Ayodhya, India, 2022RAGHU RAI/MAGNUM PHOTOS

The rebuilding of a temple that may never have existed on the site of a destroyed mosque in Ayodhya is part of a larger, decadeslong attempt by Hindu nationalists to recreate India in their own image

Ayodhya, under the dirty gray monsoon sky, was a surprise and a disappointment. All the way to this town in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, the most populous, largest, poorest, and possibly most violent state in one of the most violent countries in the world, the promise of change had been insistent. It lay behind me, in the sheet metal cordoning off the heart of New Delhi and demarcating the $2 billion Central Vista project that will erect a new parliament complex and a new residence for India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. It glittered on the edges of the pristine, mostly empty airport at Lucknow, where I had flown in from Delhi, and along the freshly tarred highway that took me, in a four-hour drive, from Lucknow to the town of Faizabad. Most of all, it lay ahead, in Ayodhya, Faizabad’s twin town, where Modi and his cohort of Hindu-right political groups are building a grand temple to the Hindu god Ram on the site of a destroyed mosque.

In October 2022, the new parliament will be complete; in December 2023, the temple. In May 2024, Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—the political party that is the electoral wing of the Hindu right—expect to win national elections for a third consecutive term. In 2025, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the five-million-strong paramilitary organization that is the fountainhead of the Hindu right, will mark a century of existence. For a significant section of Indian society, all this, taken together, marks a beautiful convergence. It means that India is close to achieving its true self, a futuristic nation that has fulfilled, in spite of assaults by Muslims, communists, and the West, its grand promise as an ancient, supremely advanced, Hindu civilization.

The centerpiece of this millenarian fantasy is the 57,000-square-feet, three-story sandstone temple being constructed in Ayodhya. If the parliament complex is necessary to maintain the facade of India’s democracy, the temple is of far greater resonance. It consecrates, supposedly, the birthplace of Ram, the blue-skinned, man-king-god who is the troubled protagonist of the epic poem Ramayana composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE. Given that the temple is being built on the ruins of a 16th-century mosque—the Babri Masjid—constructed by the Mughal dynasty just coming to power then in the Indian subcontinent, the temple is intended as a mark of Hindu supremacy in India and perhaps of the beginning of the end of the Muslim presence here. As a local RSS official called Dr. Anil told me one morning, humanity itself originates in Ayodhya. Here is where the first man Manu was born after the great flood, along with the first woman Satrupa, he said. This is where Ram was born, the ideal king of a utopian kingdom—Ram rajya—that will soon be revived on the Indian subcontinent.

And yet when I visited in August, Ayodhya-Faizabad was nothing more than a warren of muddy, waterlogged lanes and squalid buildings, the Ram temple just another hoax of the sort India has served up in plenty over recent decades. A model of the temple sat under a glass box in the reception of the hotel I was staying in. An ochre-colored complex of cupolas and spires, it appeared generic and unimaginative, completely adrift from the glorious temple architecture historically found in India. It is being designed by a Gujarat-based family close to Modi that specializes in contemporary Hindu temples, among them one in New Jersey raided last November by the FBI for using forced labor.

The hotel itself wallowed in sullen suspicion of its guests. The Canada-resident Indians who owned it had turned the white, once-elegant mansion—belonging to a former socialist legislator who had been defeated in 1948 by a Hindu right smear campaign about his atheism—into a shabby sequence of rooms, the large windows in the corridor firmly shut against the red-bottomed monkeys marauding along the rooftops. The Wi-Fi worked, but only near the reception. There was no bar. Meals were served only in the rooms, and the bathroom floor was uneven, collecting runoff water from the shower and clumps of the plentiful mud I tracked back from outside.

The streets outside weren’t much better. Apart from SUVs muscling their way through the chaotic traffic and the occasional smartphone in the hands of a passerby, nothing seemed to have changed over the past half century. The Muslim driver, a boy in his late teens whose only glimpse of a world beyond came from a brief stint driving trucks between Lucknow and Delhi, voiced his despair quietly as he guided the car through the streets. He wanted to get out, he said, but he didn’t know how.

He drove me around and showed me the sights available for those who couldn’t leave. There, he pointed out, was the afim kothi—the opium house—a haunted ruin of a mansion with crumbling boundary walls that marked the arrival of British colonialism in the late 18th century. The opium the peasants had been forced to cultivate had been exported to China, the descendants of the impoverished peasants shipped as indentured labor to Fiji and the Caribbean. Across from the opium house was the postcolonial Indian state’s contribution to the memory of this violence, a vast, open dumping ground littered with garbage.

We moved on. There was the Gulab Bari—the Pink House, characterized today by blackened onion domes and minarets, with echoing corridors where young Muslim men and women took selfies and a lone fakir silently contemplated the ineffable. A mausoleum for the 18th-century Shia Muslim monarch Shuja-ud-Daulah, it was built at a time when Faizabad had briefly been capital of Awadh, a tributary state to the Mughals. And there, finally, was the muddy brown Ghaghara river, which is called the Sarayu when it touches Ayodhya on its journey downstream. Ram had drowned himself in the Ghaghara around here, I was told; the temple to our left marked that event.

Rain came down hard on the new, slippery concrete paving the riverbank. People—priests, attendants, their families—napped inside the temple complex. Young men loitered outside, trying to find some pleasure in their surroundings, while ragged children scurried around selling peanuts and flowers. Most of all, the promenade seemed to belong to the cows, protected by a Hindu-right law that promises punitive measures against anyone “endangering their lives,” a piece of legislation that has resulted in roving lynch mobs targeting those suspected of bovine endangerment. Bony, whitish, and dirty, the cows were scattered everywhere, depositing their shit wherever they wanted. I stepped on a pile of cow shit and went down. The driver helped me up and we stared at each other in silent, mutual, despair. There was nothing to say.

In 1984, with only two members in India’s nearly 600-strong national parliament, the Hindu right seemed to have reached a terminal point in its turbulent history. Hindu political organizations had proliferated in the early 20th century under British rule, the most significant of them being the RSS. Funded and led by upper-caste men, the RSS combined ideas of Hindu revival spread by people like the late 19th-century monk Vivekananda with the racial theories increasingly popular in the west in the 1920s. M.S. Golwalkar, who became chief of the RSS in 1940 (and who is named by Modi as a major inspiration in his book Jyotipunj, or “Beams of Light”), wrote approvingly of Germany’s “purging the country of the Semitic Races—the Jews,” and urged Hindus to manifest a similar “Race Spirit” in regard to Muslims.

The end of colonialism in 1947 and the traumatic partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan allowed the Hindu right to carry out violent purges in areas where Hindus were a majority. At least a million people were killed, millions more displaced, hundreds of thousands of women and girls sexually assaulted, with Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs all caught up in the spiral of suffering and hate. But soon after these traumas, the RSS appeared to run aground. On Jan. 30, 1948, a Hindu extremist shot Gandhi dead for being too conciliatory toward Muslims and Pakistan. Although the RSS claimed that the assassin was no longer an active member of the organization, it was banned for a brief period and disappeared from mainstream public life.

As it turned out, being underground agreed with the RSS’s cultlike tendencies. Even after the ban had been revoked, electoral maneuvering was left to its political front, the Jan Sangh—which morphed into the BJP in 1980—while the RSS focused on its ideal of building a patriarchal Hindu nation. It recruited boys between the ages of 6 and 18, using doctrinaire lectures, a distinctive khaki uniform, and a routine of paramilitary drills to mold their “Race Spirit.” Individuals can be members of both the RSS and the BJP, and the latter’s top leadership, including Modi, inevitably worked in the trenches with the RSS before making the move into parliamentary politics.

It was a combination of decadeslong deep organizing with a massive public campaign that finally overcame the Hindu right’s consistent electoral failures and handed it the keys to India. In December 1949, just as the Hindu right was emerging from the backlash that had followed Gandhi’s assassination, a Ram idol appeared mysteriously inside the Babri Masjid. The Hindu right’s version of this story was that Ram had manifested himself to seize back his birthplace; the more prosaic truth is that a Hindu monk from one of the most powerful monasteries in the area snuck the idol in, aided surreptitiously by sympathetic Hindu government officials. As tensions rose, heavy iron padlocks were placed at the mosque gates. A complex legal dispute followed, with Muslims as well as three rival Hindu monastic orders claiming the right to worship in the structure while idol and mosque slumbered more or less undisturbed through the coming decades.

In 1984, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad—the World Hindu Council—demanded that the mosque be torn down, claiming that Muslims had destroyed an ancient temple that commemorated the spot as the birthplace of Ram and built the mosque on top of it as an act of deliberate humiliation. There is no historical evidence that Ram existed; that present-day Ayodhya coincides at all with the celestial Ayodhya spoken of in the Ramayana; or that any other temple previously occupied the spot where the Babri Masjid was built. But the VHP—one of numerous Hindu right groups affiliated with the RSS—was undeterred by these factual hurdles and demanded that a temple to Ram be built at the site. By 1989, its temple campaign was in full swing, with donations and shilas—bricks—being solicited from all over India and the wealthy Indian diaspora in Britain and the United States. Bricks to build the temple, some of them made of gold, wound their way across the country toward Ayodhya in long, ceremonial processions that were inevitably accompanied by violence. When the national elections took place that year, the BJP’s share of parliamentary seats rose from 2 to 85.

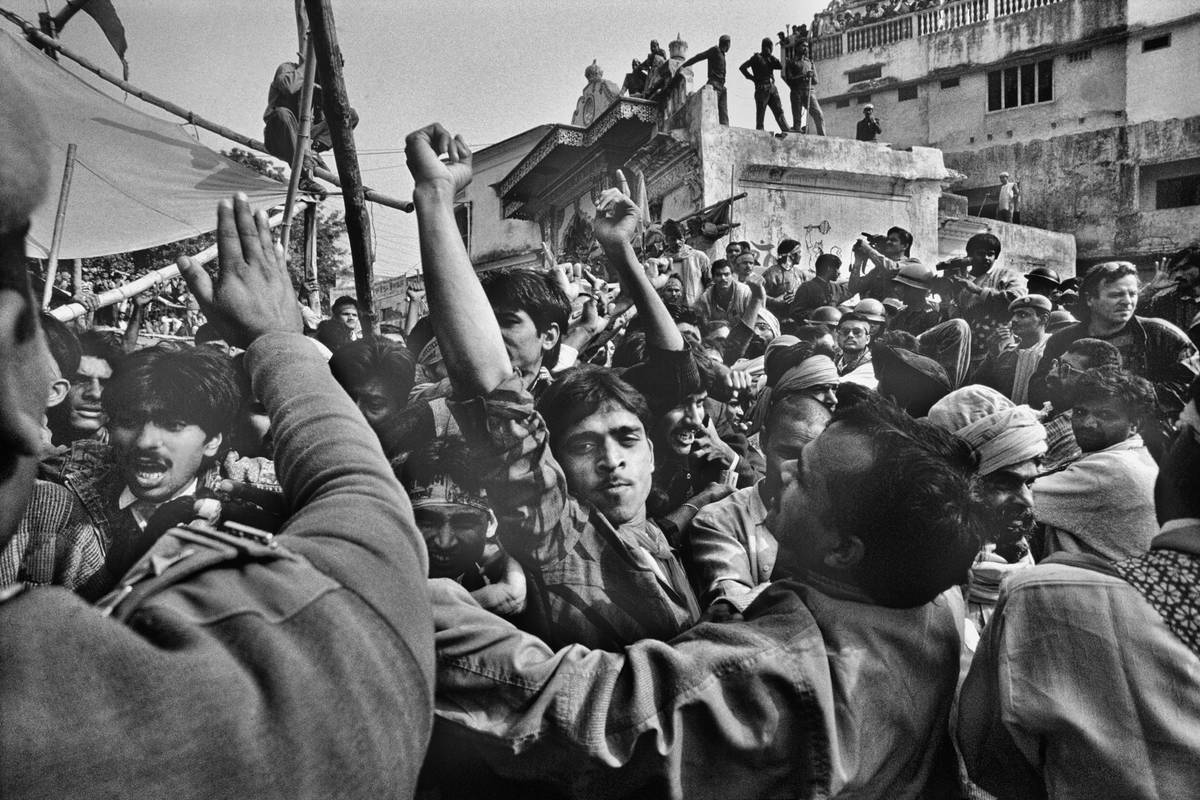

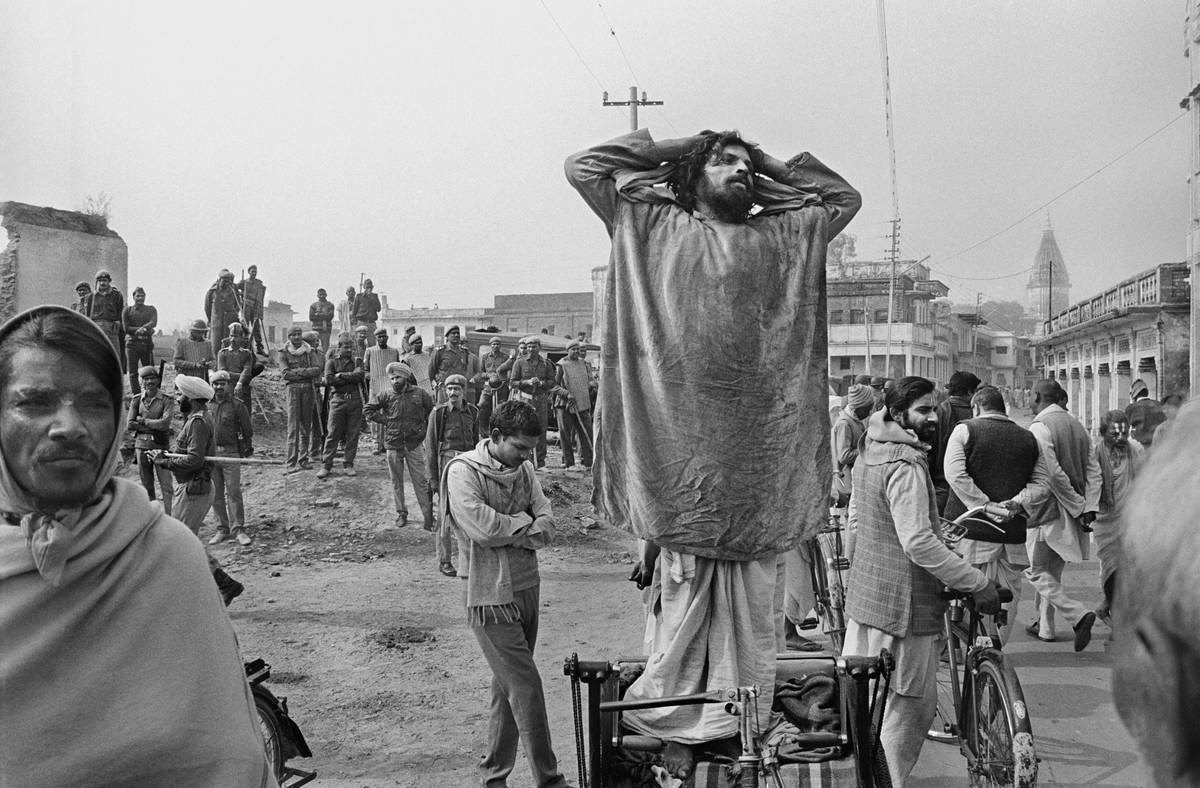

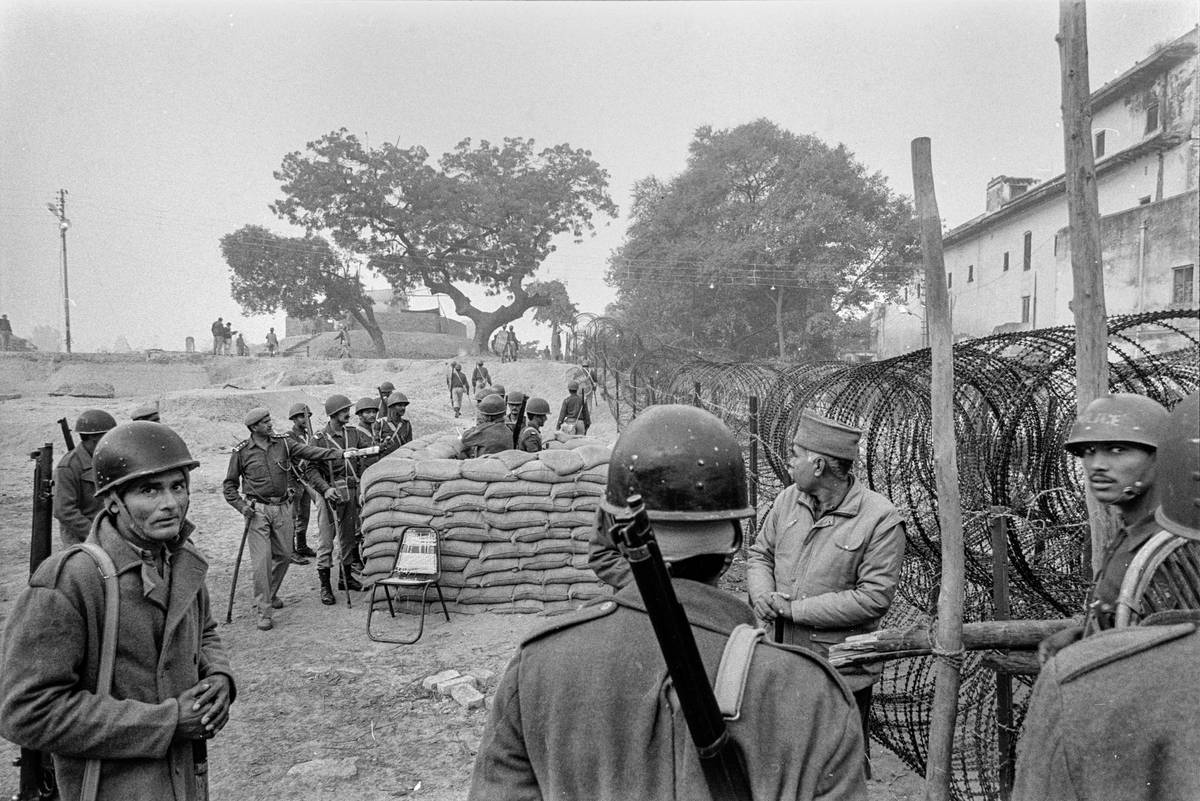

By the next fall, the temple-building campaign had moved up another notch. On Sept. 26, 1990, L.K. Advani, the avuncular-looking president of the BJP, began a symbolic rath yatra—a chariot procession—across the country in a Toyota pickup outfitted as an ancient Hindu chariot. His starting point was Somnath, a town in Gujarat some 6,000 miles southwest of Ayodhya where a Hindu temple had been sacked in the 11th century by a Muslim ruler from Ghazni, in present-day Afghanistan. The man in charge of organizing the procession was Narendra Modi, captured in photos as a brooding presence on the Toyota chariot. Like the procession of bricks, Advani’s chariot and the kar sevaks or volunteers who planned to build the temple with their bare hands provoked sectarian rioting in the cities, towns, and villages they passed through. Advani was arrested before he reached Ayodhya, but kar sevaks already in town stormed the Babri Masjid on Oct. 30. The ensuing police response led to the deaths of 16 men, according to the official account, while the Hindu right claimed that more than 50 had been killed. Riots broke out all over India while the BJP withdrew support for the coalition government then in power in Delhi. When a fresh round of national elections was completed in the summer of 1991, the BJP increased its tally of parliamentary seats from 85 to 120.

The increasing electoral success of the BJP against the backdrop of escalating violence meant there would be one final move in this phase of its temple campaign. On Dec. 6, 1992, while Advani and leaders of the BJP watched from a nearby rooftop, members of the Hindu right rushed the barricades around the mosque just as they had done two years earlier. Their numbers, this time, were far greater; the police were now partly intimidated and partly sympathetic to their cause

Grainy footage from the time is available from the Indian television program Eyewitness and its reporter, Seema Chishti. It is just past noon, and thousands of men, some saffron-clad, clamber over the fence, banging away at the three domes of the mosque with whatever they have at hand; rocks, picks, hammers. In contrast to an early morning demonstration by RSS volunteers—purposeful, military—this is a crowd in a state of frenzy. Nevertheless, there is enough forethought to carry out the Ram idol and its canopy before attacking the mosque. It takes two hours for the first dome to collapse, another 90 minutes for the second dome to be brought down. In six hours, the entire mosque has been leveled to the ground.

Dr. Anil appeared to think of this transformation in his father as only natural, the coming to life of a higher principle. “When Ram was here, there was no Islam, no Christianity,” he said. He would expand on that idea later, but that morning he was in a hurry to get the essential points of his life across. He himself had been loyal to the Hindu right from the beginning, starting as a member of the student wing of the BJP and eventually joining the RSS. Now he was the Prant Prabhari—the area chief—of the Rashtriya Muslim Manch, the Muslim wing of the RSS.

He seemed particularly proud of two achievements in this capacity. He had organized a ceremonial meal where Muslims had been served milk and fruit instead of biryani, the Persian-influenced dish of rice and meat more common on festive occasions. “Meat, fish, the eating of these things is a sin,” he said. In the switching out of meat for fruit and milk, he clearly felt that he had in some sense briefly liberated the Muslims from their sinful existence and converted them into upper-caste, vegetarian Hindus. He had also convinced local Muslims to donate money for the construction of the Ram temple. “The soil is India,” he explained. Ram was the ideal Indian, they were Muslims living in India: Where was the contradiction?

I hadn’t known that the RSS had a Muslim wing, and I didn’t know quite what to make of Dr. Anil. Slight, balding, with a gentle paunch and lively eyes, he didn’t project the violence I associated with the RSS. He was a Kshatriya—the warrior caste—but it was hard to take him seriously as a combatant. He laughed a lot, although never at himself, and a boyish self-satisfaction radiated from him, remarkable for a man in his early 40s. He had arrived at around 8 in the morning in my hotel room carrying a motorcycle helmet, the very persona of a busy professional who started his days early and worked long hours. Dismissing my offer of tea because he was required, as an RSS man, to avoid all intoxicating substances, he filled the ugly, airless room with his soundbites: “The RSS is purely interested in the development of the nation, not individuals”; “The RSS is not a political party. It does not depend on the BJP”; “There is no casteism in the RSS.” To this, he occasionally added the specifics of his personal story. The “doctor” referred to his Ph.D. in library and information sciences. He now worked as “guest faculty” at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia University (a university named after an anti-colonial, socialist politician). He also owned a computer and photocopying business near the university.

It was possible to read these details as characteristics of an entrepreneurial multitasker dabbling in politics, education, and business, someone exemplifying the energies that have been unleashed in Modi’s India. But then, there was the fact that, like almost everyone else I sought to interview, Dr. Anil came to the hotel room because there was nowhere else to meet in Faizabad-Ayodhya, no cafés or bars or restaurants offering the possibility of a social life. His guest faculty position had been terminated 15 days earlier because he had come to the end of a four-year contract; he had massive debts and his business wasn’t going well; he had pulled his daughter—the youngest of three children, the other two being boys—out of school because he didn’t have money for the fees and didn’t believe she was learning anything anyway.

The harsh truth about Ayodhya seemed to be that very little had changed there for the better even if the temple-building campaign had made its effects felt all over India by fueling the rise of the Hindu right throughout the country. Modi, in particular, seized on it, taking its combination of violence and spectacle further by giving it the distinctive stamp of his paranoid personality. In February 2002, on the 10th anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid, 59 kar sevaks returning from Ayodhya to Gujarat were killed in a fire engulfing the compartment of the train they were traveling in. Later investigations suggested that the fire might have originated from a malfunctioning cooking-gas cylinder. The Hindu right blamed it on Muslims, some of whom had quarreled with the kar sevaks at the railway station just before the fire erupted. Modi, who had recently become chief minister of Gujarat, was accused of unleashing a series of riots in the state where nearly 800 Muslims were killed and 150,000 displaced.

In 2014, Modi, proudly flaunting this record of anti-Muslim violence, won the BJP the national elections and became prime minister. A second, even more emphatic, victory in 2019 was anointed by India’s Supreme Court in November with a judgment that gave the government the go-ahead for the building of the Ram temple.

On Aug. 5, 2020, while the coronavirus raged unchecked in India, Modi, dressed in shiny, flowing clothes and a white KN95 mask, carried out a long ceremony inaugurating the construction of the temple. While images of Ram and a model of the temple were flashed in front of diaspora supporters gathered in front of a giant screen near Times Square, Modi offered prayers to the Ram idol and the 88-pound silver brick that will serve as the keystone of the foundation. Addressing a subsequent gathering of Hindu-right grandees, many of them dressed in the distinctive saffron that is meant to mark the detachment of the Hindu ascetic from all worldly affairs, Modi did not forget to mention that along with Hindu pride and assertion, the temple would also bring massive economic development to the region.

The one area in which Ayodhya does seem to have grown is as a pilgrimage destination for rural pilgrims who are directed with casual brutality through metal barricades by armed policemen in khaki. Past shops selling sweets and flowers the pilgrims went, hustled by ravenous-looking men offering to be guides, past the competing shrines of dueling monasteries, the most prominent of them the steep, fortresslike shrine of Hanumangarhi that sits on the outer perimeter of Ramkot, the mythical fort of Ram. Beyond, behind more barricades and guarded by more armed police, lay the disputed center where the new temple was being constructed.

Had a great Hindu temple to Ram ever previously existed here? The claim is a surprisingly recent one. In 1990, B.B. Lal, an archaeologist who had conducted digs around the mosque in the mid-’70s and reported little of significance, suddenly claimed in a Hindu-right magazine that his excavations had actually revealed temple pillars predating the mosque. Lal went on to have a fruitful post-retirement career, publishing evermore speculative books asserting that Ram was a historical person and receiving two of the highest civilian awards in India from the BJP government in 2000 and 2021.

In 2003, another dig, ordered by the courts, began on the site of the demolished mosque. The dig was carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), a state body that reported to the BJP-led government in Delhi. Khalid Ahmad Khan, a septuagenarian who had been a member of the Muslim alliance opposing Hindu claims on the land, had described the dig to me in his house the previous day. Khan had been present as an observer on behalf of the Muslim petitioners, the court-appointed arrangements displaying a portentous attention to balanced representation; 33% of the 51-member team from the ASI had been Muslim, with the same proportion of Muslim labor chosen for the actual digging. The 2003 dig, according to the report eventually filed by the ASI, uncovered material going back as far as the 13th century BCE, including “glazed pottery, tiles and bones.” But the ASI’s main contention was that “a massive structure” existed at the site “from the 10th century” CE on top of which the 16th-century mosque had been built, and that the “remains” recovered of this 10th-century structure contained “distinctive features found associated with the temples of North India.”

Khan did not believe that the material found provided evidence of a Hindu, as opposed to a Buddhist or Islamic site. Surrounded by voluminous files of legal documents and newspaper clippings, he gave the impression of clinging to the illusion of democracy and constitutional principles against an ever-encroaching reality. Anxious to assert his loyalty to India and his cordial relations with the Hindu religious leaders, Khan told me that the Hindu argument had been based entirely on faith and belief. The Muslims, however, had depended on evidence. “We produced revenue records, government affidavits, and artifacts. They said their records had been destroyed. I was there during the digging. They found no proof.”

Vineet Maurya, another opponent of the temple whom I had met in my hotel was also skeptical of the Hindu temple theory. Maurya, who converted in his youth from Hinduism to Buddhism, was engaged in a legal dispute with the government about its forcible acquisition of his family home in Ayodhya as part of its expanded temple complex. Maurya, who came from a family of agricultural laborers, had belonged to one of the castes at the bottom of the hierarchy. His break with Hinduism had been accompanied by a long journey of educating himself. He had a law degree, was learning Pali so he could read Buddhist texts, and was studying for a master’s degree in ancient history from Awadh University. He believed that the oldest civilizational artifacts discovered at the site were Buddhist rather than Hindu, and as such the site should be turned into a “national monument” that brought in tourists and pilgrims interested in India’s Buddhist past.

Given that the area in the sixth century BCE had been a Buddhist center of some repute called Saket, it is quite likely that a Buddhist structure had indeed existed on the site. It could also be that a Hindu temple was later established on the site as Buddhism was pushed out of India. But this temple would not be older than the 10th or 11th century CE, and it featured, according to the ASI’s own report, gods and goddesses other than Ram. Except in the Hindu right’s colorful murals and popular television skits, no one seems to know quite what happened between the 10th and the 16th centuries, when the Babri Masjid came up. It is quite possible, for instance, that the large mosque was built on top of a smaller Islamic place of worship, which could indeed have been built on a Hindu temple built on top of a Buddhist structure.

The ASI report itself had noted defensively of its “evidence” that its work had been done hurriedly and under difficult circumstances, including heightened security checks, torrential monsoon rains, and monkeys who made a mockery of the court’s directions to preserve materials “under lock and seal.” The Supreme Court judgment in 2019 that granted the site to Hindus spent an enormous length of time going over the arguments and counterarguments of the ASI report. The judgment, in keeping with the verbose nature of the Indian judiciary, is over a thousand pages long, filled with floral asides that bring in comparisons to ships and corporations to decide if Ram can be considered a “legal personality,” with references to Wordsworth, Karl Popper, and the “distinguished archaeologist, Sir Mortimer Wheeler” thrown in.

As significant as the verbal excess of the judgment might be its extratextual aspects. The five-judge bench delivering it was headed by Ranjan Gogoi, who had been appointed as chief justice of the Supreme Court under the Modi government a little over a year earlier, in October 2018. Hounded by accusations of sexual harassment and persecution by a junior employee, Gogoi went on to deliver a series of controversial verdicts in favor of the Modi government, including the removal of a special provision for the Muslim majority in Kashmir and the creation of a register that targeted Muslims in Assam and stripped at least a million of them of their Indian citizenship. Eight days after delivering the Ayodhya judgement, Gogoi retired from the Supreme Court. Within four months of his retirement, he was nominated to the Rajya Sabha—one of the two houses of the Indian legislature—by Modi’s government.

“There is no specific finding that the underlying structure was a temple dedicated to Lord Ram,” the Supreme Court judgment conceded. It also agreed that the demolition of the mosque had been illegal and that the Ram idol had been smuggled illegally into the site in 1949. Nevertheless, on the basis of “documentary and oral evidence,” it decided, in tortuous prose, that the “faith and belief of Hindus since prior to construction of Mosque and subsequent thereto has always been that Janmaasthan of Lord Ram is the place where Babri Mosque has been constructed which faith and belief is proved.” It ordered the site to be handed over for the building of the temple, while an alternative location, on the outskirts of the town on the highway to Lucknow, was to be given to Muslims for a new mosque, to replace the one that had been destroyed.

One afternoon, I went to meet Dr. Anil at his copy shop. We were planning to travel to Karsevakpuram, the Ayodhya neighborhood that has gone from being a temporary encampment for kar sevaks in the ’90s to becoming a permanent feature of the town. But elections for the Uttar Pradesh legislature were to take place in February 2022—which the BJP would go on to win on March 11—and Dr. Anil needed me to wait until a television crew had arrived to interview him. We waited in the shop, a cubicle dominated by a photocopy machine and a desk holding a computer and printer. Generous cracks ran across the unpainted floor, dust sat on open shelves built into the wall, and brown plastic stools served as chairs, the brand name stickers still attached.

When the television crew arrived, we stepped out and went over to the edge of the highway. The name of the channel, according to the burly, bearded producer, was Newsprint. It wasn’t a joke. He was earnest, maybe slightly evasive as he told me the channel was based in Delhi and uploaded directly onto YouTube. I wondered if it was part of the Hindu right’s fecund disinformation network of talk shows, trolls, and WhatsApp groups, and if the intention behind filming outside was to create as much of a public spectacle as possible. Later, when I searched for the channel on YouTube, I couldn’t find it. In the moment though, the afternoon sun down beating down on the television crew and its subjects, the interview seemed both elaborately contrived and deeply revealing of conditions in Ayodhya.

The BJP was seeking reelection in the place that had changed its political fortunes, where a utopia once existed, where—according to a pamphlet widely available in Ayodhya—virtuous Hindu men and women lived in sky-high mansions where the floors were heaped with gems. I took a look at my surroundings. Across from me, the Buddhist-inspired domes of the Ram Manohar Lohia university offered a faint reminder of other histories of the region. And yet all pasts seemed irrelevant against the distressing reality of the present.

What else was the entire project of Ram rajya other than endless symbolism evoked to obscure tawdry reality?

None of this appeared to have any purchase on the interview that unfolded, the knot of people around the camera caught in billowing dust and exhaust from passing vehicles. The gathering was still small, but there was a practiced TikTok flourish to the young reporter as he began, twisting his body into a V and pivoting on his sandals as he held the mic in one hand and gestured with his other at the people gathered around. First in line was Dr. Anil, confident in his pronouncements. He was followed by a man called Haji Syed Ahmed, a member of the Muslim wing headed by Dr. Anil. Ahmed, too, spoke in sound bites, confident of the good work being done by the Hindu right, although the most distinctive thing about him was his elegance in that crowd of slovenly Hindu men. He wore a long gray kurta, white pajamas, and stylish blue sneakers. His neatly trimmed beard, his white skullcap, and blue checkered keffiyeh indicated his status as a devout Muslim, as did the adjective “Haji” before his name. Earlier, he had told me a convoluted story about his shop being forcefully occupied by another man with political connections and his hopes that the Hindu right would be able to get it back for him. He was, he admitted sorrowfully, more or less ostracized by other Muslims for his overt support of the Hindu right. There were others Dr. Anil had summoned to give their views, including a Muslim woman in a hijab who was distracted from the interview by her restless toddler children.

The lovefest for Modi and Yogi looked like it would go on forever, but two passersby decided to intervene. Both men appeared to be supporters of the SP, confident and articulate in spite of being vastly outnumbered. The BJP’s cow protection laws had resulted in feral cattle running wild and destroying crops in the fields, one of the men shouted. His companion, younger, more cerebral, responded to his hecklers with verve, talking about the corruption of the Hindu-right politicians whose names could be found in the Paradise Papers. The reporter got increasingly flustered, as did Dr. Anil. At the university across, classes had ended, and students slowed down on their way home to listen. A few were women, but they did not linger long. The Muslim woman had departed with her children, without speaking, and it was almost entirely a male crowd gathered now around the television crew.

Although it was all talk, there was a physicality to the scene, the height and burliness of the Yadav men offering a challenge that could not easily be quashed. The crowd got larger and louder, and small, independent quarrels began to break out on the edges, Dr. Anil struggling to be heard above the noise as he faced the camera once again. Another big man entered the scene, his political affiliation obvious from his Brahmin’s topknot. I got the impression that he had been summoned there to wrest the initiative back, which he did by ignoring all questions from the reporter and raising his voice in a chant. It was the war cry of the Hindu right coming out of his mouth, the same one that had resounded in the air the day the Babri Masjid was demolished, the same one that Muslims hear when pogroms break out, that clogs the television channels and social media networks in India as prelude or punctuation to a vitriolic outpouring of abuse. “Jai Shri Ram,” he shouted, and “Jai Shri Ram,” the crowd responded, tentatively at first and then louder by the moment. The Yadav men laughed, shook their heads disbelievingly, and exited the scene.

Another billboard featuring the Modi-Yogi combine graced the entrance to the site where the bricks gathered in the nineties are kept. It was hard to believe that these were the shilas gathered from all over India and abroad, blessed by priests in Sanskrit and trucked to Ayodhya in ceremonial processions of kar sevaks displaying unsheathed swords. The place had the feel of a storage shed, with waterlogged ground crisscrossed by policemen changing shifts, elderly kar sevaks in saffron dhotis going out for evening walks, and monkeys foraging for food. The bricks were stacked in untidy columns against the walls, along with elaborately carved columns that seemed to belong to some forgotten 1.0 version of the Ram temple.

Promises had been made that the bricks would be used for the temple being constructed, but it seemed unlikely that more than a few would find their way there. And yet what else was the entire project of Ram rajya other than endless symbolism evoked to obscure tawdry reality? A temple stood in the center of the yard, but it was not the temple that caught the eye as much as the murals decorating its outer wall. History had been turned there into a singular story of the oppression visited upon Hindus and their courageous resistance: Cruel-looking men in vaguely Arab outfits brandished swords and fired cannons at the temple supposedly torn down to make way for the Babri Masjid; next to them, the Sikh reformer Govind Singh was busy fighting on horseback, a deft touch meant to draw the Sikhs into the Hindu right project; below, the faces of two brothers from Kolkata killed in the police firing of 1991 looked out, the calm resolution of their faces borrowed from iconic representations of Indian anti-colonial revolutionaries.

Karsevakpuram itself was different, the symbolism held in check for the quieter machinations of power. It housed the offices of the VHP, which had fronted the assault on the mosque. Armed sentries were on duty around the large complex, neat and quiet, with flowers and well-watered lawns. It was the first time since I had been in Ayodhya that I felt a sense of order, and with it came the sensation of being in close proximity to authority.

Fifteen Hindu men comprise the committee in charge of the construction of the temple, which is already mired in controversy. A vast amount of the money donated for construction—there are pictures of Modi soliciting money for the temple throughout banks in India—is said to have been siphoned off. Land near the temple had allegedly been acquired by a close relative of a senior BJP functionary and then flipped over to the temple trust at many times the purchase price. A member of the temple trust committee had also apparently rented out offices to Larsen & Toubro, the Indian engineering firm—the name harks back to the Danish men who started the original, colonial-era company—constructing the temple pro bono.

I had tried talking to this member. His name was Dr. Anil Mishra, the doctor in this case referring to his homeopathic practice. Mishra, who had apparently installed an elevator inside his multistory home to signal his newly acquired affluence, sounded alarmed when I called him. I should talk to his colleague Champat Rai, general secretary of the temple trust committee, he said. He himself was unable to tell me anything. I was unsurprised by Mishra’s refusal to talk to the media. The Hindu right, which refers to journalists as “presstitutes,” is choosy about who it grants access to and what it reveals. But Dr. Anil—the original one—was confident that he could introduce me to Rai, and so we loitered inside Karsevakpuram, the quiet of the evening occasionally interrupted by monkeys jumping from rooftop to rooftop.

A convoy swept in, white SUVs disgorging men in crisp white clothes, the policemen and hangers-on attentive. Dr. Anil suddenly appeared diminished, but I could also see something of his determination as he attached himself to the men striding into the main office, introducing first himself and then me. I could sense the shimmering outline of a system built entirely on patronage and influence and that Dr. Anil’s stock had perhaps risen subtly because, in spite of his modest motorcycle, his failing copy shop, and his truncated position at the university, he had brought a journalist from the United States with him to this place.

Inside the office, Rai listened to my request for an interview, his smooth, clean-shaven face animated by something that could have been suspicion, or fatigue, or both. An Indian man wearing jeans was introduced to me as a North American working for the Hindu cause. We made small talk about New York. “I have no time for you today,” Rai said finally. “But tomorrow, I can give you 15 minutes. Come here at 5 p.m.”

The next evening, I waited for nearly an hour at Karsevakpuram. Neither Rai nor any of his entourage showed up. Instead, I found myself chatting with a man called Hazari Lal who sold incense and ayurvedic medicine at an exhibition hall near the front gate. A giant model of the Ram temple sat under bright fluorescent lights, beige rather than the ochre chosen for the version under construction. A large photograph of Ashok Singhal, the VHP president at the time of the demolition, squatted in front of the model, the base of the temple cluttered with random slabs of marble and what I assumed were consecrated shilas. Paint had flaked off in patches from the yellow guard rail around the model and the pink walls of the hall. A raised relief map of the temple site occupied the outer perimeter of the model; apart from a few yellow blocks indicating buildings, the rest was unpainted concrete, as if the maker had become exhausted halfway through the project.

Lal, insisting that I sit with him, brought plastic chairs out into the open so that we would see Rai if he showed up. Lal had been a kar sevak during the attempt to storm the Babri Masjid in 1990. Two years later, he returned for the successful assault on the mosque. He described climbing up to one of the domes and of falling from it, injuring his head and fracturing his left hand. He had been imprisoned for two weeks for his part in the demolition and then released on bail. Beyond that, there had been no legal repercussions for his actions.

There was no guilt, no self-consciousness, in Lal’s telling of the story. The mosque and Muslims were a foreign imposition to him, and his world, apart from that spectacular outburst in the early ’90s, appeared to have been largely side-stepped by modernity. Although only in his early 60s, he gave the impression of being an old man, aged according to the calendar of impoverishment that holds sway over so much of life in this part of India. There were hints of personal tragedy, of a son who worked in a factory and whose little girl had died. When he posed for a picture for me or took out an old mobile phone to ask me to enter my number on its tiny keypad, I got the sense of a man mimicking what he had seen others around him do, which is probably why in spite of his violent past as a kar sevak and his proximity to power, he evoked mostly vulnerability. His right eye was opaque with a cataract. I recalled how the previous day, he had asked Dr. Anil if he could help him find a clinic where the eye could be checked out. Dr. Anil had been pleasant but noncommittal. Later, he had compared Lal to Rai. “Some have the capacity to rise, others don’t,” he had confided to me. “That is the only difference between men.”

One morning, as I made my way into the heart of Ayodhya with Dr. Anil, we bought pedas—round hard discs of sweet cream that look like cheese—as an offering from a sweet shop owned by one of Dr. Anil’s Hindu-right colleagues. We left our slippers there for safekeeping as well; our phones and wallets we had already given to the driver of the car, waiting in a parking lot on the edge of the pilgrimage zone. It was early but already crowded, the pilgrims clustered in front of Hanumangarhi, where three streets converge in a blur of noise and color.

The ground was slimy under our feet as we climbed up to the shrine of Hanuman, the monkey god. A beloved, all-action figure in the Ramayana, where he is Ram’s most devoted ally, Hanuman too has morphed in recent years into an icon of violent Hindu masculinity. He is now visible everywhere, particularly on motorcycle windscreens and the rear windows of cars, as “Angry Hanuman,” a contorted face in saffron and black that went viral after Modi praised the design at an election rally in 2018.

Modi, accompanied by Yogi and trailed by bodyguards and a television crew, had visited the Hanumangarhi shrine in August 2020 after the Ram temple ceremony. He had used an alternative entrance, one that allowed him to avoid the climb. The shrine had been emptied out for him, and he had stood directly in front of the Hanuman idol, swirling a lit lamp and muttering a prayer.

Ayodhya, India, 2022. Crush of devotees at the Hanuman Ghari temple.RAGHU RAI/MAGNUM

We had no such luck. We climbed the 200 steps, on top of which a sign announced “Only Hindus May Enter.” In front, a crowd jostled to get closer to the shrine, priests leaning down from the inner sanctorum to accept their offerings. Dr. Anil led me into the press of bodies and glided away. I stood there amid the crush of bodies, uncertain of what to do. I could barely make out the features of the Hanuman deity. Later, when watching Modi’s visit on YouTube, I would get a sense of it, diminutive and aniconic, a far cry from Angry Hanuman. I held my bag of pedas up, found a priest willing to receive it, and then I was out of the crush, relieved.

Dr. Anil looked at me with surprise. “What did you do with the pedas?” he asked. He stared at me with astonishment when he heard that I’d given them to the priest but not taken them back, as I apparently should have. When I first met Dr. Anil, all I had told him was that I was a journalist based in New York writing a story on the Ram temple. Dr. Anil had come to the conclusion that I was a devout, right-wing Hindu all on his own. Now I could sense a hesitation, as if he was considering for the first time who I might really be. Standing with my back to the crowd, I felt a wave of unease. Just the day before, The Guardian had published a piece of mine on the Modi government’s practice of planting malware on the computers of activists and incarcerating them for years without trial under an anti-terror law.

But the moment passed. Dr. Anil, happy to have a chance to laugh at me, decided that I was merely displaying the ignorance of someone not born in the Hindu heartland. We went into the office area to try and find the head priest, a man whose Persian title of Gadd-e-nashin—Keeper of the seat—indicated the origins of Hanumangarhi in the time of Muslim kings. The Gadd-e-nashin was not in, however, and Dr. Anil led me to another priest, a gigantic man who sat on an open platform meeting devotees. I went through the motion of seeking his blessing, which he granted perfunctorily, tossing some flowers in my direction while waving a white, ceremonial whisk with the other.

Although Dr. Anil seemed inclined to introduce me to one senior priest after another, I persuaded him out of Hanumangarhi. In front of us lay the site of the future temple and the temporary shrine housing the Ram idol. Dr. Anil was disappointed that we were approaching it from the commoners’ entrance rather than through the VIP access route that allowed important people to drive right up to the gate and avoid the crowds. Instead, we waited in front of the security booth in a long, straggling line, exposed to marauding monkeys and touts hustling people to leave their belongings in lockers available at nearby shops. At Hanumangarhi, the pilgrims had been mostly poor and local, many of them women and the elderly. Now I began to spot urban, middle-class men who had come from southern India and Kolkata.

Through the security booth we went, stepping into a corridor enclosed above and to the sides by wired netting, like a bunker from which to monitor the position of an opposing army. An excitement animated the crowd as we progressed through the labyrinthine corridor, accompanied by the shouts of policemen asking everyone to keep moving.

Everyone slowed down again as we approached the temporary shrine. The idol was set well back from the pilgrims sequestered in the iron corridor, attendant priests handing out packets of consecrated sweets through an opening in the wired netting. I lingered as long as I could. After the decades of violence in the name of Ram, portrayed in memes as a muscular uberman, all veiny biceps and chiseled six-packs, the appearance of the idol, small, dark-skinned, and with big manga eyes, was unexpected. Because this was Ram’s birthplace, the idol was of an infant Ram—Ram Lalla—and just a little over 6 inches tall.

This was the god who had changed the fortunes of a nation. He had been smuggled in under the cover of darkness, in 1949, and hurried out amid the noise of a mosque being brought down, in 1990, a god placed here and there by his followers. Now, he looked like a doll sitting in a temporary dollhouse in front of a bunker inside a fortress. We had just seen the site of his future temple, marked by yellow earth movers stranded in the vastness of an empty square.

Not long after my visit to the temple site, I went to meet Dinendra Das, a member of the temple trust committee. Das is the mahant—head—of the Nirmohi akhara, a powerful religious order that owns temples and monasteries in a number of states in north India. It is one of the claimants to the disputed site in Ayodhya, but it has been sidelined by the Supreme Court’s decision that the Ram idol will be represented on earth by representatives of the VHP. Das’ presence on the committee seemed to reflect the compromise worked out by the Hindu right, where politicos like Rai and Mishra called the shots while the priests were kept onboard in symbolic positions.

I had been told that Das and his akhara were disgruntled with their secondary role, but Das revealed nothing of this discontent when I met him in his monastery. With his saffron garb and flowing grey hair and beard, he was far more personable in real life than the cross-eyed photo of his displayed on the temple trust website. It was obvious that his position in the committee, along with his status as an important religious leader, had brought some perks into his life. An official car was parked in the yard for his use, complete with government license plate and VIP lights. A personal bodyguard, a policeman in plainclothes, stayed present throughout my conversation with him.

Yet there was also a difference between him and power brokers like Rai as well as with aspirants to power like Dr. Anil. Das was far more awkward, flattered that a journalist from New York had arrived to interview him. There was something appealing about the transparency of his vanity, the way he adjusted his clothes when it was time for a photograph or the manner in which he conveyed to me that his favorite subjects as a college student had been English, economics, and Sanskrit. His original name had been Dinendra Kumar Pandey. Like all monks, he was required to dispense with his caste name and take on a common last name used by everyone. He became Dinendra Das in 1992, when he took his vows. In 2017, he became the mahant.

The wealth, ambition, and aspiration that the Ram temple had precipitated all around was more intermittent in its presence in the Nirmohi akhara. The mahant’s room was big and airy; the floor had been tiled recently and the ductless air conditioner on the wall was new and sleek. They were planning to rebuild the two other structures in the complex, grassy and overgrown, set back from one of the narrow lanes curling through Ayodhya. One building would be converted into a guest house for visiting devotees and monks. The other would be torn down for a new complex where the shrine would face outward, toward the road, in a concession to modern sensibilities that require even a deity to advertise its presence.

But if change was coming, indeed had already come, it had not yet made its full impact on the akhara. I was invited to lunch with the monks—the mahant ate separately—in the main building. It was in the old North Indian haveli style, with an inner courtyard around which the shrine and the quarters of the monks were arranged. The deity faced into this courtyard, and I was led past it by monks in their early teens who looked at me with curiosity. The kitchen was narrow, with old, high ceilings. The meal consisted of rotis and rice with dal and a vegetable curry.

We ate sitting on the floor, served by a muscular monk with a Brahmin’s topknot and a wicked sense of humor. When I apologized and said I hoped that they had not been waiting because of me—the interview with the mahant had gone on beyond their lunch hour—he replied, “You’re exactly the reason we’ve all been waiting with empty bellies.” There was no malice in the comment. When I later asked the assembled monks, ranging from the teenage boys to men in their 70s, how they had been affected by the coronavirus, the same man responded. “We’ve all come here to die,” he said, referring to the belief that by cutting off ties to family and the material world and living out their years on sacred ground, they had the opportunity to break the cycle of rebirth. “But god has a way of not giving people what they want,” he chuckled. “So those who want to live are dying, and those of us who want to die are living.”

Ayodhya is only the start of the liberation the Hindu right envisions for India.

There was something odd but endearing about a monastic order of childless men ostensibly devoted to taking care of a never-changing, never-growing infant. But these rituals of care were a long way from the Hindu masculinity I had seen in evidence all over Ayodhya. Khan, the Muslim opponent of the temple, had told me with some sadness that the Hindu right did not really believe that Ram was a god. “The temple is not being built to Ram the god but to Ram the ideal man, what they call ‘Purushottam Ram,’” he had said. This was certainly how Dr. Anil had referred to him. “Ram is not a common man. As a son, brother, cousin, his character is that of ‘Maryada Purushottam’,” he had told me on our first meeting. “Why do institutions today fail?” Dr. Anil had continued. “Why do we have murders and rapes? The writers of the constitution forgot our past. The constitution brings things from the outside. In Ram’s time, there were no locks in houses, no gates in temples. This temple will start that culture of Ram.”

And yet Ram the ideal son, brother, and king is a long way from the versions of him encountered in the many adaptations of the Ramayana that flowered in the Indian subcontinent and beyond through the centuries. Although he is the seventh avatar of Vishnu, and in that sense immortal, Ram doesn’t always remember his divine antecedents. Often, he struggles with events and actions and their consequences, and his life is, from one perspective, utterly tragic. Banished from Ayodhya because his father wants to appease his younger wife—Ram’s stepmother—who wants her biological son to inherit the throne, Ram is unable to prevent the abduction of his wife Sita while in exile. When he wins her back, after an epic war that involves the help of Hanuman and other monkeys, he is hounded by the suspicions of his conservative subjects that Sita has not remained faithful to him while in captivity. Even a fire test of purity by Sita cannot stop the tongues wagging, and Ram banishes a pregnant Sita to the forests. All this is the backdrop to his utopian rule. Even his death has a tinge of darkness to it, with Ram—at least in some versions—finally drowning himself in the river.

It is possible to argue that this very frailty and conflict in Ram endeared him to the spiritual traditions that rose around him. Often, the stories and songs composed and sung about him came from marginalized sections, from men of the weaver caste like Kabir and from women like Mirabai, people removed from direct access to wealth, power, and knowledge. But these approaches to Ram are a long way from the toxic version on display in Ayodhya and in India at large, a version that always tends towards Purushottam Ram.

I recalled how Dr. Anil, after the visit to the temple site, had been in a gregarious mood that appeared to have nothing to do with his having visited Ram Lalla. As we walked back past shops selling religious souvenirs, saffron scarves featuring the Angry Hanuman prominent among them, the conversation had turned, somehow, to Muslims. “They had their chance in 1947,” he said. “They wanted a separate Muslim nation and they got it. Why do they still stay on here?” They were mostly Hindus who had long ago converted to Islam. To stay on in India, they should reconvert, he believed. What if they wanted to be in India as Muslims? I asked. He shrugged. “What can we do? We can’t kill them,” he said. They should have their voting rights and any state benefits taken away, he believed. They could live and work in India no more. It was a horrifying vision, one that has already been put into place in Assam and was the other part of the culture of Ram that the temple would bring into being.

Earlier in the day, just before we visited the Ram idol, Dr. Anil had wanted me to stop by at an apartment he had bought as an investment. It was close to the center of Ayodhya, and he described to me how everything would be transformed once the temple was complete. The river bank littered with cattle sheds and shit would be converted into a promenade. Condominiums would come up everywhere, as would a new airport being constructed not far from his photocopying business. Devotees with dollars in their bank accounts would be whisked from Delhi to Ayodhya by air or a high-speed train. They would relax in luxury, seven-star hotels on the outskirts of the town and be driven along wide highways directly to the new Ram temple. The website for the temple offered additional details. Visitors would be able to enjoy a “special peace zone for deeper meditation,” gaze at a “Lily-pond [sic] and Musical Fountains,” and check out the VIP cousins of the cattle I had seen everywhere being pampered at the “Adarsh Goshala” shelter for cows.

The highways existed—I had been on them. But Dr. Anil’s apartment was at the end of a grim block of concrete—housing bearing the unmistakable stamp of being built for the lower middle class by a government agency. There were cars parked in front of the two-story buildings in a demonstration of the upward mobility that had come to Ayodhya. But the electric wires ran in manic fashion from rusting, crooked poles, the paint had peeled off the walls, and mildew grew like an alien infestation on the window ledges. Dr. Anil led me to his second-floor apartment, empty, still in the process of being finished. He spent a long time washing the stainless steel sink. Then he showed me the squat toilet, which he said had been relocated at considerable expense because it originally pointed in a direction considered wrong by the scriptures. Everything about the apartment and its surroundings was miserable, but Dr. Anil’s energy and optimism seemed boundless.

I could understand why. Ayodhya, after all, is only the start of the liberation the Hindu right envisions for India. In Varanasi—a city far older and much more central to Hindu traditions than Ayodhya—the Gyan Vapi mosque sits surrounded by barricades and policemen while the Shiva temple next door is expanded along lines similar to what is being done with the new Ram temple. There are demands to install an idol inside a mosque in the town of Mathura because it supposedly occupies the birthplace of Krishna, another avatar of Vishnu. There is even talk that the Taj Mahal is really an ancient Shiva temple appropriated by Muslims that must be returned to its former glory. The Ram temple coming up in Ayodhya, built with stone from Rajasthan, designed by an architect from Gujarat, funded by dollars from the diaspora in the West, is only the beginning of an effort to construct a past that never was, in the hope of devising a future from which India’s Muslim inhabitants can be erased.

Siddhartha Deb is an Indian author and journalist. His nonfiction book, The Beautiful and the Damned, was a finalist for the Orwell Prize and the winner of the PEN Open award.