by Amit Kumar and and Puja Pal

Indian economy has entered into major economic slowdown. The unemployment rate stood at four decades high at 6.5 % in 2017-18 as per PLFS. The joblessness for youth workers is also in double digits. The economic survey 2019-20 has suggested that in order to generate employment opportunities for India’s youth there is need to aggressively participate in the global value chains and networks. It also suggested that with the ongoing US-China trade war, the firms are looking for the opportunities to relocate their production to the low-cost countries and India should use this opportunity in its favour. It further claims that by integrating “assemble in India” with “make in India”, India will be able to generate 4 crores ‘Well-Paid Jobs’ by 2025 and 8 crore jobs by 2030.

Now a days the production is organised in the global vale chains or networks. In these value chains and networks, the production is organised and fragmented across the countries. This involves activities starting from the conception of the product, its design, production and distribution of the final product to the consumer. With the advancement in the ICT and reduction in the trade costs across the border has resulted into the restructuring of the production practices.

These value chains or networks are characterised by outsourcing production to the low-cost developing countries while the developed world retains the high value-added activities such as designing and marketing. This has resulted into increasing competition among the developing countries to participate in these networks or left behind in the race to generate more jobs and growth. Although there is no clear evidence that the participation in these global value chains or networks will able to generate ‘decent work’ defined by the ILO. The competitive pressure on the suppliers in terms of declining lead time (time to deliver products to the buyers) and the price squeeze (lower price) is forcing them to adopt non-standard forms of work. This also includes growing number of home-based workers (HBW) which can be hired or fired as per demand conditions. The home based workers are inserted into these value chains/networks through various kinds of sub-contracting arrangements.

These are the workers who work form their own home or the dwellings attached to their own homes. The home-based workers are generally of two type-Homeworkers/outworkers are the workers hired mostly indirectly by the firms through the contractors or subcontractors. In most cases they do not even know for whom they are working and are generally paid on a piece rate basis. The other category is own account workers who buys their own raw material and takes their final product to the market by themselves.

As of 2017-18, there are 30.1 million HBW in India (it was 23 million in 1999-00). The economic survey also lists industries which have potential for greater exports and job creation these are Textiles, Clothing, footwear and toys. According to the PLFS data[iv], textile and apparel are also the industries which together employs almost 50 percent of the HBWs. Given the focus of Government to participate further in the GVCs, it becomes important to see whether the home-based work is remunerative or not.

The latest data on the home-based workers can be obtained from the PLFS and it shows that more than 91 percent of the HBWs are self-employed (this includes own account workers, employers and helpers in the household enterprise). The share of casual workers within the HBWs has increased from 2.36 percent in 1999-00 to 5.91 percent in 2017-18.

Table 1: distribution of the HBWs according to the employment status

| Employment Status | 1999-00 | 2017-18 |

| Self-employed | 94.95 | 91.32 |

| Regular/salaried | 2.69 | 2.76 |

| Casual | 2.36 | 5.91 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: NSS 55th round & PLFS

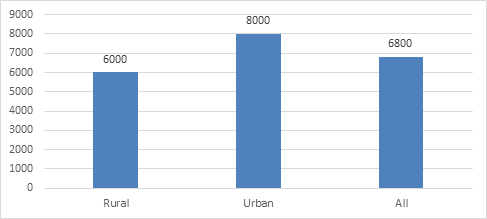

This is also the first time that we have information regarding the earnings of the self-employed workers along with other workers. The graph below shows the monthly median earnings of the self-employed HBWs. It shows that these workers are earning Rs 6800 on monthly basis. Although the earning in the rural areas are significantly lower than in the urban area i.e. Rs 6000 as compared to Rs 8000. These earning are significantly lower than what has been prescribed by the committees set up by government.

Figure 1: Earnings of the Self-employed Home Based Workers.

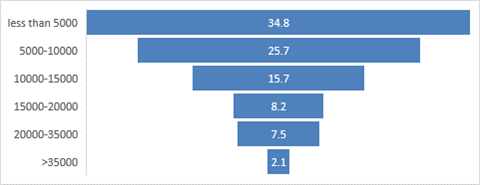

Around 35 percent of the workers are earning less than Rs 5000 per month and more than 77 percent of the workers are earning under Rs 15000 on monthly basis. If we compare these earnings with the minimum salary of Rs 18000 recommended by 7th finance commission then 89 percent of the HBWs are earning below this threshold. Recently, government constituted an Expert committee to determine minimum wages and it has recommended the minimum wages to be Rs 9752 irrespective of the sector, skill, and location the worker might be in. By taking this recent estimate as benchmark, then also 66.5 percent of these workers are not able to earn this much.

Figure 2: Percentage distribution of workers according to income

It is also argued that home-based work is preferred by female as it provides the flexibility to combine work with their household responsibilities. But at the same time the employers use the existing gendered norms to their benefit. This is clear from the fact that women HBWs are earning way less than their male counterpart. The median monthly earnings of the female workers are only Rs 2500 while that of male is Rs 9000 monthly.

Figure 3: Median Monthly Earnings across Gender

Male 9000

Female 2500

Along with the low wages the HBWs also suffer from uncertain working conditions, long working hours, serious health and occupational hazards. By employing HBWs the employer also avoids providing any kind of work-related benefits which could have been provided if they employ them in the factory settings. They do not get any kind of social security benefits. Given the fact that workplace is there home; they are invisible and the presence of the associations or organisation are also insignificant.

It is true that participation in the global value chains and network do provide employment opportunities but then it must also be asked whether these jobs are sufficiently remunerative let alone decent. Home based workers have been and are increasingly becoming part of the global value chains and networks. But they are situated at the lower rungs of these value chains and networks. The above analysis suggests that the claims made in the economic survey is not true particularly for the HBWs. The home-based workers are working poor who are unable to earn minimum wages even after working for long hours in poor working and living conditions. With greater emphasis of the government to integrate further these GVCs, there is urgent need to put required regulations in place to provide ‘Well-paid jobs’.

[iv] Calculated from unit level data