Emerging from the village to mark a new country on the map

Very few people in history can be credited with accomplishing what Mujib has accomplished. Yet many students of world history know very little of this larger-than-life figure. It is an unfortunate fact of history that the life and work of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman are little known outside Bangladesh. His ideas and legacies should be debated and discussed in an open manner. As a historical figure, he deserves wider recognition.

To start knowing Mujib, it is important to know one thing: he was more than a politician; he was someone who was able to inspire a nation to make a fresh mark on the world map.

Mujib led the struggle for a democratic alternative to military rule, and subsequently for the independence of Bangladesh. In this, the challenges were perhaps greater than they were for most leaders of the other new nations of Asia and the rest of the global South.

Mujib’s historic speech on 7 March 1971 at the Racecourse was heard by more people than heard Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. And his readiness to make great personal sacrifices – 12 out of 24 years of undivided Pakistan he spent in prison, facing the gallows twice – puts him up there with the likes of Nelson Mandela.

Mujib was not just a politician: he became the father of a nation. He stood out among many other important leaders in several unique ways. For starters, he was not from an elite background. He was born in a village in 1920, son of a small-town court record-keeper in eastern Bengal. As a 20-year old student in 1940 at a college in Kolkata, he joined the movement for Pakistan. At the age of 23, while still a young student, he had gathered the political experience to get elected to the municipal council.

Later, while studying law in Dhaka (then the largest city in predominantly Muslim eastern Bengal), he founded the Muslim Students League. He also joined the Bengali language movement, resisting the imposition of Urdu as the main language of Pakistan – a language that most Bengalis did not understand. And this despite the fact that move of Pakistan’s population lived in East Pakistan: 56%, compared with 44% in West Pakistan. In short, the majority in Pakistan were Bengalis. This did not seem fair to Mujib but was only the first in a series of unfair things yet to come.

Mujib’s campaigning in the language movement led him to be arrested twice by the newly independent Pakistani government in 1947. Two arrests within six months. After his release, in 1949 he led a strike of the lowest-paid workers of Dhaka University, staging a sit-in at the vice chancellor’s residence. Mujib’s struggle for social justice for the poor makes him extraordinary among nation-builders.

After the sit-in, Mujib was again arrested. While he was in prison, a new political party, East Pakistan Awami Muslim League, was formed. Mujib was made Party Secretary while he was behind bars.

Mujib was released after a short while. Soon after this, he started protesting again. In particular, he led a movement protesting the food crisis in East Pakistan and was imprisoned a few times thereafter. All told, he was imprisoned five times by the Pakistani government between 1948 and 1949. Overall, Mujib was arrested at least 22 times in his life as a result of his campaigning – a strong reminder of the personal sacrifices he was prepared to make.

A rounded leader

In 1953, Mujib was elected General Secretary of the Awami Muslim League. At the first provincial elections in 1954, a united front with which his party was allied, won all seats in East Pakistan. Mujib was made a minister in the provincial government at the age of 34. Around the same time, he was re-elected as the top official of his party. Mujib’s core leadership qualities thus started to emerge:

- In 1955, to stress his commitment to secularism and his openness to all residents of east Bengal, including the large Hindu minority (some 20% at the time), his party dropped the word ‘Muslim’ from its name, to become simply the ‘Awami League’. Mujib was not a narrow ethnic nationalist. Another rare characteristic for the creator of a new nation: he was an open-minded secularist.

- In 1956, he resigned as minister to focus full time on his role as general secretary of the party, building the party organisation. Mujib knew that his party needed a strong structure, one that would go beyond one-man rule. This, again, made him unlike many other nation-builders: Mujib did not allow his personal ambition to overcome the need for strong organisation. As a result, Awami League then, and for a long time thereafter, was characterised by a solid structure capable of carrying out its mandate for the people and governing effectively. In this endeavour, Mujib understood the importance of mobilising the smallest villages and towns.

- As well as being a strong campaigner, Mujib was a flexible leader – yet another unusual characteristic at the time. He was open to negotiation at even the slightest hint of an opportunity to make progress in this way. In 1957, Mujib – the firebrand charged with the organisation of the Awami League – was reputed to be composed and helpful to his political advisories, including the then governor general of Pakistan. Mujib was showing that he was not just a hard-headed agitator but a mature and rounded leader, seeking moderation.

Post-1957, in fact, Mujib felt the time was right to adopt a moderate position, to see if progress was possible with the West Pakistanis. At the same time, though, he knew there might come a time when defiance and resistance would be necessary. He understood that, in politics, timing is extremely important. And indeed, at this point, Mujib quickly learnt that progress through negotiations was not possible. The powerful elites in West Pakistan were not sincere about compromise with the majority of their own compatriots – the Bengalis. This minority dominated the armed forces of Pakistan, along with the higher echelons of the civil service and the main businesses. A huge portion of the earnings from exports from East Pakistan, especially of jute (the dominant export commodity), went to West Pakistan. Living standards were higher in West Pakistan. These injustices led Mujib to turn to defiance.

In 1958, army rule, or martial law, was imposed. Soon afterwards, Mujib was imprisoned for three years on trumped-up charges. In 1961, he was released, and he immediately started building a horizontal Awami League organisation – which was essentially an underground activity at the time. As a result, in 1962 he was imprisoned again.

Most fathers of new nations did not face such serial jailing. Throughout his life, Mujib was in jail 22 times, perhaps a record!

“We mustn’t be swayed by populism if we are to build for Bengal a better future. Narrow parochialism will set us back a thousand years” – Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1892-1963).

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy’s role in the Subcontinent’s political history is unparalleled. In his 43-year long political career, he achieved many milestones: one of the first Indians to graduate with a BCL degree from Oxford, among the first Indians to be called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, first Muslim deputy-mayor of Kolkata, Chief Minister of East Bengal, leader of the United Bengal Movement, fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan, founding-member of the Awami League, etc.

Weary of the dangers of communalism, Suhrawardy spent a lifetime fighting for Bengal’s territorial integrity and political unity in an era of widespread division. Enamored by the politics of C.R. Das, he embraced the Bengali nationalist cause as early as 1947, leading the United Bengal Movement which could have reshaped the Subcontinent’s history. Following Partition, Suhrawardy realigned his politics to promoting Bengalis’ rights within Pakistan’s federal framework. Under his leadership, the United Front won a landslide majority in the 1954 elections. As Prime Minister, Suhrawardy committed to liberalizing Pakistan’s economy and modernizing its foreign policy. His example would inspire a generation of leaders including Begum Shaista Ikramullah, Kamal Hossain, Tajuddin Ahmad and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Ousted from prime ministership by West Pakistan’s military junta, Suhrawardy was exiled and died in Beirut in 1963. His body was brought back to Dhaka, where he is buried. Following Bangladesh’s independence, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman asked that the Ramna Racecourse, where he delivered his famous March 7th speech, be renamed the “Suhrawardy Udyan” after his old mentor. Of Suhrawardy’s role in the Subcontinent’s politics, journalist Syed Badrul Ahsan wrote: “Suhrawardy was a complex personality. And he was a formidable politician. Not until the rise of his protégé Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would Pakistan – and then Bangladesh- find itself dominated by a larger than life political figure.” | Photo: Dawn Archives.

A breakthrough for Mujib

In 1968, a major legal case, the Agartala Conspiracy Case, was brought against Mujib and some of his allies. The Pakistani authorities accused Mujib and others of conspiring with India to break with Pakistan. This was simply not true but the charges that Mujib faced carried the death penalty. Mujib was named as the main accused; in fact, these charges indicated that the West Pakistani leaders saw Mujib as the leader of the Bengalis. However, the military regime soon broke down under the force of widespread protests – especially in East Pakistan. Mujib was released in 1969 and the charges were dropped.

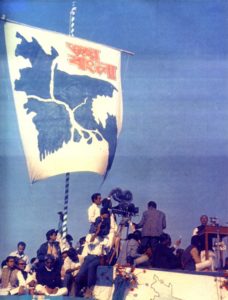

Mujib was immediately taken to the Racecourse – a major location for public mobilisation in Dhaka – and made a defiant speech before a vast crowd. It was there that he was given the honorific title ‘Bangabandhu’, meaning ‘friend of the Bengalis’. Notably, Mujib earned a revered title as living legend, similar to Nelson Mandela’s “Madiba” or MK Gandhi’s “Mahatma.”

In December 1970, the Pakistani military regime was compelled to hold the first genuine national elections of an undivided Pakistan. Of the 169 seats in East Pakistan, Mujib’s Awami League won all but 2. This gave the Mujib-led Awami League the majority of the seats in the new national parliament of Pakistan.

The military leaders and the powerful elites in West Pakistan had not anticipated such a landslide. They had believed that several different parties would win seats in East Pakistan, with the Bengalis splitting their vote and ensuring continued West Pakistani control. Now they found themselves facing the prospect of the Awami League actually ruling the whole of Pakistan. The military leaders thus decided to postpone the sitting of the new parliament.

Mujib, who had just attained the position of prime minister, responded to this by calling East Pakistan to participate in a non-cooperation movement. This meant that his party, the Awami League, could holistically and peacefully take control over the administration of East Pakistan. He thus became the de facto head of government in East Pakistan. As a result of his track record and his persuasiveness, the civil service, the police, businesses, the banks and the entire labour force (workers and farmers) followed his instruction. Mujib was in control!

Disclaimer: the army units were not under his control.

West Pakistani leaders used this time to strengthen the army and introduce more weaponry. Mujib needed to response to this new tense situation. On 7 March 1971, again before a huge crowd at the Dhaka Racecourse, he made the speech of his life! Such a speech that the United Nations has listed it as a cultural and political milestone, giving it international legendary status. The speech recalled the damage of earlier military actions by West Pakistan and rallied the crowd repeatedly. Then he said the words of his life: ‘The struggle this time is for our independence.’

Mujib shrewdly did not declare independence on that day because he had been informed that, if he did, the Pakistani airforce had orders to bomb the meeting of millions of people. Mujib wanted to avoid widespread violence in the pursuit of independence. He thus addressed the Pakistani armed forces: ‘Do not make this country a hell and destroy it. If we can solve things in a peaceful manner, we can at least live as brothers.’ The speech was a masterstroke!

Bangladesh in the making

After the speech of 7 March 1971, Mujib participated in extensive talks with Pakistani leaders, including the military dictator of the country, Yahya Khan, and Zulfiqar Ali Bhuttu, who was the most popular politician in West Pakistan (but had fewer parliamentary seats than Mujib). Mujib quickly learnt that the West Pakistani leaders were not negotiating in good faith, and in fact were using the period of the talks to prepare the military for a crackdown. This came on 25 March.

Mujib urged other Awami League leaders to go into hiding, so that the organisation would not be decapitated. However, on the night of 25 March, at great risk to himself, Mujib remained in his house and awaited arrest. He did not go into hiding but offered himself up, to minimise the destruction. He felt that the military might find it impossible to subdue the Bengalis, who were wide awake and ready to struggle. Thus, it was important that they had Mujib in their grasp. In this way, he was prepared to sacrifice his life. Mujib said at the time:

‘If the Pakistani military ruler thinks he can crush the movement by killing me, then he is seriously mistaken. An independent Bangladesh will be built on my grave.’

Mujib was arrested in his home, flown to West Pakistan and put in prison. The West Pakistani authorities put him on trial for treason. After a speedy trial, he was convicted and sentenced to death. Meanwhile, the Pakistani army unleashed a brutal campaign to subdue the Bengalis, massacring Bengali police, Bengali army officials who had defected, Bengali students, Bengali intellectuals and other civilians. This campaign is now known as an act of genocide.

Nevertheless, it was impossible to overcome the Bengali resistance. A war of liberation followed. Over the next nine months, with limited arms and resources, Bengalis successfully resisted the Pakistani military. Eventually, at the beginning of December 1971, the Indian army joined the Bengali liberation force. On 16 December 1971, the Pakistani army surrendered.

Mujib’s death sentence was delayed, and on 8 January 1972 he was released. He arrived in Dhaka on 10 January 1972, to become the leader and the father of a new nation – Bangladesh. Later within 1972, Mujib introduced a new constitution. The next year, an election gave the Mujib-led Awami League a landslide victory in Bangladesh.

Fathering a nation takes rigor

It was not easy to govern this new nation. Bangladesh had been badly ravaged by the war. It was also arguably the poorest country in the world at the time. Many of the leading Bengalis who might have helped rebuild had been murdered. Reviving the economy and restoring law and order represented a challenge on multiple fronts. In the context of the Cold War, Prime Minister Mujib started a series of bold diplomatic efforts to normalise relationships with all countries of the world. He also initiated a series of policy and relief initiatives. Meanwhile, quarters in the military establishment plotted to oust him.

Mujib’s nation-building was cut short before he could serve a full term in government. On 15 August 1975, a group of conspiring middle-ranking soldiers, backed by Pakistani era vested interest groups, staged a military coup and murdered Mujib and 16 of his family members, including children. Only two of his children survived, as they were not in the country at the time.

Under Hasina, the Awami League came to power four times, the longest administrative timespan in Bangladesh of any single party. The current Awami League government’s track record has become an exemplary development success story, which other countries can learn from.

Mujib’s account is a reminder that Bangladesh should be a country for focus, for so many across the globe. As Bangladesh makes its deep marks on the world economy, Mujib’s legacy as a unique father of the nation will without a shadow of a doubt grow. The popular cries of ‘Joy Bangla, Joy Bangabandhu’ (‘Long Live the Spirit of Bengalis, Long Live the Friend of Bengalis’) from the Mujib era will forever ring for the Bengalis. And Mujib’s values of fierce pluralism and social justice for the downtrodden live today as an exemplary motivation for generations to come.