Where there are waves, there must be retreats, writes William Milam

by William MilamMarch 22, 2019

Two Swedish political scientists have just published a fascinating study of the continuing growth of authoritarianism, which seems to have been renamed “autocratization.” Google defines autocratization as the reverse of democratization, i.e. going from a democratic political system or some reasonable facsimile thereof, to an authoritarian/autocratic one. On the other hand, my computer tells me autocratization is not a word in the English language. Well, English word or not, this study will soon become required reading in South Asia.

Political scientist Samuel Huntington popularized the idea that three waves of democratization had taken place in the modern world since about 1800, in his 1991 bookThe Third Wave of Democracy. Huntington is, perhaps, better known for his 1993 theory of the “Clash of Civilizations,” a concept misused frequently in the past two decades by those in the West trying to stoke hatred of the Muslim World. But his wave theory will have much longer lasting and more positive effects on our view of politics. According to Huntington, the first period of modern democratization began in the early 19th century when Jacksonian Democracy in the US extended suffrage to almost all white males in the country. This wave continued slowly until 1922, according to Huntington, lasting almost 100 years, and ended when Benito Mussolini reversed the trend by grabbing full power in Italy. At its height, Huntington wrote, 29 countries were full democracies. The second wave, he found, began soon after World War II ended and carried on for about 15 years until about 1962. As it ended, some 36 countries were democracies. Huntington counts the 1974 revolution in Portugal as marking the beginning of the third wave and it seems to have ended in the 1990s, not too long after he published his book. By some estimates, there were over 100 democracies by the mid-1990s, when this wave peaked, but I suspect this count was pretty generous and included countries that appeared to be on the path to democracy – were democratizing, in other words – but in which the institutions that serve as guardrails for real democracies had not matured and accrued the power to resist power-hungry leaders who sought it.

And where there are waves, there must be retreats. Is there in politics some principle akin to Newton’s Third Law of Motion? If there is it would read, “to every political action there is always a reaction, but this reaction is not necessarily equal to original action.” The Swedish political scientists I mentioned at the beginning have taken up the subject of democracy’s retreats (I will use their term from here on, autocratization) and provided us with much to ponder about the cause, the duration and most importantly, the inevitability of democratic decline. Let me state early in this piece that they draw very worrisome conclusions from their excellent study of the third wave of autocratization. First, as opposed to the first two waves of autocratization, very few of the autocratizing countries in the third wave have stopped short of full-blown electoral autocracy, yet few move to the ultimate, closed autocracy, to join North Korea and the small minority of closed autocracies. Second, the third wave, which their data shows began in 1993, has primarily affected democracies, unlike the first wave in which some countries affected were democracies and some were already-autocratic counties and the second wave which affected only former autocracies.

Third, the current wave of autocratization is much more gradual and led mainly by incumbent leaders and governments who came to power legally, usually by free and fair elections, and take full power in more informal and clandestine ways by undermining institutions, taking out opposition, muzzling the media, etc. The days of military coups and other sudden illegal power grabs have largely disappeared. And the autocratizers of the first two waves solidified their power grabs usually by rewriting constitutions to accommodate their predation, dissolving parliaments, and other blatant changes. The much more gradual rate of change toward autocracy in the third wave allows autocratic leaders to make autocratizing changes slowly and to erode the democratic institutions without drawing the world’s notice much of the time; multiparty elections are held regularly but without the institutions to guarantee they be free and fair they are merely a chimera.

How does one define real democracy? The authors base their definition on the definition of democracy by another well-known American political scientist, Robert Dahl, whose one-word term for his more complicated definition was “polyarchy,” meaning literally many rulers. They define the essential qualities of Dahl’s democracy—those things that make it a real democracy—and not something short of full democracy as: regular free and fair elections; an elected executive and legislature, complete freedom of association, universal suffrage, freedom of expression and alternative sources of information. These are chosen because they are measurable. But the data the authors mine to form judgements of the beginnings, endings, makeup, and characteristics of the waves of democratization or the reverse waves of autocratization is dependent on data being available on these essential qualities. Their study, therefore does not go back beyond 1900. And for the most part, their findings bear out Huntington’s as to pace and direction of both democratization up to and essentially through the third wave.

But it is their study of the third wave of autocratization that adds much that is new to our understanding of what is now called the decline of democracy. The conclusions I mention above are new and powerful insights to a phenomenon we are witnessing in our own time but not fully understanding. These conclusions show, for example, that comparisons with the earlier wave of autocratization are not as useful and we had thought. The tendency of contemporary democracies to erode gradually rather than to breakdown suddenly through coup d’etats or the like changes the way remaining democracies have to look at the situation. Identifying autocratization early, given the almost clandestine methods that have been adopted to achieve authoritarian governance, is doubly difficult. Knowing when democracy ends and autocracy takes over given the subterfuge and clandestine ways in which democracy is now undermined is, among other things, fairly subjective. There is no proven or agreed method of measurement. And the information collected on countries in the process of autocratization is often out of date and incomplete.

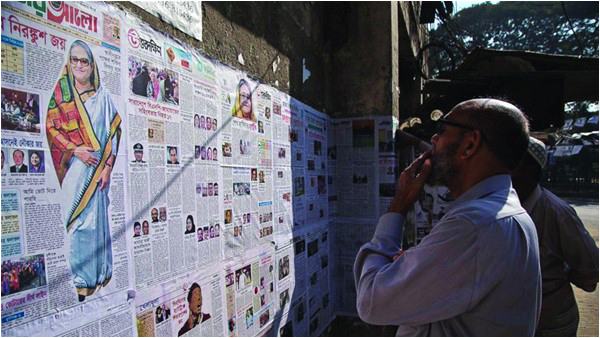

For Bangladesh, the issue is easily obscured by its great success in economic management and social development. When I raised the issue of Bangladesh’s growing authoritarian approach at a conference at Ditchley three years ago, I was practically shouted down by a room of so-called South Asian experts, who uniformly said, “But that can’t be, they are doing so well.” One long-time friend, who knows Bangladesh from the 1970s, said to me, “I hope you are wrong.” But I wasn’t. Much of the misunderstanding is because of the information lag. Even now, Freedom House, which grades most countries of the world as to their democratic credentials, grades Bangladesh as “partly free,” giving it an overall numerical score of 41 (100 is perfect) and on each of the categories of democracy, freedom of speech and association, political rights, and civil liberties, is graded at 5/7 (seven is the bottom).

But Bangladesh may be already in the “lost cause” category, an electoral autocracy. Did it not seal its fate by reaching back into the previous waves for its illegal power grab—the stolen election in which it won 96 percent of the parliamentary seats through massive cheating? As the authors of this study point out, most contemporary studies have approached the issue of autocratization as a binary process – a country is not an autocracy until democracy has completely broken down and it has entered the ranks of the closed autocracies. In fact, there is a continuum and because of the subversion of the institutions and the norms and standards of democracy that now typifies autocratization, many countries hover in the fringes of autocratic rule. Once they have turned out the lights of freedom on their people, it could be for a very long time. The question only Bangladeshis can answer is whether Bangladesh reached that point on the continuum via its long jump stolen election.

The writer is an American diplomat and Senior Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

The article was published in The Friday Times on 22 March 2019