Almost all leaders especially popular do good things to gain the status of a popular leader. But they also make mistakes. However, people often seem to get fiercely divided in portraying leaders in a balanced manner, especially posthumously.

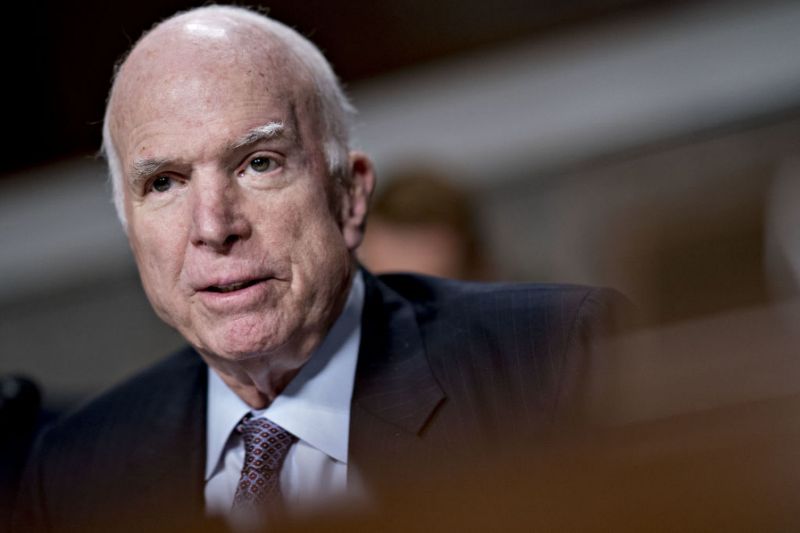

McCain, an immediate example of contradictions

Senator John McCain for example, who died of brain cancer on August 28, 2018 is a typical case where he has had outpouring of griefs and glorious eulogies and also attracted comments and observations that are less flattering.

On the flattering side Bill Goody Koontz in USA Today reports that“media coverage of the death and memorials of Sen. John McCain has dwarfed that of other public figures” including those of the two former presidents, namely Ford and Nixon and there are good reasons for this.

Among his many noted virtues, McCain has often been portrayed as a war hero for his participation in Vietnam war where he was also taken in as a prisoner and tortured and yet he was a strong advocate against use of torture as a method of interrogation of captured combatants.This is principled.

McCain also strongly advocated for establishment of diplomatic relations with communist Vietnam, his past tormentor and more recently, in his typical maverick style dramatics he in 2013 travelled to Egypt in the aftermath of ousting of Morsi, which no doubt had the support of CIA and the ruling Republican government and he himself was a Republican senator where claimed that it was a ‘coup’.

McCain’s popularity soared more recently especially after he made Trump “the political equivalent of shooting fish in a barrel” and media loved reporting his verbal skirmishes with Trump whom they loathe. McCain often broke ranks with his own party and sided with Democrats on key issues such as health care. He also strongly advocated to grant amnesty to illegal immigrants.

Former US Vice President Biden, a Democrat has thus praised McCain as the “Soul of America.”

Notwithstanding, McCain’s detractors claim that most of his “principled’ stances were lot less principled than what these made out to be, these were more rhetorical and when push came to the shove, he compromised. For example, McCain’s strongest moral voice was probably against torture of prisoners of war but as Jennifer Williams reports “his willingness to compromise his principles for the sake of politics at the height of the post-9/11 torture debate substantially weakened its power and ultimately tarnished his moral legacy” (https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/8/25/17778146/john-mccain-dies-torture-legacy-waterboarding-enhanced-interrogation-cia).

Similarly, even though many regard McCain as a war hero Brett Wilkins claims that he was more of a war criminal than a war hero, arguing that “ Even as McCain deserves praise and perhaps even admiration for the manner in which he endured the unendurable while imprisoned in Vietnam, we conveniently forget what he was doing when he was shot down over Hanoi. That day, US warplanes were bombing and strafing a light bulb factory in the densely populated capital, where thousands of innocent men, women and children were being killed by relentless American aerial attacks” (https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/08/29/john-mccain-war-criminal-not-war-hero/).

Indeed, McCain’s war mongering records are long and harsh. From first Gulf War to all the subsequent wars in the Middle East McCain supported them enthusiastically that left millions of men, women and children dead, countries destroyed, and millions displaced and counting.

So where does this leave us? How do we assess this much respected and also much reviled deceased leader? Not easy to answer. Probably acknowledgement of both good and bad would be helpful.

Closer to home

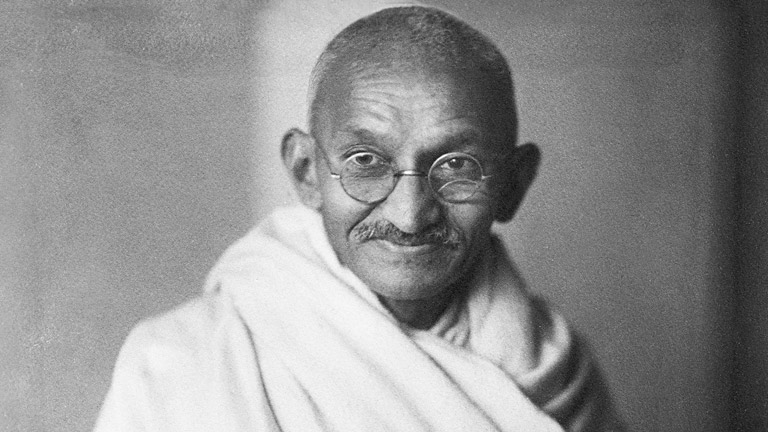

Closer to the home in the Sub-continent, we have our own share of challenges of evaluating our deceased leaders objectively.

For example, Gandhi, the Father of the Indian nation and Mahatma of the world had no doubt contributed significantly towards the independence of India. Gandhi inspired millions with his ideas and values and is revered by millions even today, not just in India but the rest of the world. But was Gandhi faultless? Christopher Hitchens points out that had India pursued one of his key anti-modernity mission– shunning factories and spinning cotton for khadi – and “unlearned” all the modern things that the British introduced, India would not have progressed to where it is today and furthermore, even though many blame Mr. Jinnah for dividing India, Gandhi’s approaches to unite all Indians especially its Muslims and Dalits were at best “condescending” if not divisive leading to the division of India and continued marginalization Dalits in truncated India(https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/07/the-real-mahatma-gandhi/308550/).

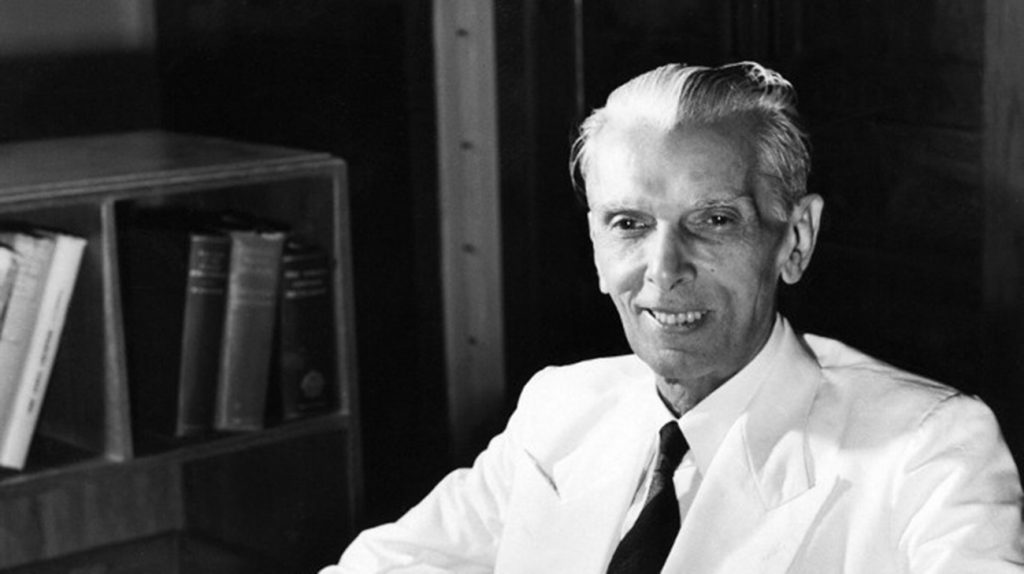

Similarly, Jinnah is a saint to the Pakistanis but a villain to most Indians and more so to most Bangladeshis who berate him for his attempts to impose Urdu at the cost of their own rich mother tongue, Bengali as the state language in the then Pakistan of which Bangladesh was its eastern wing.

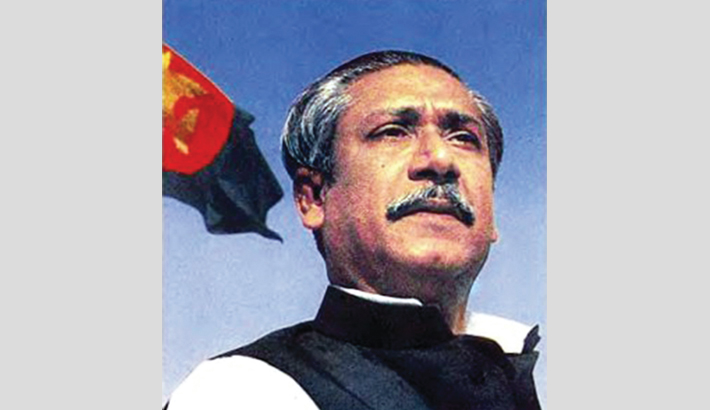

Coming to Bangladesh, Shiekh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation enjoys in equal share both adoration as well as admonition.

A BBC survey that included millions of Bengali speaking people both within and outside of both Bangladesh and West Bengal determined Sheikh Mujibur Rahman “Greatest Bengali of All Time” edging over people like Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel Prize winner, Kazi Nazrul Islam, the rebel poet, Subhas Chandra Bose, who led an army of Indian nationalists against the British Raj, Jagadish Chandra Basu, the great scientist, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, who was always a thorn in the side of the West Pakistan establishment, and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the brilliant lawyer, who went on to become prime minister of Pakistan and also the architect of the autonomy movement of erstwhile East Pakistan that Shiekh Mujib turned into a movement of self-preservation and independence (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3623345.stm).ThusSheikh Mujibur Rahman’s admirers regard him as someone who is larger than life and is beyond all criticisms who was incapable of doing anything wrong and that even if he did, these were not his making, but that circumstances compelled him to take repressive measures for which he is blamed wrongly (https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/329210/People-should-learn-from-Bangabandhu%E2%80%99s-life).

While detractors of Shiekh Mujibur Rahman acknowledge that without him there would be no Bangladesh today they also fault him for destroying democracy, tolerating corruption, promoting nepotism and favouritism in public sector and introducing extra-judicial killings as a tool of addressing political discontent and further argue that the seeds of these ills that were sown in Bangladesh during his short reign, in the country’s formative years, have since multiplied manifold and characterize the state of governance of Bangladesh today (https://adst.org/2016/03/creating-bangladesh-the-triumph-and-tragedy-of-sheikh-mujib/; https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/s/Sheikh_Mujibur_Rahman.htm).

The conundrum of contradictions and the answer

Indeed, as we can see that from far and abroad to closer to home leaders do reveal contradictory attributes? So how do we handle these contradictions?

Virtues of leaders are important as these inspire us and thus must be duly acknowledged and nurtured. But they also reveal in their almanac of deeds fair share of mistakes. How do we balance the two? Should we only highlight their good and ignore their bad so that we only cherish the good and not the bad? But if we do, we run the risk of ignoring facts and compromise objectivity. Again, by highlighting both good and bad of our leaders do we also not make them look less inspiring and in the process sacrifice our role models that we often need so desperately to inspire us to move forward?

In her TV documentary “Trans-Siberian Adventure” where she takes train trip from Beijing to Moscow Joanna Lumley of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation seems to have provided the answer (http://www.abc.net.au/tv/programs/joanna-lumleys-transsiberian-adventure/).

During her long train trip from Beijing to Moscow, Joanna stopped at a remote town of China, closer to the border of Russia. Here one evening she went to a restaurant where on opera re-enacting China’s 1949 Red revolution was show-cased. As would be expected, the key figure in the play was Mao Zedong, played by a Mao look-alike. At the end of the play, people thronged around the Mao look-alike actor for autographs. Joanna took the opportunity to ask people of their impressions of Mao. An elderly person said that Mao’s biggest contribution was that “he united the country and liberated it from foreign control”. She then asked several younger guys of their impressions of Mao. They said, “Mao was both good and bad – 50/50”. Joanna then asked them how they reconcile Mao’s good with bad. They said, “It is important to recall his good to inspire us and move forward. But it is also important to remind ourselves of his bad so that we do not repeat the mistakes he committed and make us suffer all over again”.

Precisely!

Professor M. Adil Khan is a former Senior UN policy manager

The article appeared in the Countercurrents

https://countercurrents.org/2018/09/01/the-challenges-of-evaluating-popular-leaders-objectively-especially-posthumously/

Dear sir, many thanks for this piece. hope our writers will take this path to evaluate any personality.