Donald Trump pulled the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action for Iran’s nuclear program in May 2018, insisting the agreement was not tough enough. He then reinstated sanctions and urged Iranian leaders to renegotiate another deal. But Iran is in no mood to negotiate and takes steps to annoy Trump: detaining cargo ships in the Persian Gulf, supporting Houthi rebels in Yemen who claimed responsibility for a drone attack on Saudi Aramco facilities and restarting its uranium-enrichment program. Despite sanctions, Iran continues to develop trade ties with China and other nations. Divisions within Iran prevent Hassan Rouhani, a moderate, from negotiating with Trump. Hardliners resent the United States for interference since the 1953 re-installation of the shah. Iranian leaders express doubt whether they can trust the United States. “As a result, the more Trump has clamored for a deal, the more Iranian leaders have stuck steadfastly to their preconditions of lifting sanctions, restoring the JCPOA, and even paying compensation for losses,” explain Jamsheed Choksy and Carol Choksy, scholars at Indiana University. The writers warn that Iran should not mistake Trump’s eagerness as weakness. – YaleGlobal

US President Trump is eager to negotiate a new nuclear deal with Iran, but Iran resents years of interference and sanctions

Jamsheed K. Choksy and Carol E. B. Choksy Tuesday, November 12, 2019

BLOOMINGTON: President Donald Trump has attempted to reach a new agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran since withdrawing the United States of America from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in May 2018. Tehran’s leaders have a singular opportunity to craft a new deal favorable to them due to his eagerness. They could arrange for the lifting of economic sanctions and pumping in of American and European finance, technology and industry. In Trump’s own words, a new pact would “make Iran great” without seeking “leadership change.”

France, Germany, Britain, Russia, China, Iran and even the US discussed a new framework at the UN General Assembly in late September, according to French President Emmanuel Macron. The proposed new deal would have Iran permanently abjuring nuclear weapons, conforming to a long-term framework of peaceful nuclear technology, and contributing to regional stability and noninterference in return for the US lifting sanctions. Restricting the Islamic Republic’s ballistic missiles was set aside for future discussion. Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Zarif disputed these terms, however, upon returning to Tehran.

Conditions within Iran prevent the Rouhani administration from working with the Trump administration to settle the nuclear issue.

On the military front Tehran’s Syrian ally, Bashar al-Assad, is well re-ensconced, and in Yemen, the Houthis are causing Saudi Arabia major scares – with tactical and material support from Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Iran remains self-assured that its ballistic missiles are well bunkered to withstand an American aerial onslaught. Iran’s confidence is boosted after missiles and drones evaded US-made air-defense systems during the alleged-Houthi attack on Saudi Aramco. The US Air Force’s testing, on September 28, of the mobility readiness of command and control away from its Persian Gulf base in Qatar mistakenly added to Tehran’s belief in eventually gaining strategic superiority within the region. So has Moscow’s proposal for a new Gulf security plan.

Iran’s society ranks 60/189, ahead of Turkey, Egypt and Iraq though below much-less populated and far wealthier neighbors on the Persian Gulf’s southern shores like the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, on the UNDP’s Human Development Index. The UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s World Happiness Report places Iran’s people 117/156, again above Iraq and Egypt though below the Persian Gulf states. The World Economic Forum’s Inclusive Development Index ranks Iran 27/76 among emerging nations, just after China.

For now, Iran is weathering US economic sanctions. The nation has maintained export of oil to China, and even to Syria and India, through trade and transport mechanisms that skirt US regulations. China, in particular, continues doing business with Iran in the energy, mining and transportation sectors. Even Britain circumvented US sanctions in October to make a ₤1.25 ($1.54) billion settlement with a partially state-owned Iranian bank. Iran has achieved self-sufficiency in gasoline refining. Planning ahead, Iran began cooperating with the Eurasian Economic Union. The oil ministry is laying a pipeline, with completion expected by March 2021, for carrying oil to an export terminal east of the Strait of Hormuz. Tehran and Beijing are finalizing a 25-year Chinese commitment to invest $280 million into Iran’s energy sector.

Military and social accomplishments coupled with economic endurance have emboldened officials of the Islamic Republic, including IRGC commanders, who abjure any compromise with the US. They harbor ill will for past American involvement – from the 1953 reinstallation of the shah, through chemical weapons supplies to Iraq during the 1980s war, to the ongoing sanctions.

Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, speaking after Friday prayers at Tehran in late August stressed that “negotiation under pressure is surrender,” adding “given the approach adopted by the US and Trump, they’re going to have to take this dream to their grave.” In early September, the Majlis (Parliament) National Security and Foreign Policy Committee issued a “firm warning” over President Hassan Rouhani’s remarks on readiness to negotiate with “anyone” to resolve Iran’s problems.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who maintains authority largely by playing political factions against one another, has asserted: “I had cautioned about [agreeing to] the JCPOA… repeatedly reminded the president and foreign minister.” Indeed, Khamenei has begun characterizing US sanctions as a “short-term problem” facing the country that could generate “long-term benefits” by reducing dependence on oil and gas revenues.

So, upon returning from the UN General Assembly, Rouhani had little choice but to assert at a cabinet meeting that “all the contacts revolved [only] around the issue of reviving the 5+1 group.” Zarif too held a press conference once back in Tehran to reassure opponents of reconciliation that there had been “no bilateral talks between Rouhani and Trump.” Despite those attempts to placate the anti-US faction, the president’s brother was convicted of corruption and sentenced to five years imprisonment, viewed inside Iran as a warning to the executive branch it must toe the uncompromising line.

As a result, the more Trump has clamored for a deal, the more Iranian leaders have stuck steadfastly to their preconditions of lifting sanctions, restoring the JCPOA, and even paying compensation for losses. Tehran has even countered with the possibility of “leaving the NPT [Non-Proliferation Treaty]” and enriching uranium up to 60 percent. Iran’s shopkeeper-to-customer approach to a nuclear deal may be dangerous, however. The American president’s caution should not be misunderstood as weakness. To date, Trump’s policy toward Iran has been restrained and consistent – offer rewards and impose penalties. He has punished the Islamic Republic through economic and cyber rather than military attacks – most recently by sanctioning the construction sector on October 31. But Trump is not a rejected customer who quietly leaves.

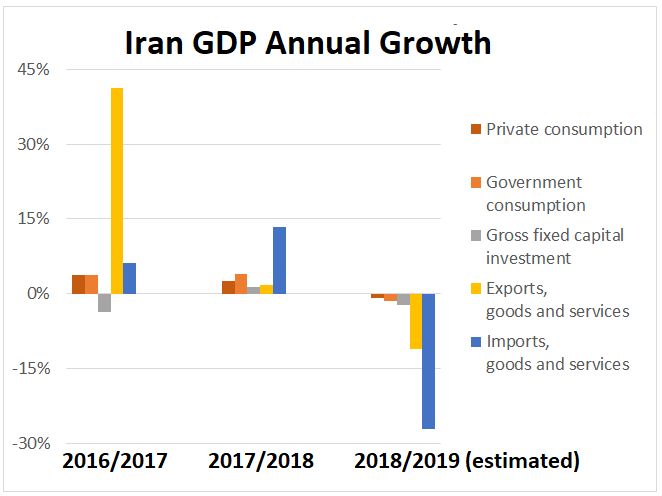

In early October, under American pressure, the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation pulled out of a $5 billion deal to develop the South Pars gas field as had France’s Total S.A. As US sanctions ramp up, the International Monetary Fund estimates Iran’s GDP will continue to fall by 9.5 percent in 2019 while inflation will rise to 35.7 percent. Unemployment will keep increasing, from 12.1 percent in 2018, according to the World Bank, due to foreign sanctions coupled with domestic mismanagement. So, the majles may authorize the Central Bank to devalue the rial. The United States has vastly more firepower ready to be deployed as well. Hence, compromising with Washington rather than repeatedly demanding the JCPOA be fulfilled is in the Islamic Republic’s self-interest.

Tehran’s aggression and deception including downing an unarmed US drone, seizing a British oil tanker, promising not to sell oil to the brutal regime of Syria but then doing so through a third party, perhaps mining commercial transport in the Persian Gulf, and facilitating strikes on Saudi energy facilities have compounded skepticism of its good faith. Despite implementation of the JCPOA in January 2016, Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization apparently retained capability to reconstitute its facilities. Tehran’s subsequent violation of commitments by increasing uranium enrichment utilizing advanced centrifuges and reactivating the Arak heavy water reactor has added to negative views. Such deeds make it difficult for the current or a future US president to reinstate the JCPOA, per Iran’s demand, although doing so is a path endorsed by the other signatories. However, a fresh agreement constraining Iran’s bad behaviors would be acceptable.

Speaking at the White House on January 2, Trump claimed, “Iran is in trouble. And you know what? I’d love to negotiate with Iran. They’re not ready… But they will be.” Yet, for now, Iran’s regime is enduring – with Rouhani insisting on October 8, “the Iranian nation’s power and status have improved after one-and-a-half-years of constant economic pressure.”

Consequently, conditions do not bode well for reinstating the JCPOA or negotiating a new nuclear deal soon.

Jamsheed K. Choksy is Distinguished Professor of Central Eurasian and Iranian Studies in the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies at Indiana University.

Carol E. B. Choksy is Senior Lecturer of Strategic Intelligence in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at Indiana University.

The article appeared in the Yaleglobal online on 11 November 2019