BY MANOJ JOSHI

Two of the six spots renamed could be of significance, but the other four are simply points on a map. Is there a method behind this that we cannot discern at the moment?

A signboard is seen from the Indian side of the Indo-China border at Bumla, in the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Credit: Reuters

Earlier this month China’s ministry of civil affairs, responsible for social and administrative affairs under its government, published a notification changing the names of six places in Arunachal Pradesh, which China has claimed since the 1950s and now says is South Tibet. According to the state-owned daily Global Times, this is a “move to reaffirm the country’s territorial sovereignty to the disputed region.” But there is little doubt that the step is a deliberate move aimed at punishing India for permitting the Dalai Lama to visit the Tawang monastery earlier in April.

China’s renaming places is part of what is called lawfare, where countries seek to get the legal high ground to press their claims. This is not a new feature for the Sino-Indian relationship. For instance, when China wanted to press a claim to Barahoti Pass in Garhwal, it renamed it as Wu Je. Likewise, Demchok, which is in Ladakh and claimed by China, was named Parigas. Similar examples abound in cases where China or other countries dispute territory. We are familiar with the Argentinian designation of Falklands Islands as the Malvinas, or the differing names used by the Vietnamese and Chinese for the Paracel and Spratly Islands.

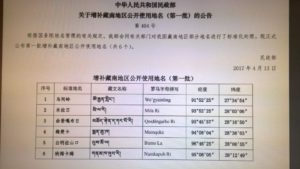

The notification on renaming of six places in Arunachal Pradesh, which China calls South Tibet.

Along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), where Indian and Chinese claims overlap, the naming and renaming is accompanied by another manifestation of the game – leaving behind tell-tale signs. Chinese patrols enter areas within the Indian claim line and leave behind newspapers, cigarette packets, old uniforms and so on. Often they paint rocks declaring it to be Chinese territory. Indian patrols do the same and whenever they come across Chinese tell-tale signs, they deface them and carry away or destroy the litter.

The Chinese ministry published its notification of April 13 giving the names in the Chinese, Tibetan and English scripts along with the latitude and longitude of the places. However, they did not indicate the original names of the places.

Plotting the Chinese given latitude and longitudes onto Google Earth results in a fascinating revelation – while two of the spots could be of significance, the other four are simply points on a map with no habitation and no prominent landmark. One would imagine that they are totally random, but perhaps, since this is just the first of many similar exercises, there is a method that we cannot discern at this stage.

Plotting “Wo’gyainling” (91° 52’ 25”E and 27°34’54”N) on Google Earth reveals a nondescript locality in Tawang 1.70 km from the monastery as the crow flies. However, some 300 metres away is the small but elegant Urgelling Gompa. Now there are scores of gompas all over the area, but the significance of Urgelling is that it is the birthplace of the 6th Dalai Lama.

“Mila Ri” (93° 52’ 25”E and 28° 03’ 06”N) – “ri” means mountain in Tibetan – is not even the highest point on a forested mountain slope. “Qoidengarbo Ri” (93° 45’ 57”E and 28°16’ 50”N) is clearly a peak, though its significance is not known to this writer. Maybe, it and Mila Ri are places of local religious significance.

“Mainquka” (94° 08’ 04”E and 28° 36’ 03”N ), or Menchuka as it is now known, seems to be just about the only place of significance renamed. It is a town with an airstrip just about 30 km from the LAC.

“Bumo La” (96° 46’ 25”E and 28°06’ 55”N) was initially assumed to the Bum La (27°43’ 31”N and 91° 53′ 32″E), the pass north of Tawang where India and China have their routine military-to-military meetings. But the coordinates provided land you up at the eastern extremity of Arunachal Pradesh, some 24 km west of Walong, while Bum La is on the western extremity. Further, Bumo La does not appear to be a pass, as the suffix “La” would suggest; it is merely a point on the slope of a mountain.

“Namkapub Ri” (95° 06’ 05”E and 28° 12’ 49”N) is the big mystery. There was an assumption that this could be the Namka Chu ( 91° 40’ 40”E and 27° 49’ 18”N), which is in the western extremity of the Sino-Indian border in Arunachal Pradesh. This was the site of the first attack by China in 1962. But the coordinates provided by the China’s civilian affairs ministry lands you on a forested slope where there are no distinct geographical features like a river, a mountain peak, pass or a dwelling of any kind.

Manoj Joshi is distinguished fellow at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

This article originally appeared in The Wire.