by Waqas Jan 23 June 2020

For a country that has since its inception based its very identity on resisting external pressures and influence, India has itself maintained a policy of playing a highly dominant role within its own immediate neighborhood. As the self-appointed heir to the British Raj, India has used this approach to consistently consolidate its influence over the entire South Asian landscape by successfully limiting the role of extra-regional players. This holds particularly true following the Post War and Cold War eras, where India’s commitment to non-alignment has since served as a defining characteristic of its foreign policy. Hence, while the likes of Pakistan, China and Afghanistan have remained a different story; India has for the better part of a century enjoyed free reign over directly influencing and dominating its smaller Eastern neighbors with minimal outside interference. Countries such as Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh in whom India has fostered a deep entrenched economic and military dependence stand as some of the most pertinent examples of what India has long carved out as its ‘strategic backyard.’

However, bolstered by its rapid economic rise over the last three decades, India has since been aspiring towards what it perceives as even further greatness. In doing so it has sought to considerably expand its role and influence beyond its immediate peripheries. For instance, the diplomatic inroads India has been consistently seeking in the Middle East/Persian Gulf to its West, and in the ASEAN states and Japan further East, present one of the clearest indications of these aspirations. They represent India’s attempts at consolidating past gains whilst envisioning an even greater role for itself outside of South Asia. Thus, laying the foundations for effectively projecting power beyond the Arabian and Andaman Seas.

There is however a certain catch to this that is worth discussing. While India’s desires for more expansive influence might be justified as a logical consequence of its great power ambitions, they present a serious challenge to its historically non-aligned approach to diplomacy. The above mentioned diplomatic in-roads India has sought into the Middle East, as well as in East and South-East Asia have taken place under the direct aegis of the last few US administrations. They also just happen to be in geo-strategic areas where the US has historically remained a major power broker. As such there has been a steadily growing alignment with US interests and foreign policy, which to no one’s surprise coalesces almost perfectly with the latter’s China Containment Policy.

Yet, whereas India’s dominant influence within its immediate periphery was built on its own commitment to non-alignment and limiting the influence of extra-regional actors, India’s forays outside of South Asia have been arguably built directly on US endorsements. Be it in the form of Mr. Modi’s Link West policy or his Act East policy, there lies an inescapable correlation with US interests in spite of however many times the word bilateral gets thrown in. In other words, pointing to India’s eventual succumbing to that very Faustian Pact which its age-old legacy of non-alignment was to meant to safeguard against.

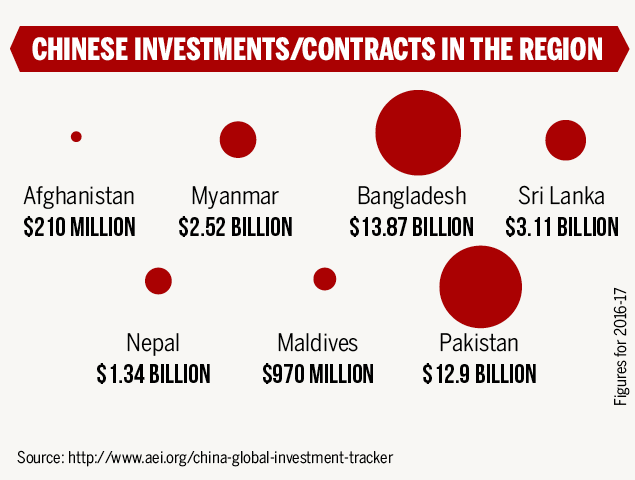

If some of the most recent developments coming out of South Asia are of any indication, then India as a result of this policy shift has directly given way to the entry of great power competition in its own backyard. It has in essence made the much vaunted threat of Chinese encirclement (String of Pearls) a self-fulfilling prophecy. What’s more, India’s increasingly hardline attitude, and its new-found confidence in overtly pushing through with its expansionist and hegemonic agenda, has only further played into Chinese hands. At the diplomatic level, all that Mr. Modi’s electorally driven foreign policy has done by annexing J&K, and through his religiously driven immigration reforms, is present China as an even more attractive alternative to an intolerant and increasingly myopic Indian leadership.

The recent map controversy with Nepal, growing security and immigration disputes with Bangladesh, the ghosts of Sri Lanka’s Tamil insurgency having returned in the form of ISIS, and the lingering tensions with Bhutan over Doklam all represent a dangerously fast-growing list of grievances that require a more tactful appeal to diplomacy. Add to that the ongoing border standoff with China, and there lies the opportunity for an unprecedented near collective rebuke of India’s credibility and power projection capabilities right within its strategic backyard.

Hence, where India had once enjoyed a near unchallenged acceptance of its role as a regional power, India’s newfound aggressiveness, poor timing and complete detachment from the reality of the situation have in a short time considerably rolled back years of diplomatic efforts and hard-won gains. Its as if Mr. Modi and his cabinet’s own hubris and growing exceptionalism has almost mirrored the failures of ‘America First’ by squandering away age-old allies and friends. What’s worse, he has put himself in a desperate position where if even if he is forced to back down now due to international pressure, he would be facing political suicide considering the violent fervor and radicalism he himself has whipped up.

No matter how his government spins the tale of a victimized India warding off Chinese aggression and encirclement, the consequences of Mr. Modi’s electorally driven sabre rattling are thus, still primarily of his own making.

- M Waqas Jan (23rd June 2020)

The writer is a Senior Research Associate at the Strategic Vision Institute, a non-partisan think tank based out of Islamabad. He can be reached at waqas@thesvi.org

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published