N Sathiya Moorthy, 8 October 2018

The last time ‘nuts’ became the talk of high-level political lingo in these parts of the world, it was in 1981. Then Pakistani President, Zia-ul-Haq, was reported as dismissing visiting US counterpart Jimmy Carter’s offer of $ 400-m American aid for two years, as ‘peanuts’. That such a private comment, by Zia to his aides, was public knowledge before he might have even completed the sentence, was an oversight of technology, or a historic accident.

The same cannot be said of President Maithiripala Sirisena’s condemnation of the State-run Sri Lankan airline serving him ‘rotten nuts’. There was no accident of history or technology-aided leak, here. The President himself came up with the fact of ‘rotten nuts’ being served to the Head of State and of Government and Supreme Commander of the armed forces.

There was however a difference between the two. Zia was talking about ‘peanuts’ which the Carters grew in their large farms back home. Sirisena was referring to ‘cashew nuts’ for which again his nation was known for along with various Ayurvedic condiments and the like.

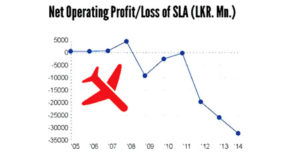

Coming as it did from the very mouth of the nation’s President, who continues to be the number one VVIP guest/customer on any Sri Lankan aircraft, even if privatised, there could not have been a better way to ‘un-sell’ the airline to foreign tourists, who are its prime customers still. Even the worst competitor of Sri Lankan, or whoever wanted to buy up the loss-making firm for a throwaway price, could not have thought of a better ‘catch-line’ to make matters worse.

If Sirisena was keen on pulling up the loss-making firm to pull up its socks, this was not certainly the way to do so. If it was also his idea to settle political scores with predecessor Rajapaksa regime, which is being targeted also for making Sri Lanka a loser in financial terms, this was a disservice to the airliner, whose responsibilities he had shared as a Cabinet Minister under President Mahinda R.

It is not unlikely that Sirisena was settling political scores with members of his own Cabinet, or with his own electoral allies now sharing power. Either way, it is like burning your own house to drive away a mosquito, and celebrate the death of the mosquito. In this case, however, the mosquitoes that the President may have targeted remain, but the house, already shaky, is gone!

Phoney call

Not long after this ‘nutty issue’, or the issue of nuts, you have President Sirisena recalling the entire diplomatic corps in a Sri Lankan Embassy in Europe. The team in Vienna, starting with the incumbent Ambassador, were not available to take Sirisena’s telephone call, when made.

It is one thing that none in the Embassy picked up the call from the President of their own nation. Less said it would have been better if lesser mortals in Sirisena’s place had tried those numbers for some urgent help for a native Sri Lankan in those parts requiring emergency consular help of whatever kind.

It is however another matter that the President of any country, or his personal staff for him, should have sought to access the nation’s diplomatic corps overseas, without going through the proper channel. In the normal course, such communication, one believes, should be – or, should have been – handled by and through the Foreign Ministry. That way, even things that a diplomatic may not be able to explain, or explain away, to his Head of State, for a variety of reasons and circumstances, may stand communicated.

Belief or loyalty?

The unusual way of the President calling diplomatic corps posted overseas directly over the head of the Foreign Ministry, or the Foreign Minister to be precise, has had its full run under predecessor Rajapaksa’s regime. There, the President was also believed to have talked directly to junior staff in individual missions, over the head of the diplomatic head of the embassy.

This had both reasons, and consequences. Under Rajapaksa, any number of non-career diplomats and non-career bureaucrats came to be appointed as the nation’s envoys and to other embassy positions, all across the world. Many of them were political aides or personal acquaintances of the President, who possibly wanted his own eyes and ears, planted wherever there was ‘action’ – or, wherever there was ‘no action’.

In posts where there was an excess of action, only of the diplomatic variety, during those crucial war years, Mahinda R reportedly wanted to be kept abreast of the briefings that he would get through the proper, official channel. Or, so his team seemed to have thought. Where there was no real action, he wanted one-time sympathises and supporters from his ‘lonely past’ rewarded for their belief in him. Some may want to describe such ‘belief’ as ‘loyalty’ – but that would not matter to Mahinda, then and possibly even now.

Trust-deficit and more

Unfortunate but true, Sri Lankan political leadership without a ‘upcountry Kandyan Goigama background’ seemed to have always felt that they were being slighted by their equally elitist ‘Colombo Seven’ civil service. Top on the list of their suspects were of course fellow-politicians of the same hue. Then came the bureaucracy with the Foreign Service pegged at the top.

It was possibly thus that President Rajapaka, at the height of the conclusive ‘Eelam War IV’, constituted a ‘Triumvirate’ to aid and assist him and also keep constant communication with the larger Indian neighbour with an equally large stake in the issues involving Sri Lanka’s war with itself. Recently in the Indian capital of New Delhi, Mahinda R told The Hindu, how his three-man team was focussed. Rajapaksa also implied that the incumbent coalition dispensation’s dispersed decision-making apparatus had failed the nation.

Before Rajapaksa, his immediate predecessor Chandrika Bandaranaike-Kumaratunga was believed to be keeping erratic time, which drove her bureaucratic aides nearer home and diplomatic corps overseas, nuts. In his time, political rival in LTTE-slain President Ranasinghe Preamadasa was known to wake up too early for any bureaucrat’s comfort and kept odd working hours. With the result many top-brass officials were believed to be keeping a camp-bed in their office, wherever they did not have a provision for a private room for his rank.

It is anybody’s guess if Sirisena pulling up the Sri Lankan diplomatic corps in Vienna was borne out of the need for him to re-activate the Foreign Ministry, as successive Presidents in his place had attempted, whenever they did not see eye-to-eye with the man heading the Ministry. Mahinda’s way of handling Foreign Minister Rohitha Bogalagama up to one level, replacing him with G L Peiris, and later giving the ministry a ‘super boss’ in the name and form of parliamentarian, Sajjin de vas Gunarawardene, are all well known.

Does it mean that the ‘outsider’ bug has begun biting President Sirisena, or is it that it was there all along, but he has come to feel it only now. As the next presidential poll approaches, is it that more and more civil servants in their senses are beginning to refuse playing ball with the political Executive(s) of the day, as has been their wont all along and the world over?

Given the inherent inadequacies that the ‘outsider’ syndrome work on incumbents in his place, and also the fact that some of the pre-Independence legacies still persist, is it that Sirisena is beginning to feel more of the heat of the kind, which keeps coming from different quarters? Otherwise a cool and competitive man, who had hidden his presidential ambitions and political cunning until the very end, just as only Mahinda R had thought was seem to be doing it, Sirisena seems to be giving vent to his political frustrations more than ever in recent weeks.

The fact also remains that over the post-JVP years of the sixties and seventies, Sri Lanka seems to have developed a new cadre of ‘Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist’ sections within the bureaucracy. Their loyalties may still lie with an ‘identifiable southerner’ withan acceptable socio-political background – leaders with a ‘committed’ image like Preamadasa, Sr or a Mahinda R. They may not have space in their midst for a ‘suspect’ (in their eyes) like Sirisena, who again could not break the glass ceiling, and get admittance into the hall of the ‘Colombo Seven’ elite!

It is not as if the urban-rural divide in the nation’s political leadership and their alternating emergence is not known or is not showing. It is that circumstances during the war years fed on it, and fed them in turn. Post-war, when President Sirisena could ask the ‘international community’, headed in this context by the US of A, to take a walk on ‘accountability issues’, there may have been others nearer home, who may want to tell him as much, but without being able to say as much – and in a ways as much as he could do at the UNGA!