By: November 5, 2018

In August 2018, the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed its concern at reports the PRC had detained as many as a million members of Muslim ethnic minorities in extrajudicial re-education camps in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). At the same meeting, the PRC flatly denied the existence of “re-education camps”, with United Front Work Department official Hu Lianhe arguing that “criminals involved only in minor offenses” are assigned to “vocational education and employment training centers to acquire employment skills and legal knowledge” (China Daily, August 14). Other officials, including Xinjiang governor Shohrat Zakir, subsequently echoed his denial (Xinhua, October 16).

But the PRC government’s own budgets appear to contradict these assertions. Xinjiang’s budget figures do not reflect increased spending on vocational education in the XUAR as the region ramped up camp construction; nor do they reflect an increase in criminal cases handled by courts and prosecutors. Rather, they reflect patterns of spending consistent with the construction and operation of highly secure political re-education camps designed to imprison hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs with minimal due process.

This article supports this conclusion through examination of official PRC budgetary figures, analyzing spending breakdowns at the regional, prefectural, and county levels to produce findings of unprecedented granularity. Among its most striking conclusions:

- Spending on budget items that explain nearly all security-related facility construction rose by nearly RMB 20 billion (or 213 percent) in 2017

- Vocational spending in Xinjiang actually decreased from 2016 to 2017, as widespread camp construction began.

- Instead, camp construction has largely been funded by the same authorities that oversaw the recently-abolished system for re-education through labor.

- Spending on prisons doubled between 2016 and 2017, while spending on the formal prosecution of criminal suspects stagnated.

- Expenditures on detention centers in counties with large concentrations of ethnic minorities quadrupled, indicating that re-education is not the only form of mass detainment in the XUAR.

We begin this analysis by comparing security spending nationally with that of the XUAR.

Comparing Final Domestic Security Spending Accounts

Table 1 compares domestic security spending in the XUAR, Qinghai province and across all PRC provinces and regions (labeled “national”). Since Qinghai province has also seen violent discontent among ethnic minorities, it can serve as a kind of ‘control’, allowing us to examine security spending in the XUAR alongside a ‘normal’ province with similar issues.

While Xinjiang spent below the national average on vocational education—and just over half the amount spent per capita in Qinghai—the XUAR spent unusually high amounts per capita in 2017 on domestic security and “other domestic security expenditures”. It also spent more than three times the national average on its justice system, while spending roughly the national average on its prosecutorial and court systems [1].

The latter observation is important because the term ‘justice system’ means something very different in the PRC than in countries like the United States. In the PRC, the prosecutorial and court systems, which engage in the formal prosecution and conviction of criminal suspects, are funded separately from the ‘justice system’, which, among other functions, has significant responsibilities in re-education and general legal education. (The justice system also oversaw the former re-education through labor system; 劳动教养). For Xinjiang, this is confirmed by the fact that government construction and procurement bids related to re-education or similar “training” facilities frequently referred to them as “justice bureau transformation through education centers” (司法局教育转化中心) or simply “justice system schools” (司法学校) (Zenz, September 6). The increased funding provided to the justice system in Xinjiang is likely the result of a significant expansion of its re-education duties within the region.

Comparing Xinjiang’s figures with that of the rest of the PRC is one way to confirm the region’s enormous spending on re-education-related security expenditures. Another way is to compare the XUAR’s domestic security budgets for 2016 with those from 2017, the year the buildup truly began (China Brief, May 15).

Inflated Spending Items in Xinjiang’s Domestic Security Final Accounts

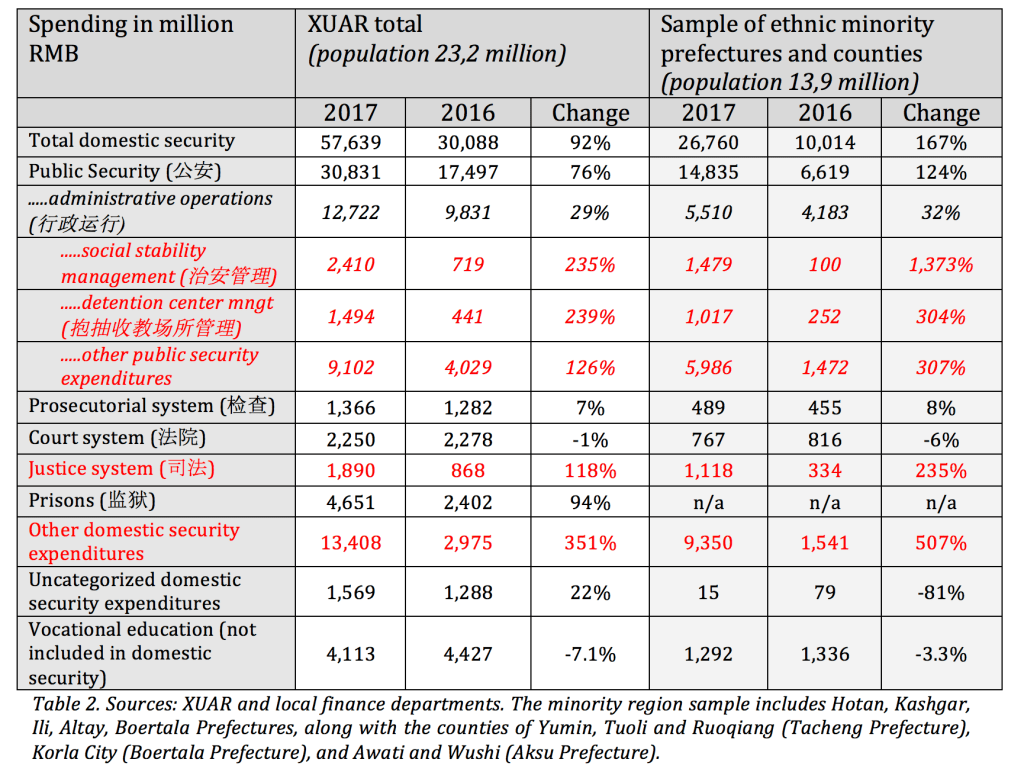

Table 2 lists total XUAR domestic security expenditures for 2016 and 2017. Listed below the headline amount are expenditures for seven domestic security sub-categories. The table also includes same figures from a sampling of ethnic minority prefectures and counties. Together, these minority territories account for 60 percent of the XUAR’s total population, and 73.1 percent of its Muslim minority population [2].

The table shows that domestic security spending in minority regions increased much more than in the XUAR as a whole (167 versus 92 percent). The increase was almost entirely due to massive hikes in five domestic security spending categories (highlighted in red in Table 2):

- Three sub-categories of public security (i.e. policing):

- Social stability management

- Detention center management

- Other public security expenditures

- Justice system expenditures

- “Other domestic security expenditures”

Table 2 also shows that spending on the prosecutorial system increased only marginally, with court expenditures actually declining in both the XUAR and in minority regions. Put differently, the XUAR doubled its spending on prisons without increasing the budget of institutions that determine prison sentences. In the meantime, spending on vocational education declined in both the XUAR and minority regions. In minority regions spending on domestic security exceeded expenditures on vocational education by nearly 20 times in 2017 (compared to only 6.5 times in 2016).

The XUAR’s spending on public security—another word for policing—nearly doubled in 2017, with this category alone exceeding the entire 2016 domestic security budget. “Administrative operations”—a public security sub-category composed mainly of police wages and benefits—typically dominates public security budgets, but in this case its contribution to increases was small. The public security sub-categories with the largest increases were social stability management, detention center management, and an obscure sub-category called “other public security expenditures”, which saw by far the largest absolute rise of all public security sub-categories. Even that rise, however, was dwarfed by the increase in “other domestic security expenditures”.

These five categories of inflated spending matter because they strongly suggest that the construction of an enormous network of ‘re-education’ camps was funded not out of the vocational training budget, but out of the portions of the XUAR budget that correspond with policing; re-education and the former reform through labor system; and domestic security. Together the five categories accounted for 98.9 percent of all security-related facility construction expenditures in a sample of 10 minority counties (discussed further below).

The View from the Bottom

More granular data local level data collected collected by the author reinforce these interpretations. A closer look at county budgets reveals consistent differences between counties with a Muslim minority population of at least 35 percent and those with a lower share. From 2016 to 2017, counties with a higher share of Muslim minority population saw a 334 percent increase in the five budget categories highlighted above, while those with a lower share saw an average increase of “only” 29 percent in 2017 [3]. In the counties with higher Muslim population shares, spending on the five categories made up 72.3 percent of all domestic security spending in 2017, while vocational education expenditures only rose by 0.4 percent.

Local governments drove the increase in domestic security spending: Domestic security spending by XUAR prefectures and counties grew by 108 percent, versus a 38 percent increase at the regional level (自治区本级) [4]. This is not surprising considering that many security infrastructure and re-education related bids—as well as most new police recruitment notices—were issued at the county level or lower. Most public bids pertaining to re-education camps identified by the author were issued by public security bureaus (i.e. the police), while a small share came from justice bureaus, which oversee re-education, as well as the former reform through labor system (Zenz, September 6).

Local level data such as these are also important for another reason: They allow us to disaggregate the sources of rapidly increased spending in the two “other” categories—“other domestic security expenditures” and “other public security expenditures”—which were, by far, the largest sources of new security spending in the XUAR. This analysis belies further the notion that budget increases went towards vocational training in any meaningful form.

Departmental Spending

County level-figures provide even more detailed breakdowns on the final spending figures for individual departments (部门决算); taken together, they show that a large portion of “other domestic security spending”, and “other public security spending” went towards construction and capital expenditures. Table 3 below lays out the results from a sample of 10 counties with full departmental breakdowns, and eight additional counties with public security department breakdowns. All of the sampled counties have a Muslim population share over 35 percent. The table shows that combined spending on basic construction and other capital investments constituted 71.4 percent of expenditures for all “other public security” and 66.8 percent for “other domestic security”.

In contrast, spending on vocational education in nine of the ten counties with full departmental breakdowns amounted to only RMB 106.8 million, of which only RMB 4.7 million (4.4 percent) was spent on construction.

Most re-education expenditures likely came from the XUAR’s domestic security budget. The region’s total budget increased by RMB 49.9 billion between between 2016 and 2017; nearly half of this increase (RMB 27.6 billion) came from greater spending on domestic security. The only other categories with increases over three billion RMB were education (where increased spending was mostly on preschooling, not vocational schooling), public services, exploration of new natural resources, housing benefits and “other spending”. However, there is some evidence that re-education construction was also funded by other budgets. For example, the county of Ruoqiang spent RMB 6 million from its “urban/rural community affairs” budget on re-education facility construction (Ruoqiang County, January 29) [5].

Conclusions

Just like the PRC’s former re-education through labor system (劳动教养), Xinjiang’s re-education campaign seems to be managed by the Ministry of Justice, administered by the public security agencies, and funded largely out of the budgets of these same authorities. Even the region’s recently amended de-extremification ordinance refers to “vocational skills training centers” (职业技能教育培训中心) as “re-education institutions” (教育转化机构), a term that both Hu Lianhe and Shohrat Zakir carefully avoided (Xinjiang PCSC, October 9). The region’s so-called “vocational training” is arguably not substantially different from the former re-education through labor system, which was abolished because the PRC government deemed it inappropriate for a modern society governed by the rule of law (Zenz, September 6).

Moreover, Xinjiang’s so-called “vocational training” campaign has not actually improved employment outcomes among the campaign’s target population. Official reports note that in 2017, 58,500 “poor persons” found employment, 17 percent more than planned, but not a large increase from the 57,800 in 2016 or the 57,900 in 2015. The same figure for the first three quarters of 2018 was 38,800, equivalent to only 51,730 per year [6]. This data provides a powerful official counternarrative to what Xinjiang’s governor is claiming. Neither the 2017 nor the 2018 XUAR employment reports refer to the purportedly successful “vocational training centers”.

These facts do not support the notion of a large campaign to improve vocational skills. Rather, the mass disappearances of Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, beginning in early 2017, almost certainly resulted in their imprisonment in de facto political re-education institutions administered by public security or justice system authorities. It is safe to assume that in 2017, billions of renminbi were spent on these highly secure facilities, where individuals undergoing “training” are involuntarily detained for indeterminate time periods. Furthermore, budget figures indicate that it is unlikely that many of the so-called “criminals involved only in minor offenses” underwent formal trials. It is therefore entirely inaccurate to label them “criminals”. Often, their only “offense” is being Muslim.

Whatever “employment training” these facilities provide is, evidently, not administered or paid for by the vocational education system. This would explain why teacher recruitment notices for the newly constructed re-education system do not require tertiary degrees or relevant skills, in stark contrast to genuine vocational education (Zenz, September 6).

The actual employment benefit of the camps’ re-education “training” is questionable. Quite the contrary: the real goal of Xinjiang’s “skills training” campaign appears to be political indoctrination and intimidation.

Adrian Zenz is a researcher and PhD supervisor at the European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal, Germany. His research focus is on China’s ethnic policy and public recruitment in Tibetan regions and Xinjiang. He is the author of “Tibetanness under Threat” and co-edited “Mapping Amdo: Dynamics of Change”.

Notes

[1] In China, the prosecutorial and court systems engage in the formal prosecution and conviction of suspects. The justice system has the more general function of providing legal education to the population, guide the work of lower-level judicial organs and engage in the political thought education of cadres.

[2] Population figures are from the 2016 Xinjiang Statistical Yearbook.

[3] The sample comprised 10 counties with Muslim minority population shares over 35 percent, and four counties with shares below 35 percent. The per capita increases were from RMB 275 RMB to RMB 1,191 for minority counties, and from RMB 272 to RMB 349 in 2017 for non-minority counties.

[4] Generally, the vast amount of domestic security spending (83.1 percent) occurred at these sub-regional levels, especially in counties.

[5] Re re-education figures were subsequently removed, but the author saved a copy of the original version.

[6] For more information, see https://web.archive.org/web/20181017191130/http://www.xjrs.gov.cn/zwgk/tzgg/201809/t8a4ac70265ad6c230165d73182e207ba.html, https://web.archive.org/web/20180120072827/http://www.shule.gov.cn/ShowNews_Content14604.shtml, https://web.archive.org/web/20181017194304/http://www.sohu.com/a/233640621_100034331