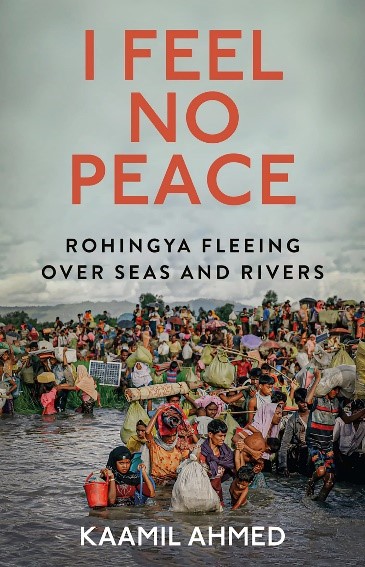

I Feel No Peace: Rohingya Fleeing Over Seas and Rivers, by Kaamil Ahmed, Hurst & Co., London, Hardcover, 248 pages, $29.95, ISBN: 978-1-78738-931-1.

266 pages, Kindle Edition

Published February 16, 2023

By Arnold Zeitlin 13 June 2023

Guardian newspaper reporter Kaamil Ahmed tells a brutal story in this book in a brutal manner, possibly the only way to relate the sad tale of the Rohingya, an oppressed people whose bitter fate the world seems inclined to overlook rather than resolve.

“Momtaz….sat there,” Ahmed writes, describing an attack by the dreaded Tatmadaw, the Myanmar army, on the Rohingya village of Tula Toli, “watching the bullets and the burning. She watched the soldiers slashing at Rohingya with such fury and frequency that their long knives became blunt. They wrestled her two youngest sons from her and threw them into the water….Her last son, her eldest, was bludgeoned around the head, then hacked and burned there on the river bank….the only survivor was Rozeya, who had tried frantically to pull her dead brother from the flames engulfing his body.”

The story never gets any better. The Rohingya tragedy festers today.

Momtaz Begum, whose husband also was killed, is one of several Rohingya whom Ahmed follows and interviews through his account of the violent Rohingya expulsion from Myanmar, the trek of survivors across the border to Bangladesh and the settlement of refugees in crowded border camps with minimal shelter, food and humane services, a humanitarian crisis made worse by murder, rape, a thriving drug trade, bribery, coercion, the trafficking of young women and governments unable to resolve the issue and anxious to rid themselves of these people.

Ahmed did not witness the Tula Toli killings but interviews in Bangladesh refugee camps and in Rohingya settlements in Malaysia helped him produce a story almost too damning to read.

Bangladesh, strapped to provide for its own, is the prime target of the flood of refugees. Initially it does its best to help these fellow Muslims. Then, when it appears Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina will not earn a Nobel prize for her country’s effort, the attitude shifts. When refugees resist attempts to return them to Myanmar, Ahmed quotes Bangladesh Foreign Minister A.K. Abdul Momen as saying, “if they are not willing, we will force them.”

Bangladesh js not alone in Ahmed’s narrative. Ahmed quotes an otherwise unidentified senior official of the UN High Commission for Refugees as saying, “The Rohingyas are a primitive people. At the end of the day, they will go where they are told to go.” ASEAN states, particularly Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, become targets for trafficking and resist refugees to the extent of pushing back boatloads of Rohingya trying to land on their shores back to the sea. “For a year,” Amed writes of the ASEAN states, “they continued wrangling for some common statement of intention, a way to escape scrutiny that could, at least, show that they had taken the issue of human trafficking seriously.”

Ahmed describes Myanmar’s Nobel Peace prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi at the International Court of Justice at The Hague in the Netherlands in December 2019 shredding her reputation for upholding human rights by defending the Tatmadaw and denying the accusations of genocide.

To counter the Myanmar contention that until the British colonizers of India brought Bengalis across the border to work the paddy fields in what then was Burma, there were no people such as the Rohingya, Ahmed goes back as far at 1404 to demonstrate that people had crisscrossed the border between what was Bengal and the Arakan kingdom. Buddhist Myanmar insists Muslim Rohingya are not citizens and belong elsewhere, Bangladesh, perhaps.

In the meantime, the Rohingya remain stuck. “This not a life,” a refugee named Imran tells Ahmed. “this is just survival.”

The Rohingya live in camps, otherwise unable to make a life in hostile Bangladesh, perhaps wanting to go home but fearing the Tatmadaw or scraping together a living in other Asian countries that do not allow them to become citizens.

Ahmed offers small hope. He ends his book with the glimpse of Begum Momtaz in her camp shelter in Bangladesh, cradling an infant son “born from her new marriage but her husband has not returned since she became pregnant.” She lives on donations “or selling off a part of her ration.” Rozeya attends a madrassa.

“Momtaz…would rather live out the rest of her life in Bangladesh than look again on the ground her husband and children bled into,” writes Ahmed. “”She has also heard that maybe Tula Toli refugees will be prioritized for resettlement in Australia. Though she has no clue about where in the world it is or anything about it, she thinks maybe it would be somewhere where her children could be educated….Rozeya now loves books and wants to learn.”