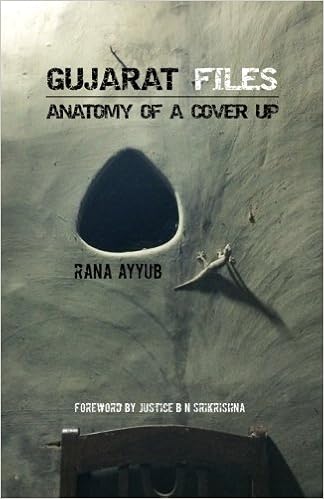

Author: Rana Ayyub, self-published, 2016, Paperback, 204 pages

Modi, a Hindu nationalist, was then chief minister of Gujurat as he had been in 2002 when three days of communal riots in the province had taken at least 1,000 lives, Hindu and Muslim, but many more Muslims. Critics accused Modi of inciting the killings by urging authorities at a February 27 meeting to “go slow” in controlling the riots. A charge never proved but reliable enough that the United States refused Modi a visa to visit the country.

Ayyub’s reputation as an investigator was then riding high. Her undercover sting operation had helped jail Amit Shah, who had held 12 portfolios in Modu’s provincial cabinet. Shah was released after a few weeks in jail. Under Modi now as India’s prime minister, Shah is the central government home minister and close enough to Modi to be called India’s “invisible prime minister.”

For anyone interested in becoming an investigative reporter, Ayyub’s experience is a textbook example, although many journalists would consider hiding or falsifying an identity unprofessional. She wheedled her way into lengthy, secretly recorded interviews with top officials connected to the riots.

Her initial interview was with a retired official, Ashok Narayan, who was the Gujurat home minister when the rioting broke out.

“You must have gone red in the face when the Chief Minister asked you to go slow,” Ayyub stated in opening their conversation, referring to the February meeting.

“He would never do that,” responded Narayan. “He would also never write anything on paper. He had his people and through them….it would trickle down through informal channels to the lower rung police inspectors.”

“And there is no proof for inquiry commissions,” she said. “Precisely,” said Narayan.

Later in the conversation, she tried again: “But he asked people to go slow,” Ayyub said to Narayan.

“He would not say that in the meeting,” said Narayan. “He would say that to his men.”

In her looking back at the interview, Ayyub concludes about Narayan, “He….at no point suggests the CM (chief minister) gave marching orders against Muslims”.

Through Narayan, she managed in her filmmaker role three meetings with a reclusive, tight-lipped K. Chakravarty, who was head of Gujurat police during the riots, now retired in Mumbai.

“Did he give orders not to act?” she asked Chakravarty, who attended the February meeting with Modi.

“They didn’t give any illegal orders to me,” said Chakravarty. “….it will be on a one-on-one basis, not in front of 20 people…”

In a footnote, Ayyud concludes, “From various versions that I gathered during the sting operation, nothing suggests that Modi gave an order of this nature ….what Chakravarty and Narayan both said was that orders were given to individual state officials.”

In her pose as a woman making a film about Gujurat to show to the Gujarati community in the United States, Ayyub wangled a 30-minute meeting with Modi. He showed her books by Barack Obama and told her how much he admired the American president. He then sent her to an aide to get promotional material about Gujurat. She never confronted him about the February 27 meeting or an order to “go slow” in ending the riots.

Ayyub said she wore her wristwatch camera and recorder, but the reader gets no verbatim of her conversation with Modi. She showed the interview to her editors at the publication, Tehelka, celebrated in India for its sting operations.

“Modi is all set to be the most powerful man, the PM (prime minister),” an editor tells Ayyub. “If we touch him, we will be finished.”

After at least eight months undercover, the editors decided that Ayyub had not found a smoking gun pointed at Modi, nor did she have Modi on tape confessing to giving orders to go slow. They killed the story.

Offered a second meeting with Modi, she made an excuse and turned down the invitation.

“I have remained silent,” Ayyub ends her account. “Until now.”

She self-published her book, much of it taken up with lengthy verbatim interviews, not only with Narayan and Chakravarty but others involved in the Gujurat rioting and politics. Readers have an opportunity to judge for themselves how she carried out an attempted sting.

The book has sold more than 600,000 copies and has been translated into 13 languages, including Hindi spoken widely in India. She has earned many international awards for her journalism. Dexter Filkins wrote a lengthy, favorable profile of her for The New Yorker. Ayyub eventually left Tehelka. She now writes mostly for foreign publications, and under Modi’s administration is mainly shut out in India.