Felix K. Chang 9 August 2019

During the spring of 2019, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) notched up some notable successes. In March, Italy became the first major Western country to sign up as a participant. Then in April, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad announced that his country would proceed with the BRI-backed East Coast Rail Link, a railway project across peninsular Malaysia. His revelation at the BRI’s second forum in Beijing reversed his government’s earlier statements that it would cancel the project. The two successes were much needed after a year or more of unrelenting headwinds for the BRI.

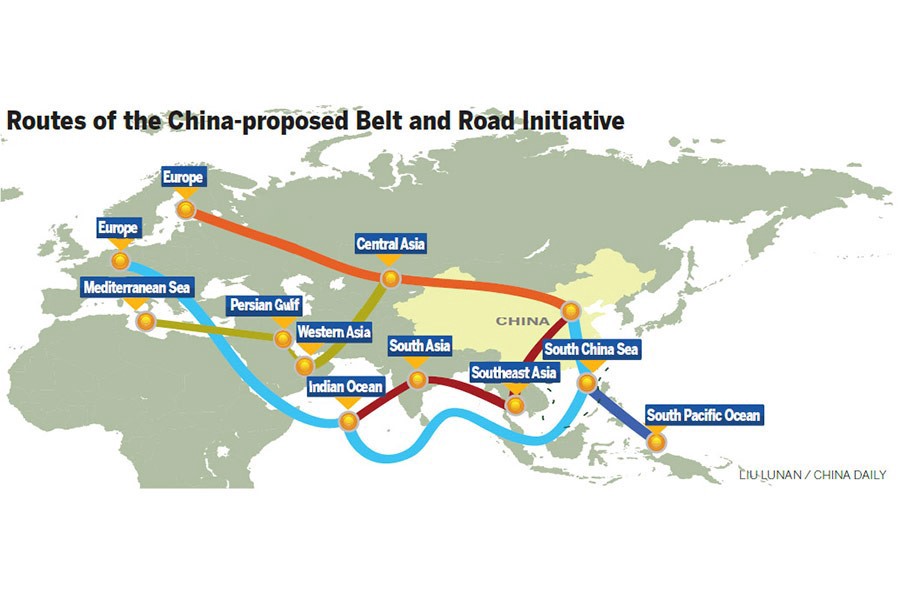

Once known separately as the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” and then together as the “One Belt, One Road” initiative before its current appellation, the BRI has never been particularly well defined. Even so, it is credited with having financed over $200 billion-worth of infrastructure projects around the world. Though often portrayed as an international development scheme, the BRI has always had a more self-serving side.[1] That was made clear by the fact that the vast majority of BRI projects required the use of Chinese companies, labor, and raw materials. The BRI also happened to be a good way for China to recycle part of its foreign exchange. Given China’s big current account surplus at the time, Chinese investments abroad eased the upward pressure on China’s currency and, in so doing, helped its export industries.

As it turned out, China’s motives behind the BRI dovetailed with those of many countries which sought foreign direct investment for new infrastructure. Using the BRI to satisfy their desires enabled China to not only keep its infrastructure-building companies busy and create new markets for Chinese exports, but also extend its political and economic influence. Some have argued that one day such influence could bring about a new “Chinese world order.”[2] If that is truly the BRI’s aim, then it is an appropriately audacious one for an initiative that Chinese President Xi Jinping once hailed as China’s “project of the century.”

Bumps in the Road

But over the last couple of years, the BRI has hit several speed bumps. Increasing international scrutiny has made the BRI seem less like a helping hand and more like “debt-trap diplomacy.” Critics have described how China often uses backroom deals (and occasionally bribes) to gain support for BRI projects; how burdensome the BRI’s financing terms have become; how the BRI has heaped massive debts onto recipient countries; and ultimately how poorly performing many BRI-backed projects have been.

Beijing has dismissed such criticism as being politically motivated. No doubt, the tensions surrounding the ongoing trade war between China and the United States have ratcheted up the hyperbole. Still, there is empirical evidence that backs up much of the criticism leveled against the BRI. Perhaps the best-documented case is the port at Hambantota on Sri Lanka’s southern coast.

Though begun before the initiative was established, the development of Hambantota’s port and, later, international airport fit a pattern seen in many BRI projects from Africa to Southeast Asia. Both were financed by Chinese loans at somewhat higher-than-normal interest rates and built by Chinese companies using Chinese labor and raw materials. Both projects were also pushed forward by a former Sri Lankan president who received money and political support from Beijing. Unfortunately for Sri Lanka, neither project paid off. Both have sat nearly idle since they were completed, leaving Sri Lanka heavily indebted to its Chinese lenders. Eventually, Sri Lanka was forced to sell almost its entire stake in the port to its lenders and give them a 99-year lease to 15,000 acres of land around it in exchange for debt forgiveness. Today, Sri Lanka’s experience has become a cautionary tale for countries seeking funds from the BRI.

Write-Downs and Write-Offs

To be sure, BRI projects have caused headaches for China, too. One of the biggest occurred in Malaysia. At first, things seemed to go well enough. Leveraging its cozy relationship with former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, China received approval for several costly, if questionably profitable, BRI infrastructure projects. But then Razak was ousted in 2018 after he was implicated in a scandal which uncovered his shady dealings with China. Razak’s successor, Mahathir Mohamad, pledged to unravel Razak’s BRI-backed schemes.

After taking office, Mahathir promptly cancelled two BRI-funded oil and natural gas pipeline projects, whose contracts had been 90 percent paid, but only 13 percent completed. But when he tried to do the same to the East Coast Rail Link, China refused to budge. After almost a year of negotiations, China and Malaysia settled on a new agreement that would shorten the railway’s length by 40 km to 648 km and lower the project’s cost to $10.7 billion, shaving off either $2.7 billion or $5.2 billion from the original price tag (depending on whether one uses the tag price cited by Razak or Mahathir, respectively, as the starting point).

Either way, China successfully put the East Coast Rail Link back on track. And that was important because many saw the railway—the initiative’s largest single project under development—as a bellwether for future BRI projects. It also helped end the seemingly unbroken stream of bad press that the initiative has received over the prior year. But China’s win came at a price. Not only did Chinse companies have to write down the value of their contracts with Malaysia, but it showed that China was willing to restructure even its biggest deals, setting a precedent for others.

Of course, China has already had to accommodate dozens of countries with troubled BRI projects by either writing off its loans or allowing them to defer payments. So far, most of China’s write-offs have been relatively small, under $100 million. But that figure might climb when the BRI’s larger loans, made after 2015, come due. Surely, China would like to avoid a repeat of what happened to its $62 billion of development loans to Venezuela. With most of the 790 projects that China financed in the country having failed and energy prices stagnant, Venezuela has been unable to repay its debts. Eager to avoid a huge write-off, China has allowed Venezuela to defer its payments and even pay in the form of oil exports. But nothing has worked. Venezuela has fallen ever further in arrears. Someday, China may have to bite the bullet and accept a steep write-down of its loans, lest Venezuela beat it to the punch and default on them.

BRI 2.0

Clearly, the BRI’s track record over its first half decade has been uneven. Even without the foreign pressure, it is little wonder that Beijing has seen the need to revamp it. If the BRI is to succeed, China needs to not only dispel notions that it engages in “predatory lending,” but also make sure that its projects earn a return. To do that, Xi announced that the BRI would start doing things differently. It would only pursue “high-quality” projects. It would also more carefully consider the level of debt its recipient countries can service. Further, the initiative would abide by international rules on bidding and procurement for its projects. Finally, in an apparent nod to past missteps, Xi promised that “Everything should be done in a transparent way, and we should have zero tolerance for corruption.”

Still, promises are not necessarily kept. And transparency is no cure-all. It cannot prevent countries from getting entangled into unprofitable schemes. Reflecting on the BRI, Mahathir cautioned borrowing countries that they “must be able to distinguish what is allowable or needed by their country and what is not.” That could be difficult, especially at a time when the global economy is slowing, and national leaders are under pressure to spur economic growth. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte agreed to participate in the BRI most likely because he thought Chinese investment could stimulate Italy’s sluggish economy. Meanwhile, China was probably attracted by the prospect of more deeply penetrating European markets through Italy’s Trieste port, which has special exceptions from customs duties. Thus, for the moment, Italy’s participation may seem like another “win-win” for the BRI, as Xi often touts. But one need only recall China’s experience with Venezuela to know how quickly that can turn into a lose-lose situation.

Sequel Success?

Will China’s revitalization of the BRI succeed? It might. Many countries still seek foreign direct investment for new infrastructure. But a better question may be whether China is still in a good position to provide that investment, at least in the quantities it did in the past. One of the factors driving Chinese interest in investment abroad—the recycling of its foreign exchange reserves—has waned in importance. While China’s reserves still total over $3 trillion, they are no longer growing. In fact, in 2019, China might run a current account deficit for the first time in decades. That means Beijing should be more interested in holding onto the foreign currency it has, rather than lending it out, if China is to hold its foreign exchange rates steady.

Moreover, China’s banking sector has come under more stress. Big Chinese banks have their hands full managing the heavy debts of China’s local governments and state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, small Chinese banks have recently become wobblier, as the government takeover of Baosheng Bank and bailout of Shengjing Bank have demonstrated. Such stresses could lower the incentive to do more international finance deals. As a result, more of the funding for the BRI may have to come from China’s national government budget. But that would mean the initiative would have to compete against other government priorities, like economic growth, defense, and social stability. The BRI could lose out in those budgetary battles.

Finally, if the BRI does become more transparent and economically responsible, as Xi described, that could actually sap the initiative’s dynamism further. With decelerating global trade and many countries already heavily burdened with existing debt, the BRI should find fewer, not more, worthwhile infrastructure investments. Depending on how closely it hews to Xi’s admonition to do things differently, BRI lending should slow. That means that the BRI’s ambitions, whatever they may be, will take longer to achieve. Oftentimes, sequels find it difficult to surpass the originals; the BRI might be no different.

[1] China Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “President Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech and Proposes to Build a Silk Road Economic Belt with Central Asian Countries,” Sep. 7, 2013, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/xjpfwzysiesgjtfhshzzfh_665686/t1076334.shtml.

[2] Bruno Maçães, Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order (London: Hurst, 2019), pp. 149-193.