|

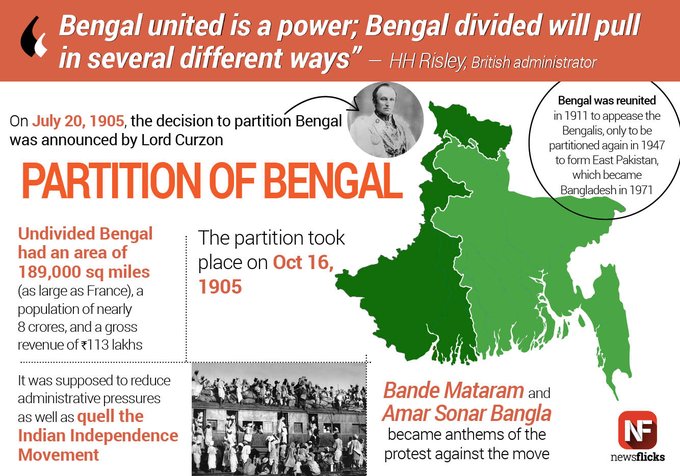

The Bengali bhadralok and their id?es fixe are not easily parted. The current year marks a full century since the Bengal Presidency was divided by the British rulers and a new province, Eastern Bengal and Assam, was carved out. To Bengal?s then influential Hindu gentry, it was an affront and an omen. That most important person, whose name was George Nathaniel Curzon, viceroy and governor-general, was vain to the core of his being. He detested the crowd of Bengali zamindars and lawyers hanging around in Calcutta. These species, he was convinced, were a thoroughly useless lot: the landowning community was a bunch of bloodsuckers lolling in the easy surplus.

The Permanent Settlement enabled them to extract from the hapless, mostly Bengali, peasantry in the outlying districts of North and East Bengal; the lawyers were even worse, constantly seeking to interfere, by their mindless nitpicking, with the process of administration. The viceroy was determined to stifle this whole lot. He thought up the idea of cutting Bengal up and thereby reducing the clout of the Hindu intelligentsia, since the Hindus would then find it less easy to get sustaining remittances from districts lying in another province. Curzon, however, pretended that his reason was most honourable: to improve the quality of administration in both the provinces, the new and the truncated old.

An uproar followed. Bengali politicians, led by Surendra Nath Bannerjea, pledged to ?unsettle? the settled fact of Bengal partition. They were joined en masse by the zamindars worried over the security of their land rights in the new province. What lent lustre to the protest movement was its emotive aspect; it was as if Bengalis were being invited to participate in matricide. The occasion led to a spate of major literary efforts, including dozens of patriotic poetry and hymns composed by Rabindranath Tagore. A more significant outcome of the turmoil was the irretrievable crossing over of the Bengali Hindu middle-class youth to political radicalism. The cult of violence emerged as the central datum. Over the next century, 1905 and patriotic fervour have been synonymous in the Hindu Bengali psyche. There was both a purity and a grandeur in the manner the Bengali youth thronged prisons, faced bullets and rushed to the gallows.

The bhadralok are a conservative tribe. They believe in adhering to rituals. The centenary of the Curzon decision is being observed with almost religious devotion in and around Calcutta. The daily schedule includes meetings, seminars, workshops, conferences. Learned papers are pouring forth, listing, and cursorily analyzing, particular facets of the anti-partition struggle. It is, indeed, a season of smugness for the bhadralok residue. After all, did they not succeed in their great movement? It was a famous victory, the British had to retract their decision. Curzon was humbled, the partition was annulled.

The myopic Hindu Bengali have consistently refused to take into account the impact of the anti-partition agitation on the mind of the Bengali Muslim community. The latter would have gained substantially were the partition not interfered with. Curzon?s original decision, whatever its motive, had offered hope of rapid economic and social progress to the Muslim masses in Bengal. They had been left way behind since the commencement of the raj. They bore the brunt of underdevelopment of agriculture ? and the economy in general ? under colonial rule, besides suffering the oppression and repression let loose by the Hindu zamindars.

Whatever job opportunities were available in the government sector was monopolized by the Hindus enjoying the advantage of earlier access to English education. The 1905 partition, the Muslims thought, would change all that; they would have a sanctuary of their own and need not suffer further from any inferiority complex; availing itself of the opportunities provided by the partition, perhaps a prosperous Muslim middle class would emerge within a couple of generations, and it would then be roses all the way.

The reversal of the decision to partition the province put paid to such dreams. The resentment of the Muslim intelligentsia against the Hindus naturally swelled. They were, they felt, cheated of something which was almost within their grasp, and it was not the British, but the Hindus who cheated them. That was the genesis of an increasingly unbridgeable Hindu-Muslim divide in Bengal. The so-called Bengal Pact, negotiated by C.R. Das in 1922, did not meet any success, largely because the higher echelons of the Congress leadership were not interested. A final attempt to restore a semblance of communal harmony was made, jointly and severally, by A.K. Fazlul Haq and the brothers, Sarat Chandra and Subhas Chandra Bose, in the Thirties and in the early Forties. The Congress was once more not interested. The inevitable happened; the Muslim League turned into an irresistible force.

It is, however, possible to think of an alternative landscape not allowed to take shape. Had the decision to partition Bengal been allowed to stand, the spread of education amongst the Muslims would have led to the quick emergence of a sensitive Muslim intelligentsia with a heightened social consciousness. Perhaps, from within this category, there would have sprung an exciting crop of thinkers and ideologues who would be inclined to re-define objective reality in terms of class analysis and not on the basis of the religious divide. Had events taken such a shape, individuals of the stature and bent of mind of a Fazlul Karim Sardar or a Munir Chowdhury would conceivably have captured the imagination of the young Bengali Muslim literati already by the Twenties, and not so late as they early Fifties.

The Bengal Moneylenders? Act and the Bengal Debt Settlement Act, put into statute by Fazlul Huq in the Thirties, might have been enacted in 1938 to save the immiserized Muslim peasantry in Bengal at least twenty years earlier. The Floud Commission would possibly have been ready with its recommendations on restructuring land relations a quarter of a century earlier than when it was actually drafted. Had all these things happened, the Muslim league would have come a cropper even as the bigoted Hindu oligarchies were stopped in their track. To sum up, if the partition of 1905 was allowed to stand, there would have been no partition of either Bengal or India in 1947.

The myopic Bengali Hindus deserve to be taught another home truth. It is because they made his life so miserable by their anti-partition hullabaloo that Curzon chose to deliver a final kick toward their direction: he recommended the transfer of India?s administrative capital from Calcutta to New Delhi. The recommendation was accepted. The ground proffered for the shift of the capital to New Delhi ? the practical difficulties of presiding over the administration of an empire stretching up to the Persia border from a remote corner ? was not altogether convincing. Washington D.C., London, Moscow, Canberra continue to be the capital cities of their respective countries despite their peripheral location. No, Bengal lost the nation?s capital simply on account of Curzon?s spite.

If only the partition was not made a non-fact at that juncture, Calcutta would have continued as the country?s capital on independence eve; it would have been awesomely difficult to shift the capital in the post-independence years. In other words, had the partition of Bengal decided upon in 1905 not been disturbed with, Calcutta, as the nation?s capital, would have been today as important, and as furiously growing, as New Delhi is, and no prime minister would have ever dared to describe it as a dying city. Such thoughts are anathema to the proud Bengali bhadralok. They always know the best, they prefer to be marooned in their mythology.