A concept that will become ever more familiar – in the courts, too – with

more action needed to avoid irreversible consequences of climate change.

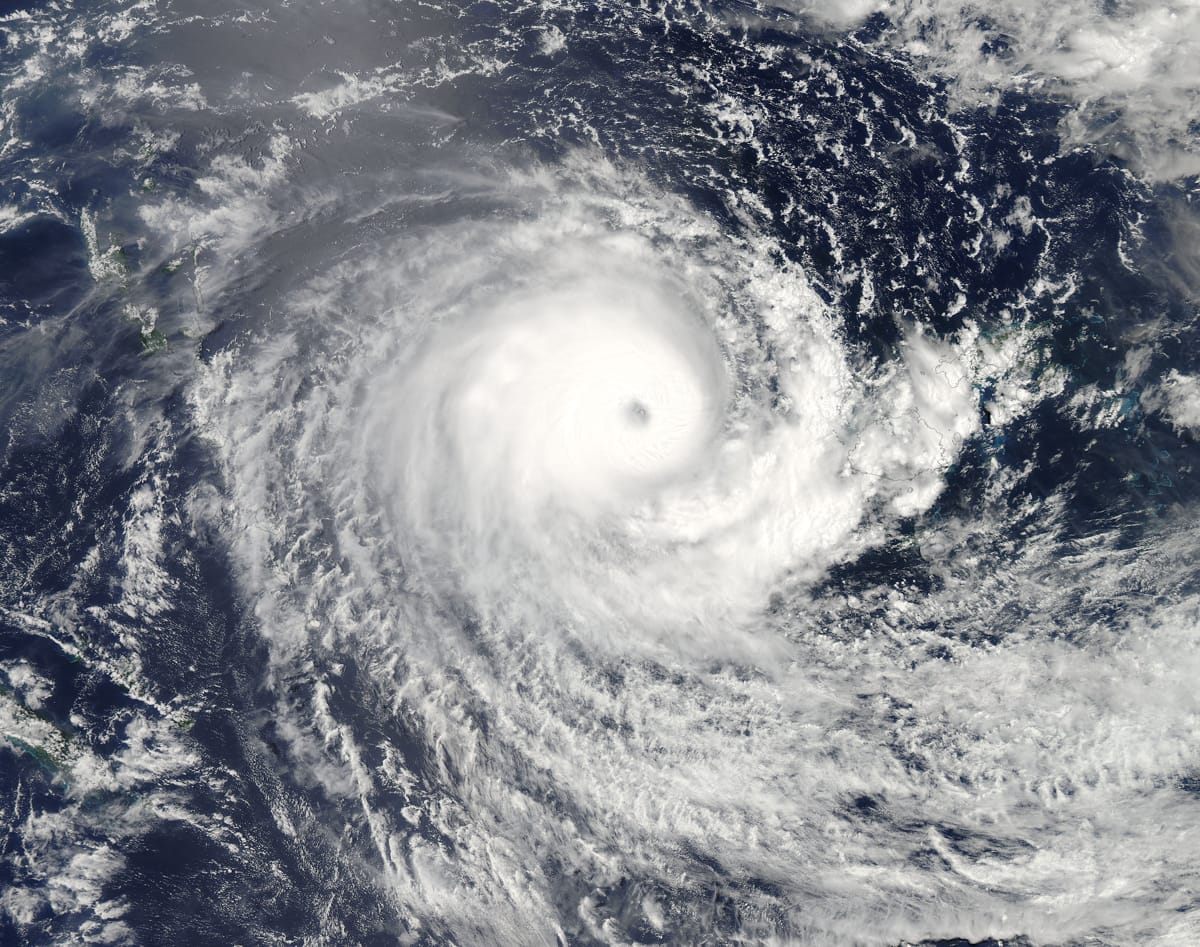

Floods in Southeast Asia, severe tropical cyclones in the Pacific, islands and coastal settlements threatened by sea level rise and millions of displaced people as a result. The effects of climate change have become so severe and unprecedented in frequency that the concept of “loss and damage” due to climate change was embedded into the United Nations Paris Agreement.

A formal financial architecture was never crafted, however, with the agreement to set up a long fought for fund achieved only last year. This marked the first of its kind, but with many problems still to be solved such as funding sources, eligibility and distribution.

It does not make it any easier that “loss and damage” is still poorly understood. There is no settled definition of what loss and damage entails, and often the distinction from climate change adaptation is fluid. Most agree though that loss and damage refers to consequences from climate change that can no longer be avoided, are unprecedented in severity, and countries are unable to adapt to. For example, Category 5 tropical cyclones in the Pacific have historically been rare, but have now occurred almost annually since 2014, causing widespread damage. Some islands were hit multiple times with little to no time to recover.

Slow onset events such as sea level rise also fall under the loss and damage umbrella. The risks have already forced the government of Fiji to relocate the villages of Vunidogoloa and Narikoso further inland due to permanent inundation and soil too salty to grow crops. Anticipating future relocations, the country has published the first set of guidelines outlining 42 villages that are identified for relocation.

The concept of loss and damage covers monetary losses to infrastructure and businesses but also recognises non-economic losses. These refer to irrecoverable loss with indeterminable value such as loss of culture, indigenous knowledge, biodiversity, life or sovereignty.

Loss and damage also raises questions of justice, given many countries in the Indo-Pacific have contributed least to climate change due to their small historical greenhouse gas emissions, yet suffer the most. It is therefore not surprising that the number of climate change-related legal cases has more than doubled since 2015, bringing the total number to more than 2,000. About a quarter of those were filed between 2020 and 2022 against fossil fuel companies and governments alike.

Litigation is increasingly used to question the commitment by governments to climate change efforts and avoiding catastrophic loss and damage. Before the climate change negotiations in 2022, lawyers from more than 20 organisations warned governments that they must deliver stronger science-based targets or risk facing further legal action.

Similarly, Vanuatu has sought an expert opinion from the International Court of Justice to clarify the rights and obligations of states under international law in relation to the adverse effects of climate change.

As a “climate laggard” with insufficient global climate policies, such developments could also have implications for Australia. In fact, there are currently 128 cases filed against Australian governments at the state and federal level, the second highest after the United States. Arguably the most prominent one in Australia has been filed by First Nations leaders Wadhuam Paul and Wadhuam Pabai from the Torres Strait Islands, challenging Australia’s failure to cut emissions, forcing their communities to relocate.

The only way for governments and businesses to avoid further loss and damage claims is deep emissions cuts, a demand reiterated by Pacific Island nations repeatedly. Progress is being made but with limited ambition. For example, Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism is meant as the major initiative to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. However, the design is questionable. New gas and coal projects can still enter the market and investments into dubious projects allow for the creation of offsets that let industry continue polluting, potentially more than before.

Such a policy is at odds with Australia joining the “Climate Club” alongside G7 countries such as Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom, but also emerging economies such as Indonesia and Argentina. Members make a commitment to ambitious climate change policies and invest into climate-friendly industrial technologies, advocate for green products and most importantly, avoid lock-in effects in fossil production processes in upcoming investments. Admittedly, how meaningful “The Club” really is, remains to be seen.

Australia can tout two more memberships: the Champions Group on Adaptation Finance with financial contributions of $10 million to define what good quality adaptation looks like, ensuring money is well spent. The second is a seat on the Transitional Committee, with the job to establish the global loss and damage finance fund.

Australia is slowly making up for a decade of policy inaction, a welcome wind of change for countries in the Indo-Pacific for whom loss and damage is a daily reality. However, inadequate policies and mere memberships to international initiatives, with minimal to no action, will not be enough to avoid irrecoverable loss and damage in the Indo-Pacific. It will continue to put a strain on diplomatic relationships in the region, with potential litigation charges against Australian governments and industry far from off the table.