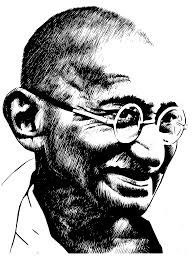

Gandhi, also called the Father of the Nation was the first casualty of Hindu nationalism in India. Today he is the subject of mockery and disdain for a country reveling in right wing nationalism.

Earlier this year, on the 154th birthday of Mohandas Gandhi, a national

holiday in India, three of the top ten Twitter trends in the country celebrated

Nathuram Godse, the Hindu fundamentalist who assassinated Gandhi.

The month before, at one of the biggest Hindu festivals in India, the Ganeshotsava,

posters of Godse were displayed along with those of Hindu deities in the state

neighboring Gandhi’s birthplace of Gujarat. This would be akin to carrying posters of

John Wilkes Booth at a President’s Day parade.

Seventy-five years after his assassination, Gandhi, the man who led India out of

British rule, revered in the west as the exemplar of nonviolent protest — has become

a casualty of India’s lurch toward Hindu nationalism. The Mahatma is now reviled by

Hindu nationalists for failing to establish a Hindu government in India when he had

the chance. Instead, Gandhi advocated Hindu-Muslim unity in one secular state,

India, the world’s largest Democracy.

On Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube, Godse, the assassin, has a newfound

fanbase that portrays him as a hero. Executed by hanging in 1949, he had tried to kill

Gandhi twice before he succeeded: once with a knife, once with a dagger. In both

cases, Gandhi declined to press charges, so the young man was released despite

openly threatening the leader. The third time he used a gun. He blamed

[outlookindia.com]Gandhi for the loss of Pakistan during partition (although Gandhi

opposed partition), felt Gandhi was pro-Muslim and feared that Hindus would

continue to lose ground if Gandhi remained as an influence on the government.

Godse was a member of the Hindu nationalist paramilitary organization Rashtriya

Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which is the ideological fountainhead of Prime Minister

Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). And since Modi was first elected in

2014, the narrative blaming Gandhi has taken hold.

On Colaba, a bustling, touristy street in Mumbai, a seller of memorabilia across from

the Taj Mahal Palace hotel was not impressed when I picked a bronze souvenir

depicting Gandhi on the 1930 Dandi March, protesting Britain’s tax on salt. He said

the only people who buy things like that are “white foreigners.”

The merchant, who hails from Gujarat, did not wish to be named but told me that a

new generation of Indians has a different opinion of the man referred to as “the

father of the nation.” . He tells me that Gandhi partitioned India to appease

Muslims and appear as a humanist to the world to be labelled a

‘Mahatma’. “The world loves to put pseudo secularists like him on a

pedestal but we are now aware of his reality”

This school of thought is not an aberration. Modi has referenced Guruji Golwalkar,

who led the RSS at the time of the assassination, as a major inspiration

[caravanmagazine.in]. It was Golwalkar who had stated [thewire.in] at a rally of the

Hindu right wing on December 7 1947 that “Mahatma Gandhi wanted to keep the

Muslims in India so that the Congress [party] may profit by their votes at the time of

election . . . We have the means whereby such men can be immediately silenced, but

it is our tradition not to be inimical to Hindus. If we are compelled, we will have to

resort to that course too.” A month later, Gandhi was killed.

At the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat, one of the homes of the Mahatma, I

encountered teenagers posing for selfies and picnicking on the lawn. When I asked

questions about Gandhi, they seemed uninterested, one says, he is the man

whose face is on the Indian rupee.

Another college student mocks Gandhi, writing him off as merely the grandfather of

‘pappu’ (a derogatory term coined for Indian opposition leader Rahul Gandhi, who is

not in fact related to the Mahatma).

Gandhi has never been this unpopular. The 1982 Richard Attenborough biopic about

him won eight Academy Awards and introduced a new generation to the Indian

independence fighter.

As recently as 2006, a Bollywood blockbuster “Lage Raho Munnabhai” (Carry on

Munnabhai) saw Gandhi become cool again on the streets of India. The film

depicts a small-time con man who in an attempt to win over his lost lover goes

through a transformation as he accidentally runs into the works and writings of

Gandhi. Through Gandhi’s ideas of non-violence, social justice, and secularism, the

protagonist is able to fight societal evils and in the process win back his idealistic

lover.

A catchy blockbuster song [youtube.com], “Bande Mein Tha Dum Vande

Mataram" (The man (Gandhi ) had courage, I salute thee my nation)

reminisces about the life of Gandhi and invokes him to return from the dead to

save the country.

However, since ultra-nationalist Hinduism took hold, Gandhi’s image has

floundered. In 2019, a prominent member of parliament from Modi’s BJP, Pragya

Thakur, called Godse, Gandhi’s assassin, a “patriot [hindustantimes.com]” on the

floor of the house. Only after a national outcry did Modi condemn

[timesofindia.indiatimes.com] her words, calling them “unacceptable in a civilized

society.”

Still, the Hindu Mahasabha, another extension of the RSS, now celebrates Gandhi’s

murder in public as “Shaurya Divas” (Bravery Day) and on the 71st anniversary of

Gandhi’s assassination, in 2019, recreated his murder [ndtv.com] for the cameras to

loud applause from followers. In June of this year, Modi’s Union Minister, Giriraj

Singh, called Gandhi’s assassin “a good son of India [thehindu.com]” while speaking

to reporters during a tour. The Congress party’s general secretary, K. C. Venugopal

said, “The PM’s silence tells you he approves of their every word

[economictimes.indiatimes.com].”

Over the last several years, history textbooks in India have been revised to excise

facts that don’t support the favored narrative. “The background of Gandhi’s assassin

Nathuram Godse and the fact that Gandhi stood for Hindu-Muslim unity and

opposed Hindu majoritarianism after Independence have all been removed,” the

Indian Express revealed [outlookindia.com] earlier this year.

A glance through social media platforms will reveal young YouTubers and tik-tokkers

presenting the “debauched” videos of Gandhi, many referring to him as the ultimate

predator of women. (Gandhi took a vow of celibacy for religious reasons after having

four children with his wife.) A video presenting the “Dark Side of Gandhi

[youtube.com]” — intimating that he was both a racist and misogynist — has gained

traction. On WhatsApp and Facebook, the man who led India to independence is the

butt of jokes, while Modi is hailed as the leader who has won "real independence” for

the nation through the projection of its Hindu glory.

Atul Dodiya, one of India’s leading artists, is trying to keep the Mahatma alive

through his paintings and retrospectives. An artist deeply influenced by Gandhi, he

says his 1997 work on him titled “Lamentation” was a result of the despair he felt

after one of the worst communal riots in the history of India, the 1993 Mumbai riots

that followed the demolition of the iconic Babri Masjid by leaders of the BJP and the

RSS. He says it was the ultimate assault on Gandhian ideas. Seventeen years, and

more than 200 paintings for various galleries later, he is trying to preserve the hope

that India will not turn its back on the man who sacrificed his life for the freedom of

the nation.

But in today’s India, Modi invokes Gandhi only when he needs him.

In June, at United Nations headquarters in New York, Modi offered a floral tribute

and bowed before a bust of Gandhi. In September, as world leaders arrived in India

to participate in the G20 summit, Modi led President Joe Biden, British Prime

Minister Rishi Sunak, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres and other leaders to

the Gandhi memorial at Rajghat, where the Mahatma’s ashes are buried.

Ceremoniously, one by one, he placed a scarf around their necks, made of the

homespun fabric promoted by Gandhi during India’s independence movement

against the British.

Gandhi’s words, “My life is my message,” is written on the wall there.

But on the subject of Gandhi, Modi’s message is decidedly mixed.

(This article was first published in the Washington Post )ra