by Noel Mariam George 6 February 2020

Who is a migrant? Such a seemingly simple question becomes more complex when there is no definition of a migrant that has complete legal acceptance in international law and has contested meanings in state law. However, despite contestations, the International Organisation of Migration under the UN Migration defines her/him in the following way- “a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons”. The migrant is often contrasted with the refugee, as one who has moved out of one’s country, often in search of economic opportunities by ‘choice’, in contrast to the refugee, who is pushed out or flees, due to persecution. Movement defined by choice is what differentiates the migrant and the refugee.

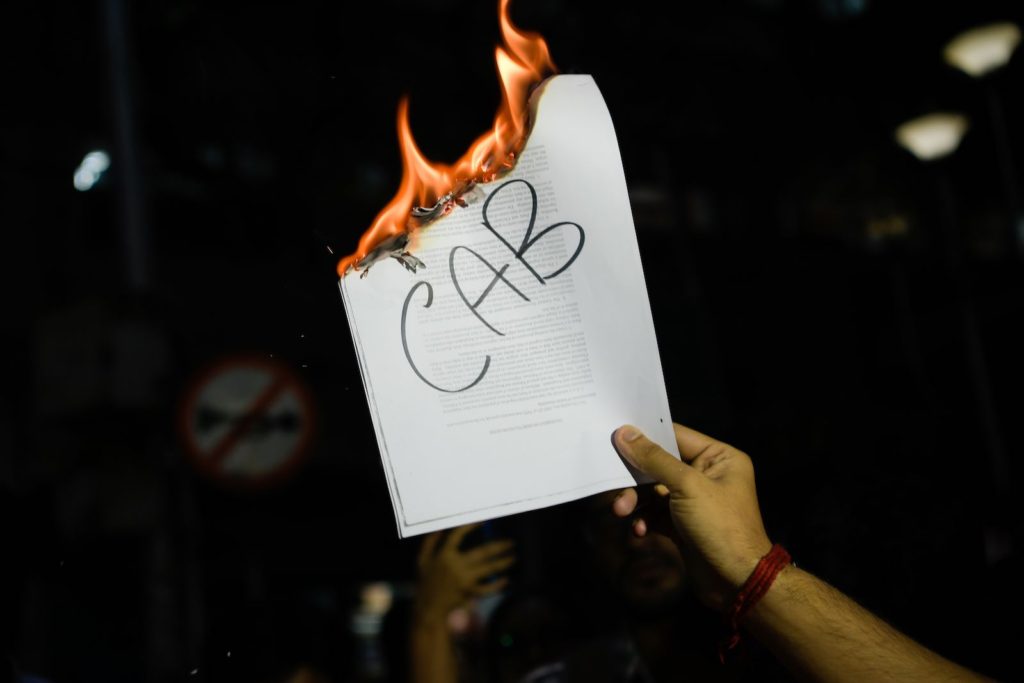

However in India, the new amendment by the government in Citizenship laws, combined with proposition of a National Register of Citizenship (NRC) introduces a semantic shift in the meaning of who a migrant or refugee is; as understood traditionally. Dominant scholarship in the light of protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act have pointed out on why the amendment is unconstitutional as per Article 14 of the Indian Constitution as it introduces an unequal classification in the provision of citizenship that would not fit the test of rationality and reasonableness. The Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, (CAA) has been critiqued by to be discriminatory along the lines of religion (as it excludes Muslims) and nationality (as it excludes ethnic minorities like Tibetans, Tamils and the Rohingya). However, such unequal classification is not new- the Overseas Citizens of India Cardholder or the OCI scheme of 2005 would also be an amendment that would fail article 14. However, if the question of constitutionality were the only test, how can we explain the massive, sustained, de-centred and yet networked protests in India today; especially amongst the Muslims of the country?

Such a question makes clear that what is at stake in India is much more than constitutionality in the largest struggle for equality post Independence. India is in the midst of a struggle that would redefine the republic in fundamental ways, and yet at the heart of it, is the spectre of the migrant. It is important to locate the semantic shift in the meaning of the migrant from being defined by ‘movement’ to being defined by ‘exclusion’ to understand the true essence of the protests. The migrant in India today- if the NRC is to be implemented would be defined in terms of exclusion- from the four axes along which citizenship is defined in modern democracies- politics, economics, law and territory. Defining the migrant in terms of exclusion makes clear that migrant is not an ‘outsider’, but probably an ‘insider’ who is not inscribed in the state because s/he lacks the documents as demanded by the state. It is no more a question of movement along borders that makes one illegal or a migrant, but a new understanding of illegality in which the legal as the binary of the illegal is defined through exclusion. Those most vulnerable to such exclusion would be the poor, illiterate, women (as women often move, post marriage and would not have documents to prove decent), landless and displaced people.

20th century was the century of the citizen in India, as decolonisation made millions of citizens out of politically excluded colonial subjects. Citizenship in India was defined in purely political terms as ‘all’ within the territorial expanse of India, irrespective of race, caste, gender, religion or region. However, if the NRC is to be implemented, the 21st century would be the century of the ‘migrant’, as the one defined by exclusion. Migrants would be the dispossessed who would be further dispossessed when marked- illegal or the non-citizen. It is important to notice the larger project of the NRC as a process that would ‘produce’ migrants, more than it would make citizens of people. The state would demand proof of citizenship to disenfranchise many into the category of non- citizen. Migrants would be reduced to a non political position as they would be stripped off the rights to vote and the right to have rights. It would further economic exclusion as their labour would be unpaid, or restricted to the informal economy; legal exclusion would be criminalisation often through laws of exception which surpass fundamental rights and finally territorial exclusion would imply that they do not have the right to own land and would even be confined into detention centres. From being defined by the choice to move, the migrant would be defined by restrictions on movement. In a country where the majority are poor, illiterate, landless and displaced- this would imply that the camp would emerge as large as the state itself. If the citizen was defined through inscription of rights and the ideas of equality, liberty and fraternity- the migrant would be a reduced category without rights, defined by confinement.

The figure of the migrant would redefine Indian political subject from the citizen to the reduced category of the migrant; however, when combined with the CAA it would also produce an exclusive category of Muslim migrants as the sole victims of detention and deportation. The new amendment to Citizenship –The Citizenship Amendment Act, combined with National Registry of Citizenship and National Population Register, would declare a legal apartheid with Muslims as secondary citizens. The International Criminal Court of the 2002 Rome Statute defines apartheid as a crime – “committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime”. While race in India cannot be understood in the traditional sense ; racialisation of Muslims force us to think about race in more complex terms beyond the essentialist biological discourse that it is has traditionally been understood as. The post colonial scholar Falguni Sheth redefines race in the following way – “Race, is a process embedded in a range of legal technologies that produce racialized populations who are divided against other groups”. Indian Muslims are subject to racism in India through legal processes that exclude them, arbitrarily, from the majority Hindu population. Along with the CAA, there have been several laws that have gone unnoticed that racialize Muslims in India.

There have been changes in legislation in the banking sector with regards to Non Resident Holdings (NROs) and Visa regulations that limit residence of ‘non-citizens’ that are discriminatory against Muslims. These changes have come along with of the abrogation of article 370- in a ‘disputed’ (as per international law) Muslim majority territory that legalised a settler colonial project in Kashmir. So, the Muslim protests in India are more than constitutionality and is more so, a struggle against the legalisation of an apartheid regime. It is then important to speak of legality beyond positivist state law and speak of legality enshrined in international law as natural rights of all humans. While we have an international discourse on the refugee, what we do not have is a discourse for this newly defined idea of the migrant and in India – the specific category of the Muslim migrant produced through legal changes that have institutionalised apartheid. It is important to make such a discourse as Migrant rights matter and more so, Muslim Migrant rights matter!

References

Chakrabarti, Ran ; Varghese, Sonu: 20 January 2016 ‘India: Amendments to The Citizenship Act, 1955 and The Concept of The Overseas Citizens of India Cardholder’, Indus law, Available at : http://www.mondaq.com/india/x/459548/general+immigration/Amendments+to+the+Citizenship+Act+1955+and+the+concept+of+the+Overseas+Citizens+of+India. Accessed on : 30. 01. 2020

Defining Apartheid as Crime. 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Available at https://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/EA9AEFF7-5752-4F84-BE94-0A655EB30E16/0/Rome_Statute_English.pdf . Accessed on 29.10.2020

Falguni Sheth. 2012. Towards a Political Philosophy of Race. SUNY Press: New York

Ministry of Home Affairs, Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) Cardholder, intro Available at http://mha1.nic.in/pdfs/intro.pdf

‘Parliament passes Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2015’, Ministry of home affairs answers questions on Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 Government of India Archives. Available at: https://hcikl.gov.in/pdf/press/CAA_2019_dec.pdf. Accessed on 30.01.2020

Section 5(1A) of the Indian Citizenship Act, 1955

‘Who is a Migrant?’ : International Organisation of Migration , United Nations. Available at: https://www.iom.int/who-is-a-migrant. Accessed on: 29. 01. 2020