by Venkkat G 21 October 2022

Violence is a term that is often attributed with a negative connotation conventionally. Most of the religious teachings and almost all of the moral values condemn violence to varying degrees, at least in theory. It is so much considered an antithesis of anything remotely positive that peace is at times defined in terms of “absence of violence”. It is no wonder that violence as an act has more or less attracted universal condemnation across time and space, and across societies and civilisations. However in reality, it is not always so simple and straightforward, and the intricate nuances come to light when we dig deeper into it.

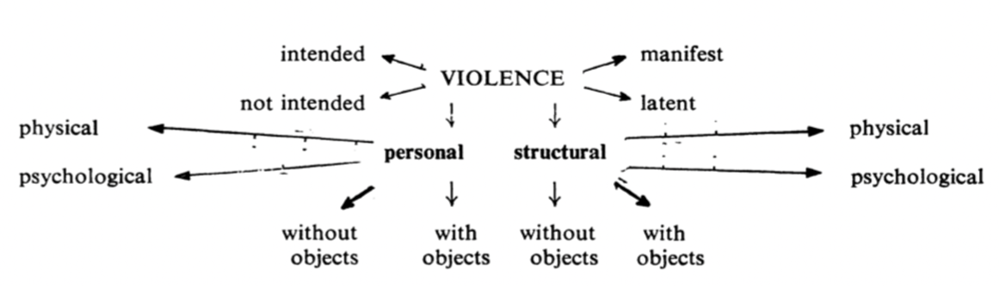

The famous political scientist Johan Galtung talks about the various types of violence that are being perpetuated on a day-to-day basis in the world around us (Fig 1). Talking generally, this violence can be perpetuated between individuals at the family level, between groups at the societal level, between communities at the national level and between countries at the global level. This violence can even be perpetuated in a manner that neither the offender nor the victim is even aware of the violence being committed.

Figure 1: A Typology of Violence (Galtung, 1969:173)

Violence in most of these cases is considered unjustified as it serves to further the cause of injustice over that of justice. Very often, it is unleashed by the dominant sections against the subordinate ones. Violence by men over women, upper castes over lower castes, majority community over the minorities, capitalists over the workers, and imperial nations over the colonies etc. falls within this category.

Nevertheless, under certain special circumstances violence is considered justified by some, if it serves to further the cause of justice over that of injustice. This usually involves the violence unleashed by the subaltern sections to structurally alter the hegemonic unjust status-quo existing in the society. Examples of this include violent decolonization as advocated by Frantz Fanon, class struggle as advocated by Karl Marx, anti-racial struggle as advocated by Malcom X, armed Tribal movements advocated by Naxalite groups etc.

However, this proposition is neither unambiguous nor uncontested. This is because of several reasons. First of all, it concerns the principle of using violence as a means of attaining justice. Political thinkers like Mahatma Gandhi had advocated for the continuity between means and ends, arguing that an unjust means cannot be pursued to attain a just end. Next concerns the effectiveness of use of violence as a strategy in practice. In almost all cases, any attempt in using violence to challenge the status quo is met with an even greater violence to maintain the same, starting off a rapidly deteriorating downward spiral of violence.

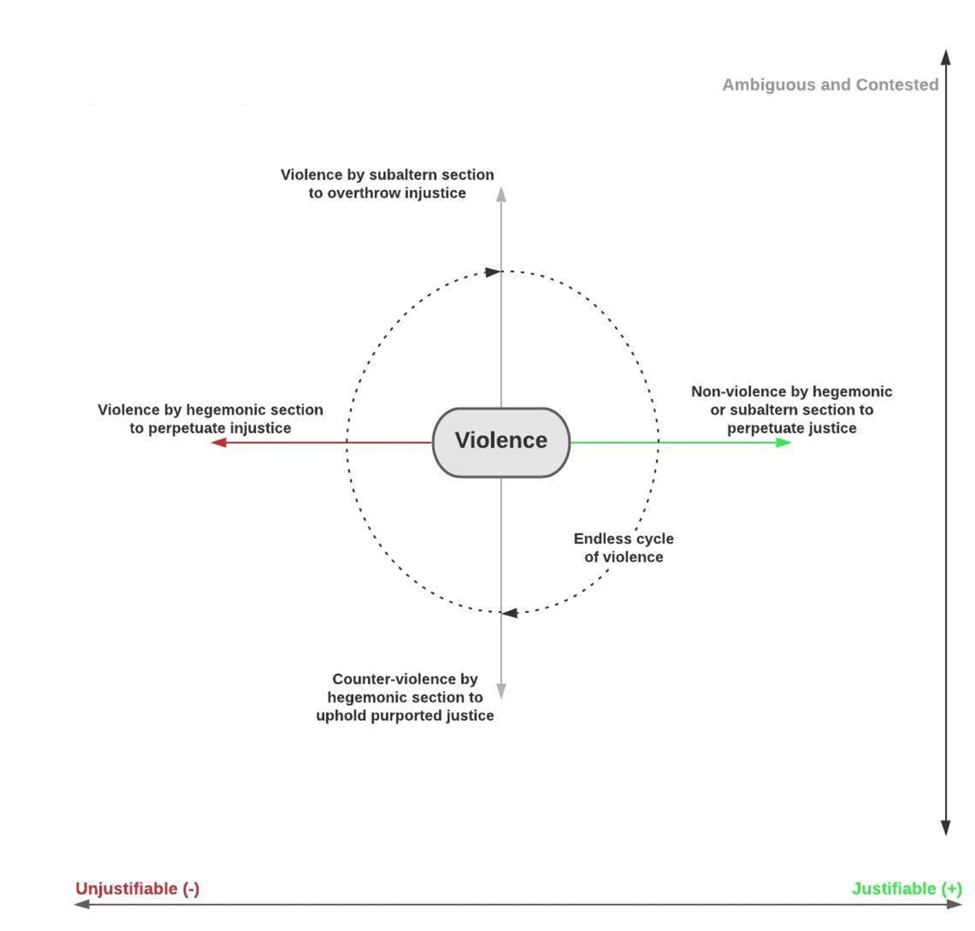

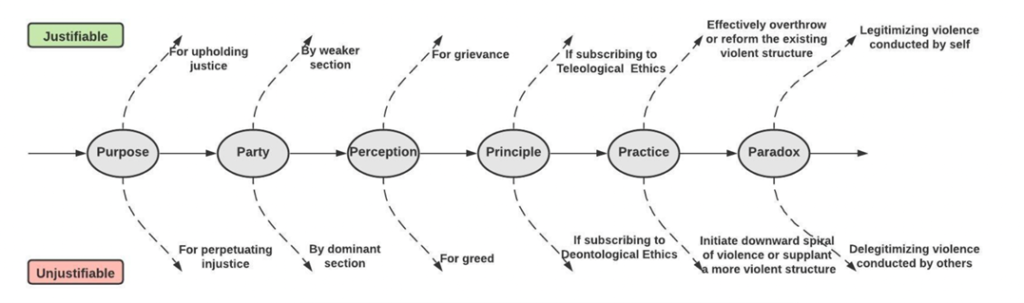

Third relates to the perception of structural injustices in the first place. Many a times, the greed of certain vested interests in the society is rebranded as the grievance of the entire populace, turning them into mere pawns in the political chessboard played between the elites. This results in the larger mass to be at the receiving end of much of the violence that it entails, with them not gaining anything substantial out of it. Finally, is the very paradox associated with justice itself, where what is perceived as just by one party is perceived as unjust by another and vice-versa. This prompts both the parties to justify their actions for upholding their purported sense of justice. All of this makes violence a seemingly straight forward, but contrastingly complex topic to deal with (Fig 2). Its justifiability and unjustifiability can be better illustrated with the help of an example of the Kashmir conflict.

Figure 2: Shades of Justifiability and Unjustifiability of Violence

Kashmir Conflict and the Shades of Violence

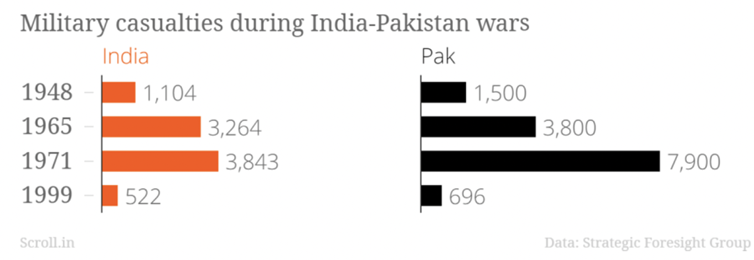

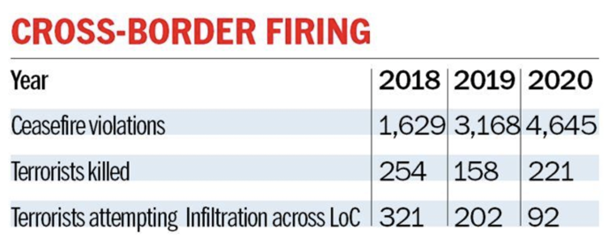

The Kashmir conflict has been inextricably linked with violence from the very day one of its genesis. It began with large-scale violence in the form of First Kashmir War in 1947 between India and Pakistan, which claimed the lives of over 7,000 combatants together on both sides and wounded another 17,000[1]. This formal violence taking place between states was overshadowed by an even more gruesome informal violence taking place between the communities. Cold blooded genocide was unleashed by both Hindus and Muslims against each other under the shadow of partition and war. Approximately 20,000 to 237,000 Muslims were massacred in the Jammu region[2] and several thousand Hindus were likewise killed in Kashmir. The violence has continued unabated ever since. The two neighboring countries have already gone for war three times in the past, and the prospects of a peaceful resolution of disputes is nowhere in sight (Fig 3). Cross- border violence continues unabated and ceasefire violations appear to have become the norm (Fig 4).

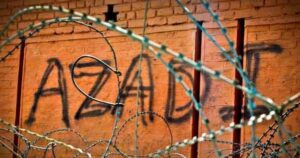

Ever since the 1990s, violence has taken a turn for the worse with the revival of Kashmiri insurgency and the azadi movement. The conflict has claimed the lives of 41,000 individuals ever since, with 14,000 civilian deaths, 5,000 security personnel and remaining 22,000 militant casualties[3] (Fig 5). All sides have their fair share of blame for the situation unfolding in Kashmir. India for its part is accused of grave human rights violations in valley in the form of fake encounters, pellet gun injuries [“killed 18, blinded 139, injured 2,942” between 2016 and 2019][4], civilian killings, enforced disappearances [around 8,000-10,000 since the 1990s][5] and sexual assaults. It has initiated ‘Operation All-Out’ to step up its anti-militancy operations, leading to a recent spurt in violence in the region (Fig 6). The militants on their part have unleashed untoward violence against the Kashmiri Pandits, killing about 400 individuals and displacing around 70,000 families[6]. It has also conducted numerous kidnapping of high profile victims, assassination of pro-India factions, targeted killing of politicians and state police personnel, attack against security forces, organized crime and terrorist activities. Similarly, Pakistan is accused of cross-border infiltration [around 300 terrorists each year (Fig 7)], unleashing terror attacks, supplying weapons, and supporting insurgencies against India.

Figure 3: Military casualties during the three Indo-Pak Kashmir Wars of 1948, 1965 and 1999 (Source: Scroll)

Figure 4: Scale of Ceasefire Agreement Violations across the Indo-Pak border (Source: Scroll)

Figure 5: Human cost of Kashmir Conflict since 1990s (Source: South Asia Terrorism Portal)

Figure 6: Increased violence in Kashmir since 2014 (Source: The New Humanitarian)

Figure 7: Cross border infiltration from Pakistan (Source: The Tribune)

However, going by Johan Galtung’s classification, direct and physical violence is only one of the several forms of violence which is being perpetuated in the Kashmir Conflict. The existence of structural violence can be said to be at the root of conflict, in the form of so-called ‘occupation’ or ‘colonization’ of the valley and the denial of ‘independence’ and ‘statehood’ to its people. This form of indirect violence imprisons its victims within the structures of injustice which is omnipresent and omnipotent, but where fingers cannot be pointed out against anyone in particular. The conflict was brought about by the structural constraints imposed by the circumstances prevailing at time of partition and the imperatives of statecraft. Equally significant is the psychological violence unleashed by the parties to the conflict on the general populace. Activities of the Indian state like overt militarization of the valley, cordon and search operations, preventive detention and enforced disappearances cause untold mental pain and suffering to the common people.

Another important aspect is that of the unintended violence which may be accidentally carried out by security forces, like in the case of pellet gun injuries, civilian casualties, crossfire mishaps, and accidental encounters. A not-so-talked-about facet of violence is the one committed against non-objects, like, in this case, the Kashmiri culture and identity. India’s policy of revocation of Article 370 might bring about irreversible demographic changes that threaten the Kashmiri society. Last but not least, Galtung broadly defined violence as the set of circumstances “when human beings are being influenced so that their actual somatic and mental realizations are below their potential realizations.” On this note, the never-ending saga of lockdowns, blockades, boycotts, internet blackouts, censorships, seditions, and strikes unleash unaccounted violence against the Kashmiri populace, by denying them the opportunity to attain their true potential.

Violence as a Means for Justice: Interviews and Inference

The scope of this article is confined to the interrogation of the question whether violence is a justifiable means for attaining the end of justice or not. In pursuit of this, individuals from in and around the conflict zone in Kashmir have been interviewed to capture their perspectives and views on the topic. A total of three interviews have been taken from interviewees belonging to three different positionalities and stand points in the conflict in order to capture the comprehensive picture of the same. The first interviewee is an ardent human rights activist from mainland India sensitive to the Kashmiri cause. The second is a resident of Jammu district in the state of Jammu and Kashmir who primarily subscribes to the Indian security narrative. The third belongs to a Kashmiri ethnicity and is a resident of the valley who throws a light on how the conflict is being perceived from the actual ground. The interviews are duly attached below.

One thing which readily strikes anyone who goes through the interviews is the fact that all three of them unambiguously acknowledge the fact that violence in any case is not the ideal solution to the question of fighting injustice. Similarly, although quite surprisingly, all of them subscribe to the view that under certain circumstances the use of violence is justified and we cannot put a blanket label of unjustifiability to violence. Even though non-violence is the preferred path by a huge margin, in many cases it remains ineffective, meriting the use of violence to challenge the structural injustices present in the world. However, the distinction lies in who’s violence is to be considered as justifiable in the face of mutually contradictory claims of purported sense of justice by both the sides.

While the interviewees 1 and 3 talk about granting partial legitimacy to the violent struggle carried out by the Kashmiri side, interviewee 2 talks about the use of violence from the perspective of Indian security forces. What is also interesting is that the interviewees, irrespective of whichever side they believe in, do not outrightly reject the claims and counter claims of the other party concerned. Rather they end up choosing sides based on their own self-conception of the purported sense of justice that they subscribe to. This in turn might be influenced by their own socio-religious-political identity, moral values and personal experiences. Finally, all of them are skeptical of the practical effectiveness and long term sustainability of violence as a strategy, being fully aware of the unintended consequences it brings for all.

Conclusion

If we can make anything out of all of our above discussions, it is only the reality that violence does not come out as clear black and white, but rather in all possible shades of grey. The justifiability and unjustifiability of violence is non-decipherable, just as the very concept of justice and injustice is itself non-definable. This brings us down to the need for conceptualization of a theoretical framework centered around the question of 6P’s, viz. purpose, party, perception, principle, practice and paradox of violence to determine its justifiability and unjustifiability. This approach, with all its due limitations and constraints, can help us to deal with the issue in a more systematic and structured manner (Fig 8).

First, coming to the question of purpose, it has to be determined whether the execution of violence serves to further the cause of principles of justice, or whether it exacerbates the status-quo structures of injustice. Similarly, the party which unleashes violence has to be identified whether it belongs to the dominant hegemonic section of the society or the subordinate subaltern one. An equally important aspect, if not more, is the question of perception about the given struggle. It has to be established whether the struggle is carried forward to address the genuine grievance of the masses, or it is done just to benefit the greed of certain elite sections of the populace. Many times, a sense of injustice is wrongly established, and a feeling of victimhood is falsely claimed to legitimize the use of violence in order to gain a definite political edge.

This brings us to the question of which principles of justice one chooses to believe in. If one subscribes to the Deontological or Kantian Ethics, then non-violence has to be strictly adhered to as a matter of principle irrespective of its effectiveness. However, on the other hand, if one chooses to adhere to Teleological or Utilitarian Ethics, violent means may be pursued if they can bring about favorable ends. Similarly, the practice of violence has to be continuously monitored and objectively evaluated for the kind of trajectory it is taking. It could produce an overall positive impact by making the hegemonic forces of violence retreat in the face of just attacks. Or it could take a negative turn by inviting retaliatory violence, setting off a downward spiral, and replacement of the existing structure with an even greater unjust and violent one.

Finally, it all comes down to the very paradoxical nature of justice itself. What is perceived as justice by one side is considered injustice by the other? The saying goes, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”. Both sides attempt to justify their acts of violence in the name of their self-conceived notions of justice while unjustifying similar actions by the other side. It is rather disappointing to know that there are no definite answers to the questions we set off to explore at the beginning of this paper. However, an insightful understanding of the subjective nature of justice, and its ambiguous relationship with violence will enable the reader to appreciate the complexities associated with the subject. This can prompt an individual to be sensitive to the perspective of the other side, which can lay the foundations for an amicable resolution of disputes and a more peaceful future hopefully.

Figure 8: 6 P’s Conceptual Framework for Delineating Justifiability and Unjustifiability of Violence for Attaining Justice

Interviews Conducted

(Note: The interview transcript may or may not be included in the article, as the editorial team best deems appropriate.)

The interviews were taken with the due prior informed consent of the parties concerned. Non-disclosure of identity and protection of privacy was committed at the onset and have been maintained accordingly. The interviewees were selected keeping in mind the imperative of identifying individuals with varying and preferably contrasting positioning in the dispute, so as to provide a comprehensive perspective. Diversity is ensured in terms of ethnicity, language, region, religion, political inclination and philosophical orientation. The first interview is conducted through text messages over a social media platform. The second interview is conducted through voice messages over a social media platform. And the third interview is conducted vocally over the telephone medium. The interview proceeded informally to capture the true views and opinions of the interviewee, unhindered by formal procedures. Because of the same, the original interview transcript had to be edited to make it in a presentable format. However, due care has been taken to ensure that the real essence of the responses was not lost, damaged, or manipulated. Most of the grammatical, typographical, and linguistic errors have been left untouched, which is to be kindly ignored.

Interview 1: Human rights advocate

Q: Can we get started?

A: Okay

Q: So.. first of all, how would you describe Kashmir conflict in one sentence..

A: Travesty of justice. Innocent victims of vested geopolitical interests

Q: And how do you view the movement by Kashmiris..

A: Present movement or past?

Q: Let’s talk about the present, maybe..

A: I feel the response by the people has been extremely mature, despite the brutalities of the Modi regime. Perhaps it’s got more to do with the total oppression of the government (violating all human rights laws in the process) than with any inherent maturity of the Kashmiris.

Nevertheless, considering the scale of injustice, it is still surprising that there was a strategic restrain from the extremist elements within the Kashmiris. A reckless, violent action at this point could have completely discredited the movement, and legitimised the Indian government’s actions, in the global community.

Q: Even though a majority of the populace is against the adoption of violence per se, there is a minority but significant section which believes in the adoption of violence mean to counter the inherent injustices brought about by the status quo. How do you perceive this section?

A: I’m very ambivalent on the topic. I strongly believed peaceful dialogues were the way forward. But after putting myself in Kashmiri’s shoes, I can’t blame him for getting his blood boiled due to the injustice as well as the daily humiliation by the Indian state.

Now, even with the sake of objectives, you can’t blame one for thinking that you need to talk in the language that this government understands. Let us not be mistaken that the current actions of the government in Kashmir is nothing short of outright VIOLENCE!

Violence doesn’t always have to be bodily harm. Imagine putting a person inside a cage for years altogether- denying him rights, mobility, communication, etc. That’s worse than torturing, actually. The government is doing the same for an entire state.

Q: I completely understand your perspective that non-violence might not always be a very effective strategy in countering the inherent injustices inbuilt into the existing structures. But isn’t the adoption of a strategy of violence self-defeating? Won’t it set off a downward spiral of violence after violence? Isn’t that ultimately antithetical to the interests of the very people whom they seek to serve?

A: What has been happening in Kashmir has always been a downward spiral.

Also, suffering (temporary, hopefully) yet dignified existence is preferable to ‘peaceful’ humiliation

Moreover, we have many historic examples where temporary violence has achieved lasting peace. Including almost all the independence movements across the globe.

*not almost all, but many

Q: There is also a counter perspective that while non-violent struggle brings about long-lasting peace in the form of democracy (as seen from the example of India and South Africa), non-violent struggles lead to the establishment of dictatorial and totalitarian regimes (as seen in the case of China and most other African nations). How would you react to that?

Also, don’t you think the violent struggle in Kashmir, if they attain the so-called ‘Azadi’ hypothetically speaking, would result in an outcome that none of its people would have hoped for.. Like another Pakistan or Afghanistan in the region where people do not exercise any real rights?

A: Response to First para.

I think it is cherrypicking examples to suit one’s cause. The establishment of the USA, the birthplace of modern democracy, was a result of a violent struggle. Also, whether people are happier (or let’s even say human rights of the majority population) in a post-revolutionary China or a post-peaceful freedom movement, India is very debatable

Second part

Yes, sadly, that is a real and dangerous possibility. But that’s somewhat like denying a motorcycle to a kid, saying what if you meet with an accident. Not the perfect analogy, but still.

Q: So you believe that violence, even though not the ideal approach, is still nevertheless a partially justifiable one for the purpose of attaining one’s purported sense of justice.. To be the devil’s advocate here, what if I apply a similar logic from the perspective of the state? That it can unleash violence as it deems necessary for attaining the sense of justice it sincerely believes in. That of countering insurgency, battling terrorism, upholding territorial integrity, and upholding its national interest.

How would you react to that?

A: It is obvious that the present government’s actions on Kashmir are based on domestic political calculations rather than any larger interest. For all the terrorism, national interest, etc., the most important thing is to win the hearts and minds of people. Completely alienating them with such does not help in achieving any larger interests either.

Interview 2: Resident from Jammu

Q: So let’s start it.

A: Ok

Q: How would you describe the Kashmir conflict in a sentence?

A: Religious, and cultural conflict

Q: And how would you identify the Kashmiri movement? Would you call it insurgency, secessionism, terrorism, etc., or would you rather call it a legitimate freedoms struggle or independence movement? Or something in between the two

A: Not every Kashmiri is a separatist. The conflict is the use of arms for the demands. It was KKLF who started it. It could’ve been a democratic process. There is external power that plays a major role in the conflict

Q: How effective do you think the strategy of non-violence would be in the face of structural contradictions and injustices which face the general public? And do you subscribe to the view that sometimes violence is justified in order to attain the larger goals of justice?

A: Use of non-violent methods is very important because, over time, there have been lots of faceoffs between the local public and the armed forces. So there is a great trust deficit between the people and the security forces. So the use of non-violent methods would encourage dialogue, and dialogue is essential in this conflict.

For the second part of the question regarding whether violence is justified. In the first place, we cannot justify violence. But if the rebellious groups are using violence, what other options do the state have left? They have no other option, but the neutralize them. Otherwise, they will create more fear among the masses. So violence, in defence can be justified to some extent.

Q: Okay.. So you have just mentioned that violence is sometimes justifiable when it is used by the armed forces to neutralize the rouge elements within the Kashmiri society.

I was talking to another friend of mine, who said entire the opposite thing. He said that in the face of all the injustices and violence that Kashmiris are facing, their use of violence to uphold their purported sense of justice, which they believe in, is justifiable. How would you react to that.. gain.. he said that it is not ideal.. but it is sometimes justifiable..

A: As far as that case is concerned that violence is justified, it’s very simple to analyze that position like “someone’s terrorist is another’s a freedom fighter.” So it’s all about perspectives and how they think the people are fighting for their cause. But for the rest of India, their use of violent methods is not justified. It’s very simple.

Q: Okay, so.. the point which you made that ‘someone’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter’ is a really good one.. I would like to further build upon that perspective and take the discussion a notch higher..

Earlier, you mentioned that you somewhat agree to the perspective that violence by security forces is somewhat justified to neutralize the violent elements within the Kashmiri society.. But you are fully aware there will be a lot of other people who feel the same from the other side..

Knowing this well, are you willing to change your perception of violence by the security forces, or do you still firmly stand by your earlier statement..

If so, why, if not, why?

A: I would like to stand by my earlier statement because what other options do they have? Its simple, someone else is killing you. What else can you do at that point in time?

Interview 3: Kashmiri Youth

Q: Can you elaborate on the use of violence as a strategy to attain justice with the example of the Kashmir Conflict?

A: As far as I can see, my experiences would be that when the avenues for any peaceful resistance are blocked, there are people who would see violence as the only way. See, for example, when we talk about Kashmir, since 1947, it has been an issue, right? Obviously, like when India and Pakistan got divided, it was primarily based on religious lines right. So naturally the people belonging from the valley had the tendencies to side with Pakistan. And those tendencies were since 1947 again and again violently cracked down. Those voices weren’t heard, they weren’t given avenues, and whatever promises which were made it didn’t happen that way right.

So the first major violence broke out in 1990 militancy right. The mainstream narrative in the valley was pro-Pakistan or pro-Independence, and it was the voice of the people. They chose contest the elections, enter politics, and raise their voice through democratic ways right. But what happened in 1987 was that majority of people voted for them, but the Indian state completely rigged the elections. And everyone knew that it was a rigged the election and the results were not like what the people voted for, the people naturally resorted to violence. They thought that we had done our part, we chose peaceful means, we chose to stand in the elections and fight the elections, and raise our voice through democratic means. But when that too was blocked, then the majority of the people resorted to violence because they thought it was the only way. That thing got crushed around 1995 by the heavy hand of the government, but the sentiment doesn’t die that easily right? That sentiment is always there, and if there is some ignition at some point, it ignites the sentiments again.. We saw that sentiments and protests coming up over and over again in 2008, 2010, 2016 etc etc.

My point is that when peaceful means are not available, when peaceful means are crushed, or when people feel they can’t achieve their goals, they can’t raise their voice, or they can’t express themselves through peaceful means, then they choose violent means. I don’t know whether it is legitimate or illegitimate, but yeah, people resort to such violence in such circumstances. That is what I have understood.

Even when I was reading Fanon, I was thinking about this Kashmir issue again. Because it is somewhat related to the situation in Algeria, right? Or even when I was watching the ‘Battle of Algeria movie, it was somewhat related. The same kind of violence, and harassment of the local population, happens as a daily affair in Kashmir. It also becomes sometimes like, when people get harassed, when you see your elders getting harassed by the security establishment, like when you can’t even move freely in your city, in your hometown, in your land, then some people do resort to violence. It further becomes an inspiration to other people. No one wants to live a humiliating life, right, no one wants their family or friends or relatives to get humiliated or getting tortured or anything. So the injustices by police are also one of the reasons.

So, I don’t see it as legitimate. Like I still see that the outcomes of any violent resistance do not do any good in the long term because it creates this culture of violence. But yeah, people do resort. Not everyone thinks the same, everyone has different viewpoints. I may think that it’s not good, but my brother may think that, yeah, it’s good, it’s justified because it is the only means we have, we don’t have any other opportunity. It varies, but yeah. When people are not given the opportunity, they sometimes resort to violence. Yeah. That would be all.

[1] Singh, Maj Gen Jagjit (2000), With Honour & Glory: Wars fought by India 1947-1999, Lancer Publishers, p. 18, ISBN 978-81-7062-109-6.

[2] Fareed, Rifat (2017, Nov 6), ‘The forgotten massacre that ignited the Kashmir dispute’, Aljazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/6/the-forgotten-massacre-that-ignited-the-kashmir-dispute.

[3] Jacob, Jayanth & Naqshbandi, Aurangzeb (2017, Sep 25), ‘41,000 deaths in 27 years: The anatomy of Kashmir militancy in numbers’, Hindustan Times, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/the- anatomy-of-kashmir-militancy-in-numbers/story-UncrzPTGhN22Uf1HHe64JJ.html.

[4] IndiaSpend (2019, Aug 2), ‘Pellet guns have killed 24, blinded 139 in Kashmir since 2010: Report’, Business Standard, https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/pellet-guns-have-killed-24- blinded-139-in-kashmir-since-2010-report-119080200151_1.html.

[5] Bhat Hibah (2020, Sep 22), ”We Are Sure They Have Him’: Enforced Disappearances Continue to Haunt Families in Kashmir’, The Wire, https://thewire.in/rights/kashmir-army-enforced-disappearances.

[6] Subramanian, Nirupama (2020, Jan 24), ‘Explained: The Kashmir Pandit tragedy’, The Indian Express, https:// indianexpress.com/article/explained/exodus-of-kashmiri-pandits-from-valley-6232410/.

Image credit Twitter

Image credit Twitter