By Rakesh Kumar Patel 14/7/2018

Abstract

Bollywood is largest film industry of the world. Institution of caste prevails in Bollywood similarly as in Indian society. From initiation in 1913 till date Bollywood has a rich history of producing films on various issues. Caste is a unique institution of Indian subcontinent which has now become a medium to assert the identity. Bollywood films also raise issues related to caste in its products time to time. However, few directors especially from South India have shown courage to represents insider view on low caste and their traumatic life experiences in their movies. They are telling their own stories with their own protagonists who are fighting against the system based on discrimination, atrocities and deprivation. These voices from below are not hiding their real caste identity instead asserting their rights and willingly creating their own niche in stratified Indian society. These new directors as well as their male and female protagonists do not believe in waiting for any prophet or harbinger from so-called upper castes to liberate them from their thousand years of miseries and discrimination. Here we would like to argue that twentieth century Bollywood films portrayed caste issue in idealistic form and depend on alteration in heart and mind-set to erase caste hatred and inhuman practices like untouchability. Presently, well educated, legally sound and conscious but traditionally lower caste communities are fighting to improve their social status and eliminate caste based deprivation and atrocities. Our central argument in this paper is caste has been present in Bollywood movies from inception but a new stream of authentic cinema based on ‘lived experiences’ is emerging as the perspective of insiders that is called perspective from below. This stream of cinema will make Bollywood film industry more inclusive, democratic and appropriate.

Key Words-Bollywood, Caste, identity, insider, untouchability, deprivation, atrocities, lived experiences, inclusive.

Introduction

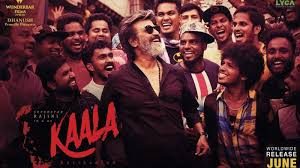

In the decade of 1990s a new wave of literature emerged as “Dalit Literature” in Marathi language and subsequently in Hindi language. This literature was based on ‘identity assertion’ (Asmitawad) and ‘lived realities and experiences’ (Bhoga Hua Yatharth). Central theme of this literary movement was negation of traditional dominant discourse created and imposed by upper castes. Mixed reactions were observed about language and style of expression of ‘Dalit literature. Presently it is an established and most discussed stream of literature. Writing autobiography has been mostly opted method because deprived maases of the country got a chance to express their traumatic life experiences through literature. Similarly, few youths from bottom of the society have entered in filmmaking and they are telling their own stories with more authentic and realistic fervor, PA. Ranjith is one of them. His films Kabali and Kaala portray life stories of evermarginalised but culturally rich masses of India. Dalit filmmakers PA. Ranjith, Nagraj Manjule and Neeraj Ghaywan are constructing a new domain and discourse in Indian cinem by telling stories of so called untouchables.

Relevant Concepts

Bollywood

It is the biggest film industry in the world, situated in Mumbai, India. Bollywood, the name of Indian film industry emerged as an imitation to Hollywood, the film industry of USA. Nicholas (1946) in his book ‘Verdict on India’ called it ‘Hindu Hollywood’. According to Dudrah (2006), “the naming and popular usage of the Mumbai film industry as Bollywood not only reveals on a literal level an obvious reworking of the appellation of the cinema of Hollywood, but, on a more significant level that Bollywood is able to serve alternative cultural and social representations away from dominant white ethnocentric audio-visual possibilities”(Dudrah2006:35).

Slums

Slums are highly populated parts of urban settlements comprised by locals and migrants from different origins who live in scarcity of sanitation, drinking water, electricity, sunlight, fresh air and proper space. Cist and Halbert define, “slum is an area of poor houses and poor people. It is an area of transition and decadence, a disorganised area, occupied by human derelicts, a catch of the entire criminal for the defective, and the down and out”.

Marginalization & Exclusion

Marginalization is a process which curtail opportunities and outcomes to those ‘living on the margins’ and at the same time enhancing the opportunities and outcomes of those who are ‘at the centre’. Marginalization combines discrimination and social exclusion which offends human dignity and it denies human rights, especially the right to live effectively as equal citizens.

Exclusion is an act to keep or leave a marginal group out from mainstream of the society, and impose prohibition on social interaction, or casts them out from it. Nadel (1969:5) defines social exclusion as “a multi-dimensional process, in which various forms of exclusion are combined: participation in decision making and political processes, access to employment and material resources, and integration into common cultural process.

Dalit

The Dalits are addressed with different nomenclatures like Chandalas, Avarnas, Namashudra, Parihas, Adi-Dravida, Ad-Dharmis, Depressed Classes, Oppressed Hindus, Harijans etc. Actually the term Dalit has been strictly used for ex-untouchables of Indian society who have occupied a unique structural location and forced social exclusion in it (Kumar 2005).

Minority

A minority is a group of people who because of their physical or cultural characteristic are singled out from others in the society in which they live, for differential or unequal treatment and who therefore regard themselves as the object of collective discrimination.

Research methodology

This paper is based on secondary sources. Concern materials collected from Books, journals, newspaper articles and Bollywood feature films for this study. We have applied textual analysis method to elaborate central theme of this paper. The textual method helps researcher to gather information about those processes by which human beings conceive the world. A text is something that we make meaning from. Textual analysis is useful for researchers working in cultural studies, media studies in mass communication. So we have used books, contents available on social media, films, journal and magazines as text and analyzed their contents. We have applied this method in the present study to understand the content of different films produced by Bollywood filmmakers which portray most important institution of Indian stratified society that is caste.

Brief History of Films with Caste Issue

First Indian motion picture ‘Satya Harishchandra’ was made in 1913. In this film a king was playing role of ‘Dom of Kashi’ at the site of funeral besides the river Ganga. First film of Bollywood depicts life of a Dalit caste and their traditionally allotted work that is burning dead bodies of Hindus. Recently film Masan raised same issue which portrayed a love story between an upper caste girl and a boy from same ‘Dom’ community who still involved in its traditional occupation of burning dead bodies beside Ganga River but this boy of 21st century is a college going student and ride motocycle.

During silent era films were mproduced on mythological characters and stories because stories were known to masses. In 1931 first speaking film ‘Alam Aara’ was produced which brought revolutionary change in this artistic field. Filmamkers started making films on diverse kind of subjects and dance songs sequences were also included in the films. After India-Pakistan division in 1947 dozens of films were made on this topic. Under the impact of communist ideology and IPTA (Indian People Theatre Association) filmmakers began producing movies on the problem of farmers and labourers and other people who were fighting for their end meets and against system. Hundreds of films were made under the impact of communist ideology during the decades of 1940s and 1950s.

Period of 1940-60 iss considered golden age of Bollywood cinema. A new stream of parallel cinema was initiated by Bengali filmmakers. Dharti ke Lal (1946), Neecha Nagar (1946), Nagrik (1952), Do Bigha Jamin (1953), began tradition of neo-realistic cinema. Satyjit Ray’s triology films ‘Pather Panchali’ (1955), Aprajito (1956), and Pratiwandi (1970), pull attention of filmmakers around the world. Kagaj ke Phool (1959), Awara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955) depicted emerging contradictions between rural and urban life, claas differences, exploitation, and other emerging individualism, selfishness, very effectively. Writers’ duo Salim-javed introduced powerful characters and stories in Bollywood which assimilated underworld, violence and crimes in Mumbai. Amitabh Bacchchan emerged as ‘youngry young man’ through his films films which reflected issues of poverty, unemployment, youth unrest, corruption, and decreasing faith in system. This style of film making remained continued till the decade of 1990 when Khan Trios Aamir, Shahrukh and Salman emerged as superstars. Films on Indian Diaspora targetting niche audiences in Diaspora communities around the world became a new and strong genre of Bollywood. Dilwae Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) got huge success with this subject.

Caste in Movies: Problem, Proud and Identity Assertition

India is country with vast diversity. We could find diversity in caste, class, race, language, and culture. Caste is paramount reality of Indin society which affects all walks of life here. K.S. Singh in his ‘People of India’ project has explained extensively about indiaan diversity. When we discuss about filmmaking in India we find that along with Bollywood films are being produced in different regions and languages. From ladakh to Tamilnadu films and music albums have strong tradition of production and entertainment. These products are concern with ethnic identity of the people residing in different locations of this country. Besides this discourse of identity it is also reality that upper castes are not ready to accept that Dalits and other lower castes should hire horse in their marriages. Inter-caste conflict and violences are much visible today. In this period of time it has become very relavant to examine the role of Bollywood in the depiction of caste based atrocities and hatred or assertion of identity by ever-deprived low castes. To understand role of Bollywood in depicting issues related to caste, we can divide them in two major catogries:

- Depiction of Caste Inequality

Caste is an important institution of Indian social system. This system of stratification is based on discrimination and exploitation. Bollywood filmmakers has made few movies which show caste as a problem and upper caste poratagonist as social reformer or agent of social change do efforts to change the caste based discrimination and hatred. Chandidas (1934), Achhut Kanya (1936,) Achhut(1940), Doosri Shadi (1947), Sujata(1959), Parakh(1960) Bobby (1973), Ankur(1974), Ganga ki Saugandh (1978), Sadgati (1981), Arpan (1983), Sautan (1983), Damul (1985), Chameli ki Shadi (1986), Rudali (1993), Tarpan (1994), Bandit Queen (1994), Mrityudand (1997), Shool (1999), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (2000), Bawander (2000), Lagaan(2001), Tere Naam (2003), Gangajal (2003), Swades (2004), Apharan (2005), Eklavya: The Royal Guard (2007), Traffic Signal (2007) Ye Mera India (2008), Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008), Delhi-6 (2009), Aakrosh (2010), Jai Bhim Comred (2011), Aarakshan (2011) Shudra: The Rising(2012), Saptapadii(2013), Samar(2013), Papilio Buddha (2013).

(2) Assertion of Caste Identity with Pride

Swades (2004), Omkara (2006), Dabang (2010) Dabang 2 (2012) Bullet Raja (2013), Fandry (2013), Two States,(2014), Peeku(2015), Tanu Weds Manu and Tanu Weds Manu Returns (2011&2015), Jolly L.L.B. and Jolly L.LB. 2 (2013& 2017), Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), Masaan (2015), Manjhi: The Mountain Man (2015), Baghi 2 (2018), Bareli ki Barfi (2017), Shadi Me Jaroor Aana (2017), Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (2017), Fandry (2013), Masan (2015), Kabali (2016), Sairat (2016), Newton (2017), Kaala (2018).

Slowly and silently but with well plan and intention number of films with north Indian upper caste titles have been increasing in last twenty years that are first two decades of 21st century. Here caste is not a problem but a matter of pride but only for tradionally dominant upper castes. Stories and lives of majority of this country are not serious concern of Bollywood Hindi filmmakers. Bitty Mishra and Chirag Dubey of ‘Bareli Ki Burfi’, Arti Shukla and Satyendra Mishra of ‘Shadi Me Jaroor Aana’, Pawan Chaturvedi of ‘Bajrangi Bhaijan’, Chulbul Pande of ‘Dabang’, Keshav Sharma and Jaya Joshi of ‘Toilet: Ek Premkatha’ are just name a few where male and female protagonists belong to a particular caste (category or Varna) i.e. Brahaman. All these films are hits and successful films. All the characters of film ‘Bullet Raja’ portrayed as Brahmans and its male protagonist corelate himself with mythological characters Parshuram to Ravana which are related to this caste. Where are the stories and problems of majorities of India? Are Bollywood filmmakers purposefully do black out the contributions of hardworking low caste majorities. Few filmmakers from low castes are now producing their own cinemas which tell the stories of life realities of deprived Dalit and other castes which is mention above in italic bold letters.

‘Kaala’: Identity Assertion by Marginals

In 2018 two important films attracted audiences as well as critiques these are Anurag Kashyap (Upper caste filmmaker from U.P. North India) ‘Mukkabaz’ and film ‘Kaala’ of PA. Ranjith(a Dalit director from South India). Deepti Nagpaul (2018) writes about the style of filmmaking of directors like Ranjith, “when filmmakers from the so-called lower castes tell their stories, they not only aim to correct the near-erasure of their history and existence from popular culture; but they also wish to tell stories from the inside, which humanise the life of Dalits and depict it in all its complexicity”. Through making these films which assert caste identity and portray life story of deprived and exploited masses are constructing a new phenomenon as well as new discourse. Tamil cinema has been amongst the most socially and politically significant industries in the state; films form an integral part of the social, cultural, and political life of the people here perhaps more than in any other region in India. Ashish Nandi (1999) insists, in his overview of Indian cinema, “Tamil cinema…has had an altogether different relationship with politics (Tamil film stars are popular not only by virtue of their cinematic appeal but also because of the close links they maintain with political parties and the checkered political career of the tamil industry itself)”. Jaylaitha, Karunanidhi, Kamal Hasan and Rajinikanth are best example of this film-politics nexus. Ranjith is also a product of Tamil cinema and he raises political issues in his films with his own style and aesthetic.With their insiders view filmmakers from below with their ‘perspective from below’ are telling their stories without any heasittaion. In a society where Dalits are beaten to death for riding horse, procession in their marriage, keeping stylish mush tache, peeling skin of dead animals, wearing good cloths and shoes, expectation of equality is far dream.

A Film of Consciousness of Majority

Director Ranjith tells the story of the life of oppressed communities through his films, Madras (2014), Kabali (2016) and Kaala (2018). He himself belongs to a Dalit caste and he uses his personal experiences and aesthetics in his fsilms. Arun Janardhanan writes about his current film ‘Kaala’, “pitted against Rajinikanth in the film is Nana Patekar, who plays a politician. Power hungry and clad in pristine white, he promises to “clean the country” of filth. Black “the colour of the proletariat” takes on feudal white in the film”.

Raj Thakrey and his organisation ‘Maharashtra Navnirman Sena’ (MNS) propagated ‘theory of son of soil’ to safeguard employment opportunites for Maharastrians. Actually, Mumbai is known as ‘City of Dreams’ and people from all corners of India came here to achieve something in life. Veteran actor Nana Patekar played role of Villain of film ‘Kaala’. In his personal life he supported ‘son of soil theory’ and opposed uncontrolled immigration of North Indians (especially migrants from U.P. and Bihar). He did same in the role of ruling party leader ‘Hari Bhai’, who opposes settlement of Tamilians in Mumbai’s slum “Dharavi”. In his earlier film ‘Krantiveer’ released in 1994, Nana Patekar played role of a migrant in Mumbai who fights against the displacement of slum dwellers by a land Mafia but in that film caste identity of characters potrayed in the film was not exposed like ‘Kaala’. Migration and inter-ethnic conflict is a serious challenge in India. Process of urbanization in India is known as ‘pseudo urbanization’as there exist huge gap between available resources, employment opportunities and mirant population. Regional imbalances in development and progress also force the people for rural to urban migration especially towards big industrial cities. City Lights (2009) movie beautifully depicts trauma of migrant family in a maximum city like Mumbai. Plot of Film ‘Kaala’ is also epic of migrants and their struggle for survival in one of the largest slum “Dhaaravi”. Veteran director Shaym Benegal made a movie ‘Dhaaravi’ (1994) portraying Om Puri as Rajkaran Yadav in lead role. In that film a migrant taxi driver lives in a one-room tenement with his wife (Shabana Azmi) in Dhaaravi. He invests all his earnings in a dubious scheme to break out from the clutches of poverty but he faces many conflicts with local politicians and goons yet continue dreaming for a better life because Mumbai is called a city of dreams.

Symbolism of ‘Kaala’

The film ‘Kaala’ is filled with symbolism to convey the message of Ambedkarism, Buddhism and communal harmony. Film ‘Kaala’ is story of binary oppositions like ‘black and white’, ‘Ram and Ravan’, ‘upper caste and untouchables’, ‘son of soils and outsiders’, ‘north and south’, ‘authority and power’ and finally good and bad. Conflict between oppositions create a new debate and discourse loudly which absent in Bollywood till date. Male protagonist of the film ‘Karikalan’ is played by Tamil superstar Rajinikanth who wears black dress and popular with nickname “Kaala”. He is patron of poor slum dwellers of Dhaaravi. In a conversation with his grand children audiences came to know the real meaning of word ‘Kaala’ in Tamil dilect is patron who saves life of the people from threats. In real life ‘Kaala’ save the interest of his fellow settlers in slum Dhaaravi. A group of young musicians and singers performs in American Jaaj style music and dance around Kaala during impotant decisions and actions which correlates Indian Dalits to American-African style of songs and dance of retaliation. Film begins with conflict between land Mafia and washermen at the location of Dhobi-Ghat (location where washermen practice their occupation). Mafia wants to break the place to construct housing society according to the will of ruling politician Hari Bhai who is self-claimed ‘patriot’ and wants to ‘clean the country’ by uprooting the low-caste, poor immigrants illegal and dirty settlement. Slum dwellers are worried to deception though they want school, hospitals, parks, playground, and community toilets. However, they could not proceed without their leader ‘Kaala’ who perceive the slum as their motherland and does not ready to leave it at any cost. Actually, he understands the game of deception offered by the nexus of greedy politician and land Mafia.

Kaala is not an elected representative but people have faith in his wisdom. In Weberian sociological perspective he possesses power and effect because settlers of Dharaavi accept him as their uncontested leader. He fights against all odds to save the interest of his people. He gave his message in very clear words, “Mere logo ka swarth hi mera adhikar hai”. During a confrontation with goons he expresses his faith in law and Indian constitution through this statement, “Kuch kaanon hum logo ke liye bhi bane hain nahi to hamko tum log kabke bahar fenk chuka hota (there are few laws in favour of poor and low caste people otherwise you people throw out us anytime)”. The director has also expresses his political views and agenda through the childhood love story of ‘Kaala’ (Dalit) and ‘Jarina’ (Muslim) who were aparted in Hindu-Muslim riots. Muslim singers present songs at his marriage anniversary celibration. Thus we read that he propagates ‘Dalit-Muslim unity theses’ in this film. We see Buddh Vihar, poster and statue of Ambedkar many times in the film which dissiminate the message that Dalit have adopted alternative religion and ideals for them beyond Hinduism.

Precious land of Dharaavi is bone of contention and plot of the films moves around the location and migrant settlements which is labelled as illegal. We come to know by dialogues and conversations that conflicting characters use many mythological symbols for instance black color is dirty color which denotes evil character of Ravna. When Hari Bhai try to insult black colour and Kaala name as dirty and hateful, he replies, “kala rang mehnat ka rang hai yamraj ka rang hai. Agar tumne hmare logo ki jamin lene ki koshish tera bhgwan karega to mai tere bhgwan ko bhi nahi chhodunga (black is a colour of hard work and colour of god of death. If your god will try to capture land of my people i will not allow him to do so). We first time see such confidence of a low caste hero against an upper castes powerful man on screen in a Bollywood film. Ruling political leader Hari Bhai conceives himself as god Rama who will kill the ‘Kaala’ and clean the dirty Dharaavi. We remember very interesting close up of a flex hording of Hari Bhai, with a quote, “I am patriot, and I will clean the country”. A boy throw a stone and torn the poster to show his anger. When Hari Bhai visit home of Kaala in Dhaaravi he do not accept water glass from a Dalit family which show caste hatred still prevails in our society. When Jarina visits Hari Bhai’s home with a positive gesture to construct housing project at Dharaavi with her NGO, he expects that a Muslim woman will touch his feet and offer worship to idol of a Hindu god. However, she rejects his expectations and dominance and leaves his home with high level of frustration and disappointment.

Kaala visits home of Hari Bhai after death of his wife and son to give him warning that he will take revenge. During conversation we find Hari Bhai puts his leg on center table and asks Kaala to touch his feet, in exchange he will forgive Kaala’s mistakes. In response Kaala, the Dalit protagonist of the film puts his legs too on same table and ask same thing to Hari Bhai. All these incidents occur in drawing room of Hari Bhai. Kaala leaves the room after heated arguement and warning of serious consequences. This history is created first time in the history of Bollywood cinema where a Dalit protagonist show his courage and guts to talk at equal level, irrespective of his position on hierarchy of caste ladder. This is new phenonmenon of Bollywood film industry.

‘Newton’ is a movie with ‘Dalit male protagonist’ who discharges his duty with full dedication and integrity even in Naxal affected region during election. We see a glimpse of Dr. Ambedkar’s portrait in Newton’s house and a discussion of Adivasi food preferences. Similarly, in film Masaan male protagonist belongs to ‘Dom’ community of Varanasi city that is designated to handle and burn corpse. He reveals his caste identity when her upper caste girlfriend wants to know about his parents and home. Celebrated Marathi director Nagraj Manjule’s characters ‘Jabya’ of Fandry and Parshya in Sairat are very much assertive about their caste identity and they are proud of it. Assertion of Dalit or caste identity in films produced by low caste filmmakers is completely new but more authentic in comparison with old Bollywood movies with caste issues. ‘Sairat’ and ‘Fandry’ also depict life stories of Dalit and traditionally low caste protagonists in lead role. ‘Manjhi: The Mountain Man’ also portrays untiring spirit of a tribal man who sacrifice his whole life for a noble cause to serve the interest of poor villagers of an isolated village. He did all this efforts in loving memory of his wife. These films which depict life realities of ever-marginalised, deprived masses which are victim of caste based discrimination for centuries have been creating a new domain in Bollywood industry. This is the cinema of the marginalised, by the marginalised but for the audiences residing at any corner of the world so that they could develop a comprehensive vision about India and Bollywood industry.

Anurag Kashyap and his ‘Mukkabaz’

In his previous films Gulal, Anurag Kashyap tried to restore ‘lost fame’ of an upper caste (Thakur) Zaminadar family. He wrote film Shool (1999) and established Yadav caste characters as villains and he rewised same here in new movie Mukkabaz (2018). Sanjay kumar a Dalit coach is attacked and paralised, while krishnakant yadav a railway officer was beaten and left in the film. Inter-caste conflict continues between Brahman and kshtriya in Mukkabaz rest are only supporting incident. This film is story of two cities Bareilly and Banaras and two castes Brahman and Kshtriya. When two coachs from Brahman and dalit castes meet in Banaras what happen watch and understand as given here: sports mafia Bhagwan Das Mishra ask a question to A Dalit caste coach “what is your name?” He tells his name, “Sanjay Kumar”. To know his caste he again ask “Sanjay Kumar what Brahman, Kshtriya, Kayasth?” Sanjay Kumar says “Harijan” which you don’t like to say. Consequently, Bhagwan Das returned the glass of water and order for another one separately. This scene and attitude reveals how an upper caste man hate and discriminate a Dalit caste even an equally qualified man. In this film male protagonist a struggling brawler Sharavan Kumar Singh belongs to Thakur upper caste terrorise his Yadav caste boss Krishna Kant a railway officer and he urinates in his pants with fear. Anurag in this film insulted low caste (Yadav) and Scheduled caste coach. It seems he is quite sure that in Indian society which is based on caste stratification only upper two Varna will sustain and others will loose and live udignified life. Bhagwan Das Mishra, Sunaina Mishra, and Shravan Kumar Singh at the climax of film do an agreement for peaceful coexistence. Sharavan sacrificed his carrier for his love and receive blessing from Bhagwan Das Mishra as reward. Thus anurag establish Vrana syatem through his film a long time awaited project and dream. This might be hyper-realism or projection of subconscious mind or frustration of Anurag. Undoubtedly, Anurag has different and unique style of filmmaking which is inclined to portrayal of reality prevails in the society. In his recently released film ‘Mukkabaz’ characters are very vocal about their caste identity.

At the climax it seems filmmaker has already determined to establish ‘Varna System’ through his project. We could speculate that it might be depiction of hrash realities existing presently in the country or it is mere projection of upper caste subconscious of Anurag Kashyap. Is constitutional provision like social justice and affirmative action are in danger and deprived masses are so helpless that they would not react against their exploitation and atrocities? Answer of this question is sui-generic movement on 2 April 2018 against efforts of weakening SC/ST atrocities and protection act. People have become so aware about their right that they could call and organise a mass movement through social media without involving any political leader/party or pressure group. Here we would like to mention views of Dipankar Gupta (2005) who believes that caste based discrimination and hatred withered away, he explains, “with the breakdown of the closed village economy and the rise of democratic politics, the competitive element embedded in caste has come to the fore.This has resulted in the collapse of the caste system but also in the rise of caste identities…caste identity, and not the system, underpins and informs, caste politics. This point of view is gradually gaining ground among anthropologists who are now explicitly beginning to acknowledge the descrete nature of caste identities and the consequent clash of multiple hierarchies”. However we do not accept his thesis that caste as a system and village as a community withered away. Both institutions exist very much in our Indian society. People are asserting their caste identity and expect that low castes will perform their duty according to the will of their upper caste masters, consequently many kinds of conflicts emerge which we could see in our films also.

Casteist Cinema from 1990 to 2018

Decade of 1990s bring paradigm shift in Bollywood cinema. LPG schemes were introduced in Indian economy. Professionals and capital flows increased at large measure across the nations consequently Indian Diaspora reached to the centre stage of the Bollywood films. Punjabi and Gujrati Diaspora live in maximum numbers in USA, UK, Canada and Australia and other developed countires. Bollywood focused and targeted those niche audiences and a new trend of Diaspora films began depicting stories of Punjabi, Rajstahani and Gujarti families in India and abroad to connect them and earned maximum money. Diaspora films of Bollywood depict stories of elite and upper caste Diaspora who migrated with higher education and skill to developed countries like UK, USA and Canada. We could not any Bollywoood film which tells stories of Fiji, Mauritious, Sri Lanka and Carrebian countries as indentured labourers a kind of slave.

Bollywood filmmakers have started capturing scenic views of small towns settled at different corner of the country with fresh stories and approach. However, characters and plots of these films are telling stories of few upper castes with feeling of pride and targeted assertion. Observe the titles of characters in films produced after the year of 1995, we could easily understand paradigm shift of production in Bollywood. Here are few celebrated titles Mehra, Malhotra, Singhania, Chopra, Sharma, Singh, Kapoor, Shukla, Dube etc. If something positive is happening in the society the harbinger has an upper caste background in a Bollywood film. In such circumstances a relevant question arises in the mind what is the contribution of other communities and masses of the country? Either they are mere consumer/audiences or their contribution is blacked out through a conspiracy by elite Bollywood. Is Bollywood concern about their problems, miseries or achievements? I think emergence of a new cinema with a “perspective from below” with an insider’s view is counter to elitist and biased approach of traditionl Bollywood. These films produced by Dalit and backward category directors will construct their own niche domen and audiences like Dalit literature did in 1990s.

| Conclusion

Films are one form of literature and mirror of society too. Cinema reflects those realities which are happening in the society. Caste is an Indian institution and it affects each walks of our life here in India and cinema is not any exception. When we evaluate contents and composition of people involve in production of films we find dominance of traditionally upper castes. Very few films and filmmakers raised the issues concern with Dalits and other marginalised sections of our society though they comprise largest section of Indian society. Not only their number but issues related to their lives also are vast and diversified. This majority are largest audience of Bollywood films too but they and their problems are blacked out from cinema industry. Though Bollywood is called great melting pot and dream world for everyone but in reality it supports casteism, nepotism, racism and regionalism. Recent dispute between Karan Jauhar and Kangana Ranawat revelas that Bollywood possess attribute of nepotism and promote it. She identified Karan Jauhar as “movie mafia and supporter of nepotism”. Bollywood is largest film industry in the world and it has a rich history of past hundred years. When we search we find that mythology, caste-class and communal contents were portrayed in Indian cinema during pre independence era. However these films never had a successful hero with Dalit, Muslim, Sikh or Christian background justifying the caste and community hierarchy of the Indian society in the times as well. Deshpande has pointed out very eloquently “in most films the protagonist could be poor but generally not Dalits, Christian, Sikh or Muslim surnames and the hierarchy of characters clearly established this” (Deshpande2007:97). In Hindi cinema we find a single film Chachi 420, use ‘Paswan’ title for his male protagonist. Stories and characters always present there but as protagonist with their caste title they were never portrayed. Bollywood ignores poor, Dalits, minorities and rural India. Tamil filmmaker PA. Ranjith says on the release of his film ‘Kaala’, “in my films symbolism is secondary; it’s the assertion that forms a crucial parts. There have been films in the past that depict Dalit characters and lives. They were made by non-Dalits, who view us through a lens of pity. Our world is shown as colourless and poverty-stricken. Yes, we are economically poor but not culturally so. Where is the depiction of our vibrant culture, music and food? Why is our world shown bereft of it all?” if we do study of Bollywood films we will find that most of the film depict Dalits in minor roles of poverty and helplessness. They need help and support with sympathy from any upper caste harbinger to liberate them from tight corner situation. Aamir Khan’s successful movie Lagaan (2001) show this kind of inclusive agenda. Name of Dalit character in this film is ‘Kachra’. Aamir Khan (Bhuvan) embraces ‘Kachra’ and includes him in his cricket team as spinner while whole village oppose to include an untouchable in the team. This kind of ‘token inclusion’ we could observe in many Bollywood films for instance ‘Achhut Kanya’ and ‘Sujata’. Marathi filmmaker Nagraj Manjule whose films Fandry (2013), and Sairat (2016) broke new ground in the depiction of caste relations explains, “i understand that films such as Jabbar Patel’s Mukta (1994 about and upper-caste woman who falls in love with a Dalit activist) are well-intentioned. But why do these films have to adopt a patronising tone? Producers, directors, lyricists, writers, hero and heroines of Muslim community comprise sizeable part of Bollywood film industry but when we observe minutely we find that most of them belong to upper caste-class Muslims (Ashraf, Ajlaf and Shias). Khan trio are best example of this dominance and they are continuing from one to another generation. If we evaluate present composition of Bollywood stakeholders a large chunk is comprised by urban and upper caste, class. In the beginning respected families don’t like to send their members especially females to Bollywood film industry but modelling as well as films is filled with girls with upper caste-class background. Reason is simple that is involvement of huge amount of money in this business of entertainment. We know only two Dalit lyricists Shailendra and Dr. Sagar in Bollywood. Others are either unknown or not capable to enter here. Common man who is majority of this nation is treated outsiders or meaningless by bollywood filmmakers. Dalit directors PA. Ranjith, Nagraj Manjule, Neeraj Ghaywan are constructing a new domain and discourse by telling stories of so called untouchables which had been neglected in both real and reel life till date. This new stream of cinema will certainly complete the picture of incomplete, biased and unjust Bollywood industry.

References Damodaran, K. & Gorringe, Hugo (2017) Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema, in South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, The University of Edinburgh. Deshpande, Anirudh (2007), Indian Cinema and the Bourgeois Nation State, EPW 95- 103. D’souza, Dipti Nagpaul (2018) Caste in New Mould, in Indian Express, on 10 June Sunday. Dudrah, Rajinder K. (2006) Bollywood: Sociology Goes to the Movies, Sage Publication: New Delhi. Giddens, A. (1993) Sociology, Blackwell Publishers, London. Gupta, Dipankar (2005) Caste and Politics: Identity over System, in The Annual Review of Anthropology. Nandy, Ashish (1999) The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability and Indian Popular Cinema, Zed Books, London. Scott, John & Marshall Gordon (2009) Oxford Dictionary of Sociology, OUP, USA.

|