive. One cannot disagree with Uttam Sinha when he observes: “We have water-sharing arrangements with other neighbors as well. Not honoring the Indus Treaty would make them uneasy and distrustful. And we would lose our voice if China decides to do something similar.” Medha Bisht of South Asia University feels scrapping the pact is not an ideal diplomatic option.

There are hawks as well who hold a contrarian view. According to Brahma Chellaney, “India should give a credible threat of dissolving the Indus Water Treaty, drawing a clear linkage between Pakistan’s right to unlimited water inflows and its responsibility not to cause harm to its upper riparian.” He was obviously angry as most Indians were on Pakistan’s role in the Uri attack and recommends using water as a political weapon to punish Pakistan. Yashwant Sinha, who served both as foreign and finance ministers in the Vajpayee government and now a “brain-dead” politician when Modi government is in power, suggests that the treaty is abrogated. The official version, despite the threat, remains vague, except that the MEA spokesperson Vikas Swarup stressing the importance of “cooperation and trust between both the sides.” It transpires therefore that there is no substitute for dialogue and political engagement no matter how serious other issues may have strained relations.

The ball seems to be now on Pakistan’s court to resolve the cross-border terrorism issue first before other relevant matters could be addressed.