BBC News 13 August

Indian-administered Kashmir has been under an unprecedented lockdown since last week after India revoked Article 370, a constitutional provision granting the region special status. Sumantra Bose, professor of international and comparative politics at the London School of Economics (LSE), explains why the decision is fraught with challenges.

At the end of October, Jammu and Kashmir will cease to be a state of India.

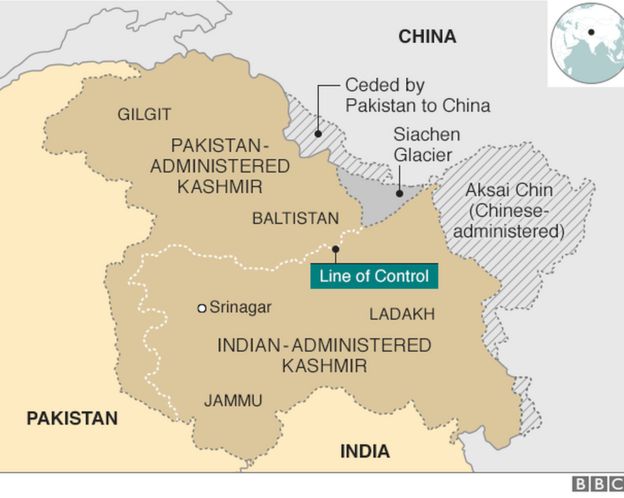

Last week, India’s parliament approved by a large majority the decision by the federal government to split the state into two union territories – Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. Union territories have much less autonomy from the federal government than states do, and are essentially subject to Delhi’s direct rule.

Almost 98% of the erstwhile state’s population will be in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, comprising two regions – the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley, which has about eight million people, and the Hindu-majority Jammu, which has about six million. The third region, the newly created union territory of Ladakh, is a high-altitude desert inhabited by 300,000 people, with almost equal numbers of Muslims and Buddhists.

Last week’s events fulfilled a Hindu nationalist demand dating back to the early 1950s: the abrogation of Article 370.

- Inside Kashmir’s lockdown: ‘Even I will pick up a gun’

- What happened with Kashmir and why it matters

- ‘India has betrayed Kashmir’

Hindu nationalists have for seven decades vehemently denounced Article 370 as an example of “appeasement” of India’s only Muslim-majority state. This objection to Article 370 was also congruent with the Hindu nationalists’ ideological belief that India should be a unitary and centralised nation-state.

The “reorganisation” of Jammu and Kashmir also reflects a longstanding Hindu nationalist agenda.

In 2002 the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the core organisation of the Hindu nationalist movement, demanded the state be divided into three parts: a separate Hindu-majority Jammu state; the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley; plus union territory status for Ladakh.

Simultaneously the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), an RSS affiliate, called for the state to be divided into four parts: a separate Jammu state and Ladakh as a union territory, plus the carving out of a sizeable area, also with union territory status, in the Kashmir valley to be inhabited solely by Kashmiri Pandits, the valley’s small Hindu minority who were forced to leave nearly en masse when insurgency erupted there in 1990.

Under the VHP plan, what remained of the Kashmir Valley would then be left to the Muslim majority.

The claim made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah that the autonomy enshrined by Article 370 is the cause of “separatism” in Jammu and Kashmir is disingenuous.

Largely symbolic

That autonomy had already been largely stripped away by a series of integrative measures imposed on the state by federal governments between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s.

After the mid-1960s, what remained of Article 370 was largely symbolic – a state flag, a state constitution from the 1950s that was not much more than a sheaf of paper, and a state penal code left over from the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that existed from 1846 to 1947.

Article 35A, which prevents outsiders from buying land or property in the state and assures priority in jobs to state residents, continued to apply. But again, its provisions were not unique to Jammu and Kashmir.

A number of Indian states including the north Indian states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Punjab, as well as several states in India’s north-eastern periphery, have very similar protections for native residents.

The actual cause of “separatism” in the state, which exploded in insurgency in 1990, was the de facto revocation of its autonomy in the 1950s and 1960s and the manner in which it was effected: through the collusion of puppet local governments installed by Delhi and by turning the place into a police state ruled by draconian laws.

By stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its statehood and dismembering it – an action without precedent in post-Independence India- the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government has gone far beyond that.

The edifice of the Indian Union is built on states (29, soon to become 28), moderately autonomous of Delhi. India’s union territories – there are seven, set to increase to nine from 31 October – have little to none of the status and powers enjoyed by the states.

Polarisation

A further carve-up of Jammu and Kashmir may be on the anvil, as advocated by the RSS and VHP in 2002. That could trigger polarisation between the Hindu and Muslim populations in the region.

Shia Muslims who dominate the Kargil district in western Ladakh are also unhappy with their inclusion in the new union territory of Ladakh. The reaction among the Buddhists who dominate Leh, the eastern Ladakh district, as well as among Jammu Hindus has been subdued owing to the loss of their rights given by Article 35A.

Mr Modi has promised the people of the region a glorious future of development and progress. He also stated that elections would be held soon to constitute a legislature for the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (Ladakh becomes a union territory without a legislature).

Any such election will likely be boycotted in the Kashmir valley and by most Jammu Muslims, and produce a toothless union territory government led by the BJP.

The government’s radical Jammu and Kashmir initiative diverges from the authoritarian, centralist policies pursued by many previous Indian governments in two crucial respects.

First, earlier federal governments always relied on intermediaries: clients drawn from the Kashmir valley’s political elite. Mr Modi and Mr Shah have dispensed with those intermediaries and opted for an ultra-centralist approach.

Second, Delhi’s repression in Jammu and Kashmir from the 1950s onwards was always justified by the peculiar argument that keeping Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir as part of India, by any means necessary, was essential to validating India’s claim of being a “secular state”. Mr Modi and Mr Shah, both hardline Hindu nationalists, have no use for such contorted rationales.

Radical move

In the sheer radicalism of their approach, they may have bitten off more than they can chew.

The Kashmir gambit may help the BJP’s prospects in elections in a few Indian states in October, and it may temporarily deflect attention from India’s faltering economy. But its radicalism may have re-invigorated the Kashmir conflict in a way the dynamic duo will find difficult to manage going forward.

Many democracies have regions with ingrained secessionist impulses: the United Kingdom in Scotland, Canada in Quebec, Spain in Catalonia.

What the BJP government has done is akin to what Serbia’s Milosevic regime did in 1989 by unilaterally revoking Kosovo’s autonomy and imposing a police state on Kosovo’s Albanian majority.

But the BJP government’s approach to Kashmir goes beyond what Milosevic intended for the Kosovo Albanians: subjugation.

The Hindu nationalist government seems to ultimately aspire to assimilate rebellious Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir into a form of Indian national identity defined by its movement’s ideology. This approach is akin to China’s policy towards the Uighurs of Xinjiang.

But the Hindu nationalists know that India is not an authoritarian one-party state. The outlook is grim.

Sumantra Bose is Professor of International and Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)