by Taj Hashmi 10 February 2019

The “Language Movement” of erstwhile East Bengal/East Pakistan – presently, Bangladesh – was more than a language movement, it was a cultural-political movement for Bangladesh. No wonder, even after the Pakistan Constitution of 1956 had guaranteed Bengali as one of the two state languages along with Urdu, East Bengalis continued to mourn the deaths of half-a-dozen martyrs, who got killed by Bengali policemen at the order of a Bengali magistrate under a Bengali Chief Minister (Nurul Amin) of East Bengal on 21st February 1952. In 1956, the province became East Pakistan after the merger of all the four provinces in the western wing of the country as “West Pakistan”.

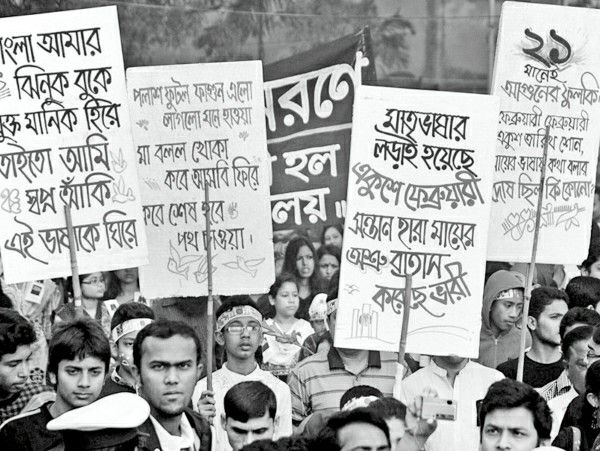

The Language Movement is a very important historical event, not only for East Bengal but also for the whole world to learn as to how cultural movements can steer a political one, with a long-term programme with patience, courage, integrity, and determination of the people concerned. The Language Movement, in short, is a glorious example of people’s determination. The leaders of the movement, who besides the politicians were teachers, writers, poets, journalists, and last but not least, students, who organized millions of youths for 20 years (1952-1971) in the most unique way by walking bare-footed early in the morning every 21st February on streets towards the Shaheed Minar (Martyrs Memorials) in Dhaka (and to the thousands of replicas across the country) and to the Azimpur graveyard in Dhaka where the martyrs lie buried.

It was simply a wonderful way of arousing patriotism and the sense of belonging to the Bengali Nation (which most East Bengalis never thought of as a requirement until the late 1960s, and finally in 1971) by organizing a political movement in the form of a cultural one, apparently to mourn the unjust killing of students and celebrate 21st February as a day of remembrance.

However, there is a flipside of the movement. Had West Pakistanis and their local agents in East Bengal been respectful to Bengalis, their culture and their entity as fellow Pakistanis, there would not have been any Shaheed Day celebration as Bengalis celebrate it since 1953. Observing or celebrating the victory for the Bengali language in 1956, and eventually, independence in 1971, began as a protest against West Pakistani hegemony, and step-brotherly treatment of Bengalis. What Sukarno could achieve in Indonesia, Jinnah failed to do so in Pakistan, miserably. The tone of his two speeches made in Dhaka as the Governor-General of Pakistan in March 1948 struck the “first nail” into the coffin of united Pakistan through protests, and eventually defiance of the authorities in February 1952.

Sukarno’s quiet diplomacy, patriotism, and pragmatism won the day. He picked up a minority but widely used language as the national/state language of Indonesia. In hindsight, it seems to be the right decision. Himself being a Javanese – who were almost 70% of the population – Sukarno and his colleagues introduced minority Sumatrans’ mother tongue Malay (spoken in Malaya and Singapore as well) known as “Bazaar Malay” as the state language of Indonesia, which Sukarno and his countrymen called Bahasa Indonesia or the Language of Indonesia. They did not want to impose the majority language on the non-Javanese minority for the sake of national unity in a country which is far more diverse than Pakistan. The Javanese people adopted Malay (Bahasa Indonesia) without any resistance. Then again, the situation and demography in the two countries have been very different. Nevertheless, Sukarno’s persuasion to the whole nation in a respectful tone and manner was very different from Jinnah’s arrogance and dictatorial tone, that “Urdu and Urdu alone shall be the state language of Pakistan”. In fact, Pakistan started losing its case to remain united as one nation on 21st February 1952.

The Language Movement is a historical landmark across the world. Its significance lies in the unique way the movement got its own momentum and new sets of leaders, year after year, throughout what emerged as Bangladesh in 1971. No wonder, Kofi Anan — as the Secretary-General of the United Nations — whole-heartedly supported the proposal made by two Bangladeshi-Canadians, the late Rafiqul Islam and Abdus Salam of Vancouver, to declare 21st February as the International Mother-Language Day. What an innocuous movement, apparently to make Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan, achieved at home and got international recognition as a symbol of love and respect for every language and culture in the world is something very unique in world history.

There cannot be any doubt that but for the thousands of Shaheed Minars raised at thousands of educational institutions in every town and settlements across the country East Bengalis never ever forget about their distinct national identity, which never died off while they were patriotic Pakistanis. Interestingly, most Bengalis from East Bengal/East Pakistan were willing to die for Pakistan, and many in fact gallantly defended Pakistan and died doing so during the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965.

Bangladeshis, in general, are unaware that the movement for Bengali as a state language was a positive movement for due recognition of East Bengalis as equal citizens in the state of Pakistan because they knew they had played the most significant, if not the decisive, role in the creation of Pakistan. Thanks to the sheer neglect of history in Bangladesh today – it is not a compulsory subject beyond grade eight at the high school, let alone at college/university level for arts, science, business, medicine, and engineering students, unlike the developed world – many young and educated Bangladeshis do not know what actually happened on 21st February of 1952. Unfortunately, many of them confuse the day with 25th March of 1971, the day Pakistani military started their genocidal war against Bangladesh.

As the Language Movement was a positive movement for due recognition of Bengalis as equal citizens of Pakistan, so was it not against any language, let alone Urdu and English. Sadly, thanks to the collective ignorance of Bangladeshis and their opportunist and dishonest leaders, the Language Movement has virtually become a symbol of discarding English as an essential second language of instruction in Bangladesh. The ill-informed leaders and academics believe or at least pretend so, that the Bangladeshi students do not need to learn English or any other language to become good citizens, knowledgeable, and professionally useful people. Many of them cite examples of Japan, China, and Korea, where students do all their study – from elementary schools to universities – in their mother tongue. So, the hypocritical and lame argument goes, there is no need for learning any other language, including English, for the Bangladeshi students. First of all, those who favour the abolition of English as an essential subject for education in Bangladesh – mainly people from the upper echelons – never ever send their children to Bengali-medium schools and universities. They send their children to expensive English-medium institutions at home and abroad. This is definitely hypocritical and conspiratorial to serve the vested interests of the rich and powerful because they know English-educated students are much better equipped than their Bengali-medium counterparts to get better opportunities in life.

What Bangladeshi “experts” and others who advocate pure Bengali-medium (nothing but Bengali) institutions of learning, in some cases, are not aware that other than Bengali language and literature, there are hardly any standard books and reading material in Bengali for any subject at college/university-level education. It might sound like a conspiracy theory, Bangladeshi ruling elites and their associates purposely promote three distinct mediums/systems of instruction – English, Bengali, and Madrasa – to produce three distinct classes of graduates: a) employable; b) under-employable; and c) unemployable. This is definitely what the leaders and martyrs of the Language Movement never thought of that one day their progeny would discard English or any other language in the name of protecting and promoting Bengali as a symbol of national pride and unity. It is time to educate the hyper-patriotic elements in society that no Afro-Asian language, other than Japanese, Mandarin, and Korean, is good enough for higher education in any discipline. As of today, one who wants to get higher education in any discipline will have to learn at least one European or one of the above three Asian languages. Even Turkish, Farsi, Arabic, Thai, Indonesian/Malay, Hindi, and Urdu are poor substitutes in this regard. Unfortunately, for ardent Bengali lovers, there is no way out of the situation, yet!

Last but not least, as Malaysian statesman Mahathir Mohamed once said (to paraphrase): “English language is no longer a symbol of British imperialism. Today, it is an essential tool of learning, as essential as the computer”. By the way, Malaysia and Sri Lanka, who once introduced Malay, Sinhalese, and Tamil as the only mediums of instruction at college/university level, eventually reverted to English, out of sheer pragmatic reasons. Bangladesh must learn from the Malaysian and Sri Lankan examples, if it wants Bangladeshi graduates to become competitive at home and globally in the realms of knowledge and employment opportunities.