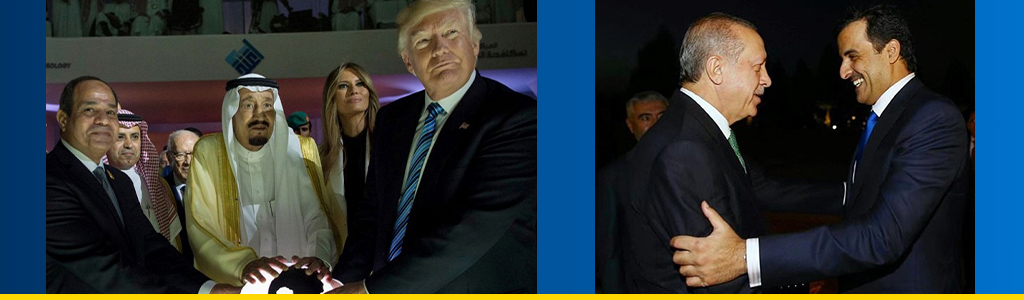

Two Opposing Middle East Alliances for the US | YaleGlobal Online Saudi Arabia and Iran are leading rivals in the Middle East. Religious differences help fuel the rivalry, as Saudi Arabia is primarily Sunni and Iran is Shia, yet oil interests, trade and fears about how democracy could dislodge absolute power matter, too. Alliances in the Middle East are delicate affairs. Saudi Arabia, pushing hard against Qatar in 2017 in its efforts to end support for the Muslim Brotherhood, only pushed the small nation closer to Iran and Turkey. Author Dilip Hiro has long studied the history of alliances throughout the Middle East, and he analyzes how worries about the Muslim Brotherhood divide the region. In 1928, teacher Hassan al-Bannā founded the Brotherhood, which eventually became the world’s most influential Islamic organization with a range of reformist goals, including charitable distribution, education as well as cultural, economic and political empowerment of communities. Hiro details how the divide over the Muslim Brotherhood forces the Trump administration to recalibrate its own relationships in the Middle East, with democratic values and human rights often the casualties. – YaleGlobal

The Middle East is divided over the Muslim Brotherhood and two alliances emerge: Iran, Qatar, Turkey versus Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE

by Dilip Hiro Tuesday, July 9, 2019 Yale Global Online

LONDON: An alliance of Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates faces increasing opposition from tightening links between Turkey and Qatar that are welcomed by Iran. Ironically, the latter group received a boost two years ago when Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, working with Egypt, the UAE and Bahrain, led an economic and diplomatic blockade of Qatar to compel the tiny neighbor to meet 13 demands that included severing trade and diplomatic ties with Iran and closing a Turkish military base established in 2015. The anti-Qatar axis alleged that Qatar was aiding terrorism by funding such Islamist groups as the Muslim Brotherhood.

By so doing, bin Salman grievously undermined his kingdom’s established strategy of rallying the region’s Sunni countries against Shia Iran. Counterproductively, he pushed Qatar into the welcoming arms of Iran and Turkey. Qatar and Turkey are predominantly Sunni as are Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt.

Hostility towards the Brotherhood is the defining signature of the Riyadh-Cairo-Abu Dhabi alliance. Hassan al Bannā, founder of the Brotherhood in Egypt in 1928, described it as an all-encompassing entity with a reformist Islamic message, a political organization, a scientific and cultural union, an economic enterprise and a social idea. Over the subsequent decades, the Brotherhood spawned dozens of Islamist groups in many Muslim countries who support political Islam and independently run Islamic charities. These charities raise funds among well-off Muslims, including migrants settled abroad, to run hospitals and schools, and pay monthly stipends to poor widows.

In Egypt, the Brotherhood renounced political violence and, while officially banned, participated in parliamentary elections in alliance with secular parties from the mid-1990s. In 2005, when allowed to contest a third of 444 legislative seats, the Brotherhood scored 60 percent success. President Hosni Mubarak responded with heavy-handed repression. Therefore, in the early stages of the Arab Spring revolution, the Brotherhood stayed away, depriving authorities of a rationale for brutal suppression of the new movement. After the overthrow of dictatorial Mubarak in February 2011, it functioned openly. In Egypt’s first free and fair presidential poll in June 2012, Brotherhood leader Muhammad Morsi emerged as the victor. A year later he was overthrown by generals led by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi who soon banned the Brotherhood and seized its assets. Under el-Sisi’s watch, security forces fired on peaceful Brotherhood supporters on five occasions, killing 1,150 people. The number of political prisoners soared to about 60,000.

Sisi’s regime received generous financial aid from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Their absolute monarchs, who base their legitimacy on implementing Islamic precepts, fear the Brotherhood because its leaders have proved that a Sharia-based government can be established through the ballot box. That is the primary reason why Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party – or Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP, led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – feels an affinity with the Brotherhood. Under Erdoğan, this political entity rooted in Islamism won power democratically in 2002 in a country with a secular constitution.

By the same token, the Brotherhood has cordial relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran, which regularly holds elections with moderates and hardliners vying for power. Though Brotherhood ranks and leaders are Sunni, they consider Shias as equals.

During the 2011 Arab Spring, Qatar’s Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani foresaw the Brotherhood achieving power through the ballot box throughout the Arab world. Therefore, he and the Doha-based Al Jazeera TV channel backed the Brotherhood. When the counterrevolution took hold, many Brotherhood leaders found refuge in Doha while others moved to Istanbul.

In June 2013 the Qatari ruler abdicated in favor of his son Tamim. With that, an earlier plan to hold elections for two-thirds of the 45-strong Consultative Assembly, hitherto fully nominated, was shelved. Under the 2004 constitution, the government can ratify new laws only after debate by the Assembly. The ruler repeatedly postponed promised elections, with the next date likely to be June 2022, five months before Qatar hosts the FIFA World Cup tournament, an event of practical interest to Turkey.

Four months before the Saudi-led economic and diplomatic assault on Qatar, Turkey’s Tekfen Construction Company signed a joint venture with Qatar’s Al Jaber Engineering Company to build a 40,000-seat stadium in Doha to host World Cup matches. It was in the mutual interest of Ankara and Doha to ensure uninterrupted supply of building materials for this project. Turkey rushed cargo ships and planes loaded with food to Qatar. So did Iran and trade ballooned. Iran’s airspace came to host 200 more Qatar Airways flights daily than pre-blockade.

In November 2017, Turkey, Iran and Qatar signed an agreement, with Iran named as transit country for Turkish-Qatari commerce. The next month, Ankara bolstered troops to 3,000 at its base in southern Doha, and its tanks paraded along the capital’s roads. In August 2018, US President Donald Trump triggered a currency crisis in Turkey by doubling tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminum to pressure Erdoğan to release Christian pastor Andrew Brunson, held on terrorism charges for two years. Qatar’s emir flew to Ankara and announced injection of $15 billion into Turkey’s financial system. That stabilized the Turkish lira. “We stand by the brothers in Turkey that have stood with the issues of the Muslim world and with Qatar,” Tamim declared.

His mention of “issues of the Muslim world” was an oblique reference to Erdoğan’s rotating chairmanship of the 57-member Organization of Islamic Cooperation. In that role, Erdoğan had called an emergency summit in Istanbul a week after Trump’s December 2017 decision to move the US embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in violation of 10 UN Security Council resolutions. The summit declared East Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine. Emir Tamim was one of the 50 heads of state or government who attended. But Saudi King Salman bin Abdul Aziz, bearing the official title Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques – referring to ones in Mecca and Medina – failed to do so despite the fact that Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem is the third holiest shrine in Islam.

Relations between Ankara and Riyadh cooled further in the aftermath of the gory murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018, widely believed to have been masterminded by Prince Bin Salman’s office. Unsurprisingly, when it came to passing on the rotating Organization of Islamic Cooperation chairmanship to Saudi Arabia the following May, Erdoğan stayed away. Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu did the hand-over at the low-key foreign ministers’ meeting on the eve of the summit in Riyadh.

By then, regional tensions had risen sharply. Damage to four oil tankers near the UAE port of Fujairah on 12 May followed Trump’s secondary sanctions on Iran’s oil exports. As the Gulf Cooperation Council chairman, King Salman called an emergency summit to which he invited his Qatari counterpart. Tamim sent Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdul Rahman Al Thani instead. On return to Doha, he disassociated himself from the summit’s communique: “They adopted Washington policy towards Iran, rather than a policy that puts neighborhood with Iran into consideration.”

Much to the frustration of the Saudi crown prince, Qatar has strengthened already strong links with the United States. In mid-January, its government agreed with visiting US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to expand the Al Udeid Airbase, which hosts 11,000 American troops and functions as the forward headquarters for the Pentagon’s Central Command. A month later, to the annoyance of the Trump administration, Tamim sent a congratulatory cable to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in honor of the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

While Trump remains allied to the Riyadh-Cairo-Abu Dhabi Axis, he cannot sideline either Qatar or Turkey, the only Muslim member of NATO with the second largest military after the United States. Both countries continue to maintain close relations with Iran, his bête noire.

Dilip Hiro’s latest and 37th book is Cold War in the Islamic World: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Struggle for Supremacy, published by Oxford University Press, New York; Hurst & Co., London; and HarperCollins India, Noida). Read an excerpt. Read a review. Listen to a podcast interview with Hiro.