Dr. Adil Khan and Dr. Amy Macmahon

The Sundarbans and the Great Barrier Reef

While climate change threats to environment remain real and loom large , the Sundarbans in Bangladesh and the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, , two of World’s greatest heritage treasures face the danger of extinction due to use (proposed) of coal to produce energy.

Indeed, Southwest Bangladesh that faces significant environmental hazards from climate change, the result of global carbon emissions for which Bangladesh has had no part, is now confronted with a danger that is man-made. The proposed Rampal Power Plant, a coal-fired electricity station that is likely to be situated within 13 kms of the Sundarbans, world’s largest mangrove forest which is a habitat of rare species including the Royal Bengal Tigers, the proud symbol of Bangladesh’s promising cricket team, now face the danger of extinction.

Negative impacts of the Rampal Power Plant project are likely to be manifold – fly ash, discharge of hot water and waste chemicals, shipping accidents (thanks to the inefficiencies of the regulators, there have been at least 3 coal and oil spills in the last three years, and with the establishment of the Plant, frequency of shipping is likely to increase manifold, so would be the accidents). Add to this the effects of carbon emissions. Moreover, the Plant, if and when established, is unlikely to exist alone – access to power would eventually attract industries and factories that would turn Rampal into an industrial hub and consequently, an ecological disaster.

It does not require a rocket science to determine that the pursuit of energy in Rampal through coal is completely incongruous with the area’s (and also Bangladesh’s) extreme vulnerability to climate change. As a low-lying delta in a cyclone prone area, where changes in rainfall and temperature are already being felt quite acutely further damage to the ecology and the vegetation would surely endanger not only the Rampal precincts but as Late Shiekh Mujibur Rahman, the founder of Bangladesh once said in 1974 at a tree-planting speeches in Dhaka that during Pakistan time damage to the Sundarbans by the Pakistani logging contractors threatened the “very existence of Bangladesh”.

Indeed, the broader environmental issues facing Bangladesh’s Southwest region are complex and this has been further exacerbated by neighbouring India’s Farakka barrage that has reduced fresh water flows and increased salinity and distorted the local ecology. Indeed, given these existing multi-pronged vulnerabilities, Rampal Power Plant, which is being partly funded by India , is likely to make things even worse and erode further Sundarban’s fragile ecosystem, a World Heritage site of immense environmental, economic, social and cultural value.

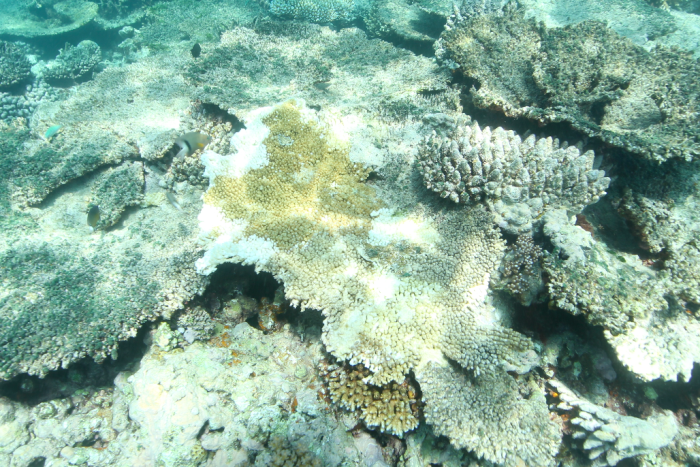

On the other side of the globe, the state of Queensland in Australia is also facing its own multi-pronged ecological challenges. The Great Barrier Reef in Queensland – the 2,300km-long ecosystem that comprises thousands of reefs and is made of over 600 types of hard and soft coral and home to countless species of colourful fish, molluscs and starfish, plus turtles, dolphins and sharks is confronted with both climate change impacts and also potential ecological risks from coal mining and shipping in the area.

Coal is already shipped through the reef and further expansion of the coal industry would simply ruin its ecological stability more. Lately, an Indian company, Adani, has been working to develop a gigantic coal mine in Carmichael, Queensland, which would clear local vegetation, drain and poison aquifers, remove agricultural land and threaten the reef via shipping and burning of coal. But the good news is this that backed by the civil society, there have been strong community resistance against the project that has resulted in changes in policy regarding dredging on the reef.

Communities in Rampal, however, have not been that lucky, they had little to no say in the development of the proposed plant and this is sad. Because should the plant become a reality (and all the indications are that it might) it is the local community that stands to suffer most. The plant would affect their farms, their air and their waterways and yet in the face of these adversities they are virtually powerless to do anything about it. True, there have been nation-wide protests, with many local groups marching in Dhaka and Rampal, with actions at times becoming violent, but government has remained unmoved. This is unfortunate.

In this context it is also important to remember that Bangladesh’s energy crisis is serious and thus it is difficult to argue against coal, a ‘cheap’ source of energy that the developed countries have enjoyed for so long. But it is also worth appreciating that while coal-based energy is cheap (many however argue that the unfavourale terms that the government has agreed to with the Indian partners on Rampal does not promise cheap cost per unit and thus, nor the price of use), its long-term effects are costly.

In this regard, it is also important to remember that as a signatory to Paris Climate Agreement that stipulates a 1.5 degree limit for global warming, Bangladesh government ought to realize that no coal technologies, not even ‘supercritical’ coal technologies – the so-called ‘clean coal’ – fit into a 1.5 degree paradigm.

Remarkably, while government’s position on coal-based energy in Rampal has remained somewhat unchanged, meanwhile, Bangladeshis have become a world leader in home solar use, implying that alternative ways of producing clean energy is possible and that a model exists already in the country itself.

Finally, both Bangladesh and Queensland in Australia also need to recognize that possessing ‘world-heritage’ sites in their territories is a gift of God and thus any action that has the potential to endanger these treasures would tantamount to tempering with assets that are of universal value and thus protecting, conserving and nurturing both Rampal and Great Barrier Reef are not only ecological necessity but also moral and spiritual obligations of the concerned governments.