Craig Jeffrey, University of Melbourne

In recent days, Australia’s foreign minister Marise Payne announced efforts to strengthen Australia’s involvement in the Indian Ocean region, and the importance of working with India in defence and other activities. Speaking at the Raisina Dialogue in Delhi – a geopolitical conference co-hosted by the Indian government – Payne said:

Our respective futures are intertwined and heavily dependent on how well we cooperate on the challenges and opportunities in the Indian Ocean in the decades ahead.

Among Payne’s announcements was A$25 million for a four-year infrastructure program in South Asia (The South Asia Regional Infrastructure Connectivity initiative, or SARIC), which will primarily focus on the transport and energy sectors.

She also pointed to increasing defence activities in the Indian Ocean, noting that in 2014, Australia and India had conducted 11 defence activities together, with the figure reaching 38 in 2018.

Read more: Government report provides important opportunity to rethink Australia’s relationship with India

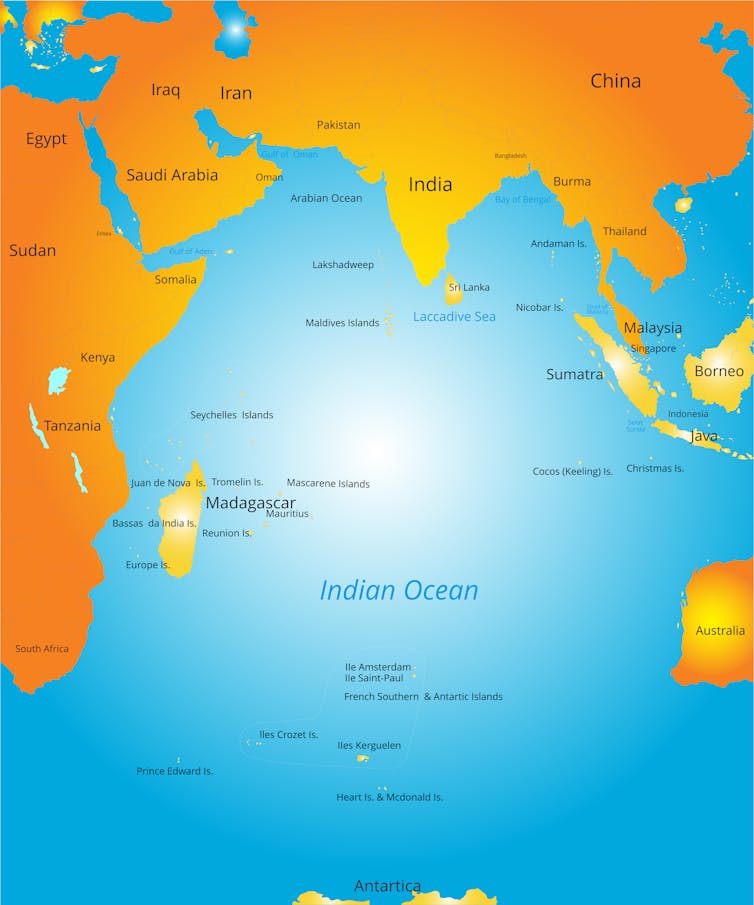

Payne’s speech highlights the emergent power of the Indian Ocean region in world affairs. The region comprises the ocean itself and the countries that border it. These include Australia, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Madagascar, Somalia, Tanzania, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

In terms of global political significance, the Atlantic Ocean can be viewed as the ocean of our grandparents and parents; the Pacific Ocean as the ocean of us and our children; and the Indian Ocean as the ocean of our children and grandchildren.

There is an obvious sense in which the region is the future. The average age of people in the region’s countries is under 30, compared to 38 in the US and 46 in Japan. The countries bordering the Indian Ocean are home to 2.5 billion people, which is one-third of the world’s population.

But there is also a strong economic and political logic to spotlighting the Indian Ocean as a key emerging region in world affairs and strategic priority for Australia.

Some 80% of the world’s maritime oil trade flows through three narrow passages of water, known as choke points, in the Indian Ocean. This includes the Strait of Hormuz – located between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman – which provides the only sea passage from the Persian Gulf to the open ocean.

The economies of many Indian Ocean countries are expanding rapidly as investors seek new opportunities. Bangladesh, India, Malaysia and Tanzania witnessed economic growth in excess of 5% in 2017 – well above the global average of 3.2%.

India is the fastest growing major economy in the world. With a population expected to become the world’s largest in the coming decades, it is also the one with the most potential.

Politically, the Indian Ocean is becoming a pivotal zone of strategic competition. China is investing hundreds of billions of dollars in infrastructure projects across the region as part of its One Belt One Road initiative.

For instance, China gave Kenya a US$3.2 billion loan to construct a 470 kilometre railway (Kenya’s biggest infrastructure project in over 50 years) linking the capital Nairobi to the Indian Ocean port city of Mombasa.

Chinese state-backed firms are also investing in infrastructure and ports in Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Bangladesh. Western powers, including Australia and the United States, have sought to counter-balance China’s growing influence across the region by launching their own infrastructure funds – such as the US$113 million US fund announced last August for digital economy, energy, and infrastructure projects.

In security terms, piracy, unregulated migration, and the continued presence of extremist groups in Somalia, Bangladesh and parts of Indonesia pose significant threats to Indian ocean countries.

Countries in the region need to collaborate to build economic strength and address geopolitical risks, and there is a logical leadership role for India, being the largest player in the region.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi told the Shangri La Dialogue in June, 2008:

The Indo-Pacific is a natural region. It is also home to a vast array of global opportunities and challenges. I am increasingly convinced with each passing day that the destinies of those of us who live in the region are linked.

More than previous Indian Prime Ministers, Modi has travelled up and down the east coast of Africa to promote cooperation and strengthen trade and investment ties, and he has articulated strong visions of India-Africa cooperative interest.

Broader groups are also emerging. In 1997, nations bordering the Bay of Bengal established the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multisectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), which works to promote trade links and is currently negotiating a free trade agreement. Australia, along with 21 other border states, is a member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) which seeks to promote sustainable economic growth, trade liberalisation and security.

But, notwithstanding India’s energy and this organisational growth, Indian Ocean cooperation is weak relative to Atlantic and Pacific initiatives.

Read more: Cooperation is key to securing maritime security in the Indian Ocean

Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper seeks to support IORA in areas such as maritime security and international law. Private organisations, such as the Minderoo Foundation, are doing impressive research – as part of the Flourishing Oceans intiative – on the migration of sea life in an effort to advance environmental sustainability and conservation.

But Australia could focus more on how to promote the Indian Ocean. In Australia’s foreign affairs circles, there used to be a sense Asia stopped at Malta. But it seems the current general understanding of the “Indo-Pacific” extends west only as far as India.

What this misses – apart from the historical relevance and contemporary economic and political significance of the Indian Ocean region generously defined – is the importance of the ocean itself.

Not just important for trade and ties

If the Ocean was a rainforest, and widely acknowledged as a repository of enormous biodiversity, imagine the uproar at its current contamination and the clamour around collaborating across all countries bordering the ocean to protect it.

The reefs, mangroves, and marine species that live in the Ocean are under imminent threat. According to some estimates, the Indian Ocean is warming three times faster than the Pacific Ocean .

Overfishing, coastal degradation, and pollution are also harming the ocean. This could have catastrophic implications for the tens of millions of fishermen dependent on the region’s marine resources and the enormous population who rely on the Indian Ocean for their protein.

Australia must continue to strengthen its ties in the region – such as with India and Indonesia – and also build new connections, particularly in Africa.

Craig Jeffrey, Director and CEO of the Australia India Institute; Professor of Development Geography, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.