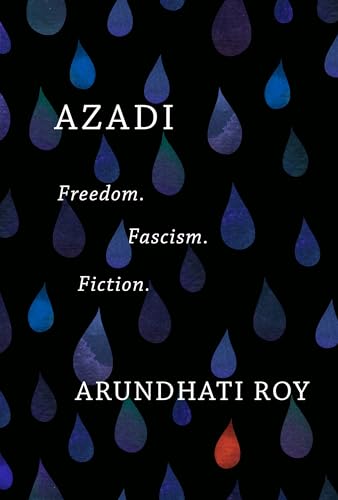

Haymarket Books, Chicago, Illinois, USA, 2022, Paperback, 307 pages, $19.95, ISBN: 978-1-64259-706-6

By Arnold Zeitlin 22 June 2022

Running like a thread through this collection of lectures, award speeches, opinion articles and just plain published rants is novelist Arundhati Roy’s anger. The principal target of her anger is Narendra Modi. India’s prime minister. Others are his political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP); the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh(RSS), the Hindu nationalist movement which spawned the BJP; Amit Shah, the home minister in Modi’s cabinet; Yogi Adityanath, the Hindu nationalist chief minister of the state of Uttar Pradesh; the police and established authority in general; and a variety of legislative and executive actions that make life harder for Kashmiris and other Indian Moslems. She conflates Hindu nationalism with fascism.

Most of her writing in this book appeared between 2018 and April of 2020, “two years,” she writes, ” that in India have felt like two hundred.” Roy’s fiction occasionally lapses into obscurantism ( her novel, The God of Small Things, won the 1997 Man Booker prize for fiction) but here she writes with cogent clarity that makes for sharply persuasive advocacy.

As for Modi, after he imposed with four-hours notice an all-India lockdown against the Covid-19 virus in March 2020, Roy writes “the prime minister thinks of citizens as a hostile force that needs to be ambushed, taken by surprise but never trusted….India revealed herself in all her shame — her brutal, structural, social and economic equality, her callous indifference to suffering.”

Roy ends this collection with a plea for Modi to resign. “I beseech you, step down,” she writes. “….You have forfeited the moral right to be our prime minister….There are many in your party who can take your place….”

She suggests a new government with a virus crisis management committee that includes the opposition Congress party, representatives of states’ parties and public health expects. “You may not understand this,” she says, directing her message at Modi. ” but this is what is known as democracy.”

Roy is deeply troubled by the Modi government’s ending the special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir, dividing it into two Union territories, imposing what she labels as a “digital siege” that cut telephone and internet service and isolated the territories from the rest of India and the world and continued their heavily armed occupation. Also troubling her is a series of Modi government actions that seem designed to strip citizenship from undocumented and often the poorest Indians and make life even harder for the country’s Moslem population.

“In India today,” Roy writes, “a shadow world is creeping on to us in broad daylight….India isn’t by any means the worst, or most dangerous place in the world, at east not yet, but perhaps the divergence between what it could have been and what it has become makes it the most tragic.”

Her “most tragic” India doesn’t have the economic and social promise that many other observers see but it does have its heroes. An example is B.R. Ambedkar, the late Dalit leader, who, she notes, wrote India’s so-called secular constitution in English (as she has written her novels). Her most fetching article in this collection is a 2018 lecture about language, including her distress at the separate scripts for Urdu and Hindi and the making of Urdu into a Moslem language.

Roy’s anger focusses in Azadi on the dark side of the Indian experience at a time when so many others hope to see the country emerge as a world power, not so much as to indict her homeland but, perhaps, to help it see the way to light.