Sha Marai/AFP via Getty Images

Mona Tajali, Agnes Scott College and Homa Hoodfar, Concordia University

Three Afghan women who worked at a media company were gunned down in Jalalabad in early March. In January, unidentified gunmen killed two female Supreme Court judges in Kabul.

These are the latest victims on a long list of assassinations and attempted assassinations of female politicians and women’s rights activists. Such attacks have intensified since the government began peace negotiations with the Taliban militant group in September 2020. In the past year, 17 human rights defenders have been killed in Afghanistan.

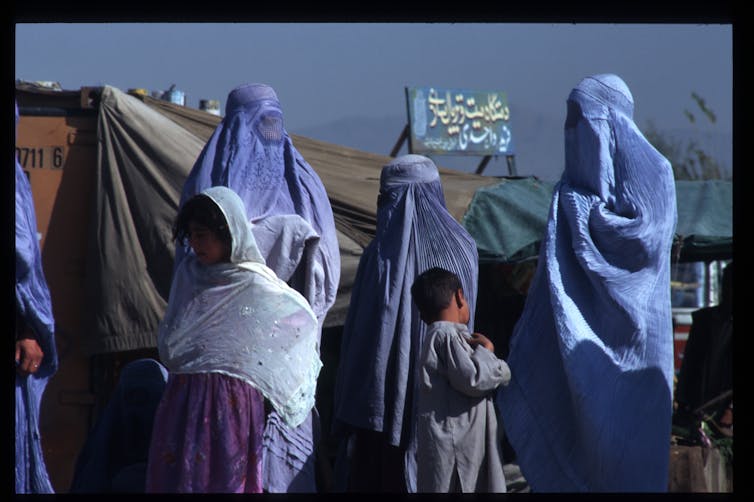

The Taliban’s rule of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 was the darkest time for Afghan women. Assuming an austere interpretation of Islamic Sharia and Pashtun tribal practices, the group limited women’s access to education, employment and health services. Women were required to be fully veiled and have male escorts in public.

We are scholars of women’s rights in Muslim majority countries, including in Afghanistan. We have been following Afghanistan’s peace talks with an eye on gender, seeking to understand how Afghan women view the prospect of their government striking a power-sharing agreement with the group that oppressed them.

Scott Peterson/Getty Images

Seat at the table

Women are a pale presence in the on-again, off-again, U.S.-brokered Afghanistan peace process underway in Doha, Qatar. The Taliban, which still controls roughly 30% of Afghanistan’s territory, has no women on its negotiating team. Only four of the Afghan government’s 21 negotiators are women – even though several women play prominent roles within the national government.

The past six months of talks have demonstrated the contradictions between each side’s stance on women’s equality and other central issues.

The government intends to preserve Afghanistan’s democratic institutions and constitution, which guarantees the rights of women and minorities as equal citizens of an Islamic republic.

The Taliban, on the other hand, is pushing for an Islamic emirate controlled by a nonelected council of religious leaders who rule based on their conservative interpretation of Islam, according to unpublished analysis by the nonprofit Women Living Under Muslim Laws, where we are board members.

Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

Roya Rahmani, the Afghan ambassador to the United States, says having women on its team gives the Afghan government more leverage to negotiate on women’s rights. That’s important because our research indicates that the Taliban maintain their extremist stance on women.

“The Taliban live in their 1990s universe and they refuse to see the reality of Afghanistan and in particular the young generations today who see themselves entitled to human rights, education, and an open public sphere,” Palwasha Hassan, an Afghan women’s rights activist, told us in an interview in December 2020.

The Taliban claims its views on women have evolved. But in some Taliban-controlled regions of Afghanistan girls are barred from getting an education after puberty – in violation of the Afghan constitution. And while women are elected and appointed to high-level posts nationally, their political participation is restricted in Taliban-controlled regions.

There is a “gap between official Taliban statements on rights and the restrictive positions adopted by Taliban officials on the ground,” according to the international nonprofit Human Rights Watch.

Roger Lemoyne/Liaison

Women and war

Armed conflicts may be primarily fought by men, who are killed or injured, but women are war victims in a different way – and therefore have different needs when it ends. Many lose their husbands and children, and thus their income, and are disproportionately displaced by violence. Rape is one weapon of war, and in some places women may be sexually assaulted en masse.

In 2000, the United Nations adopted a resolution emphasizing that women should be included in all post-conflict reconstruction efforts.

Colombia was the first country to ensure gender equity in its peace process. In its landmark 2016 accord with the FARC insurgents, which was mediated by Sweden, women were on both the insurgent and government negotiating teams, and the final accord included a chapter outlining what assistance women in conflict zones would need to start businesses, participate in politics, thrive in rural areas and the like.

Afghanistan, the first big globally brokered peace deal to follow Colombia’s, does not follow this model.

In interviews with more than 15 Afghan women’s rights leaders, we heard frustration over women’s exclusion from the peace talks given that women are the main victims of Afghanistan’s 40-year conflict.

These women support the effort at national reconciliation. But they cited the targeted killings of women over the past year as reason for concern that the Taliban’s disregard for human rights jeopardizes the longevity of any peace deal.

As one interview subject put it, “Taliban’s win is a win for ISIS, Boko Haram and other extremist groups.”

Targeting women

Outspoken critics of the Taliban’s undemocratic vision of peace have been threatened or killed.

In August 2020, Fawzia Koofi, an Afghan government negotiator and long-time Afghan parliamentarian, was shot in the arm in an attempted assassination. The attack is an instance of the gendered violence that women often face as a way to deter them from participating in politics.

Koofi refused to be silenced. Just days after her injury, she flew to Doha to attend the peace talks.

The Afghan government has made recent missteps on women’s rights, too.

In 2020, the Afghan government dissolved the State Ministry of Human Affairs, led by Dr. Sima Samar, a key advocate for women’s rights with nearly two decades of experience at the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.

Parwiz Sabawoon/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

This ministry, as the main body documenting and reporting on Afghanistan’s human rights status, could have played an instrumental role in the negotiations.

After the fall of the Taliban in the 2001 U.S. invasion, women eagerly embraced every opportunity to advance professionally in diverse sectors, from politics to social services. Today women compose around 27% of the Afghan Parliament, one of the highest rates of women’s political representation in the region.

“There is no going back,” Zarqa Yaftali, a women’s rights activist told us. “Women intend to guide their country towards peace and stability.”![]()

Mona Tajali, Assistant Professor in IR and WGSS, Agnes Scott College and Homa Hoodfar, Professor of Anthropology, Emerita, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.