Britta Ohm, Université de Berne 14 May 2019

India votes until May 19, and Western media and opinion seem to be slowly waking up to the dangers faced by what is often hailed as “the world’s largest democracy” to constitutional guarantees.

Like in other cases of today’s right-wing and populist authoritarianisms around the world, these dangers are not completely new, even if they are rising in a particular fashion.

“Good days are coming”

The currently held general elections in India are seen by many as a watershed. Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has made his way over the past two decades from being the chief minister of the State of Gujarat, where the anti-Muslim pogrom of 2002 happened under his responsibility, to the prime minister’s office in New Delhi.

His first incumbency 2014-19 was won with an absolute majority of seats for the BJP coalition but only 31% of the actual vote (due to India’s first-past-the-post election system) and carried the slogan Achhe din aane waale hain (“Good days are coming”).

Modi’s supporters and the members of his government are now disputing in all available media whether the “good days” have arrived more for big industrialists rather than for starving farmers, oppressed Dalits and terrorised minorities, as the opposition tries to point out.

But these elections are not really about policy issues. Instead, they have zeroed in on the person and leadership of Narendra Modi, and with him on the legitimacy of Hindutva (Hindu-ness) as India’s new dominant ideology.

Read more: Politics of Hindu nationalism: India Tomorrow part 2 podcast transcript

Identification with the country

Narendra Modi’s trajectory from “good days for all” into an extremely personalised election campaign has palpable parallels in the path that Indira Gandhi of the Congress Party travelled in the 1970s. Her famous call Garibi Hatao! (“Erase poverty!”) soon became reduced to her very identification with the country in the slogan “India is Indira, Indira is India”.

In both cases, the initial, apparently democratic promise carried within it the future damage to democracy, because its utopianism barely concealed the priority of claiming power.

In Gandhi’s case, democracy was eventually suspended during “the emergency”, the phase of open authoritarianism 1975-77, with which she hoped to consolidate her rule but which propelled her out of power when she finally held elections.

In Modi’s case, one could ask – as critical activists have done – if an “emergency” is yet to come or if it is already taking place in other forms.

CLICK to hear Indira Gandhi’s speech during “the emergency” (1975).

Shifting modes of controlling the media

Rather than simply censoring and shutting down media and jailing journalists, as Mrs. Gandhi did, Modi performs a three-dimensional dance with different media, so to speak.

First, he disables uncontrollable questions and unpleasant images of himself by outright refusing to speak to the press or by demanding the questions ahead. Press conferences with the prime minister, once a norm, were terminated immediately when Modi took power in 2014.

Second, he maintains a pronounced silence not only on vigilante, social media–circulated violence, particularly against Muslims, but also on organised hate campaigns and physical attacks against journalists. Among many others, the most prominent example was the murder of Gauri Lankesh in Bangalore.

Consequently, Modi’s ever-growing media presence has been shifted into the sphere of mass-event management and image production, supportive TV networks and personalised platform media, including Modi’s own Internet stream and the controversial NaMo TV, which was launched ahead of the current elections, apparently without any licence.

Newslaundry analyses the new channel NaMo TV.

In a dual mode of immediacy – through online addressability and especially though his mediated presence at countless mass rallies all over India – Modi ensures a direct and unfiltered contact with “the people” that has largely replaced representative mechanisms of government.

On the other hand, his main institutional reference is the non-mandated Hindu-nationalist core organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which shapes and connects countless affiliated outfits – the so-called Sangh Parivar (‘family of organisations’) – across India and also well beyond.

This indicates a dimension of organisation beyond established state structures that Indira Gandhi never quite commanded.

What we mean by democracy

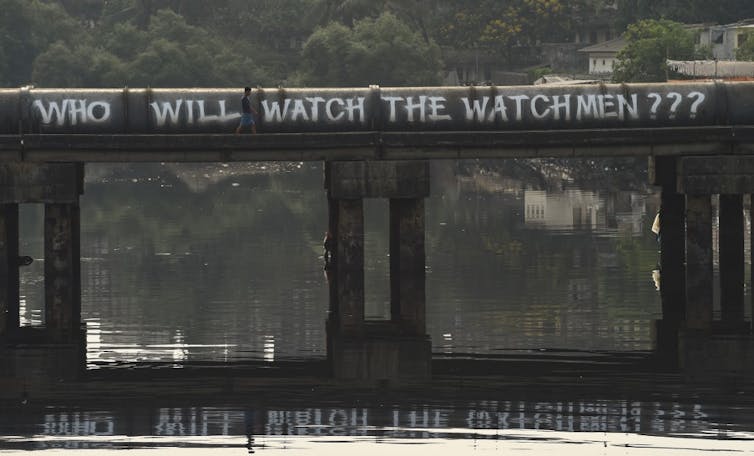

It would thus be misleading, as is common in the media coverage of various right-wing populisms, to merely focus on Modi as a direct threat to democracy. Instead, it has become important to ask what we mean by democracy, not only in post-colonial countries such as India.

It is crucial to remember that since the 1980s, the Hindutva movement rode on a wave of evolving media and technology as much as of democratic criticism against a liberal democracy that acted in the interests of privileged elites (chiefly embodied by the Nehru-Gandhi family).

Hindutva thus appropriated popular urges for the democratisation of an often self-serving and benevolent established democracy. Especially with the neo-liberalisation of the economy came growing demands for wider political participation and access to both material and immaterial resources. It is this “democratisation of democracy” that has turned visibly toxic, along with the masculinity it celebrates, in Modi’s populism.

Other current political strongmen, from Trump to Erdoğan, feature a similar toxicity. It is important to keep in mind, however, that Modi’s variant is ideologically rooted in the history of fascism.

The long road of fascism

Modi himself comes from the fold of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the National Corps of Volunteers. The RSS was founded in 1925, at the same time as fascist organisations in Germany, Italy and Japan.

Modi is a pracharak, an unmarried full-time volunteer of the RSS. While he admitted in 2014 that he was married when he was younger, he appears today as a “bachelor” who remains faithful to his duty, “serving” the country. He swore an oath to the RSS basic ideology of a Hindu rashtra (Land of Hindus), which clearly understands “Hindu” in terms of race, blood and soil.

After BJP’s former leader A.B. Vajpayee (1998-2004), Modi was the second pracharak to become India’s prime minister, but the first with such a nominal majority of votes and such a devoted and active following.

Different from their European and Japanese equivalents, the RSS and the Sangh Parivar have now spent, largely without interruption, almost a century violently working themselves through India’s diversity and democratic structures.

A wide network of influence

On the way, they could built operative networks in both state and private institutions, ranging from the police and army to the judiciary, academia and media. Moreover, they have established their own organisations for many societal groups, including students, women, workers, peasants, Adivasis (India’s indigenous populations) and even Muslims. In addition to setting up professional, welfare and religious associations, they also run the largest private education networks in India.

Not least, they have consistently recruited large numbers especially of young unemployed or underemployed men for the “defence of Hinduism” in paramilitary groups such as the Bajrang Dal (Hanuman’s Force). They are notorious for their organised violence against minorities and dissenters. Over the past few years they have also been trained in the use of firearms.

Pracharak Modi and his professionally agitated supporters are not likely to take losses in these elections lightly. That possibility implies a threat of further violence which might already have motivated a fair number of votes in Modi’s favour. The failure of building a powerful opposing coalition, on the other hand, and the grandchildren of Indira Gandhi yet again being put up as the main alternative, have made the space for voters between a rock and a hard place narrower than ever before.

Britta Ohm, Associate Researcher, Institute of Social Anthropology, Université de Berne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.