The last treaty limiting Russian-US nuclear weapons, New START, expires in February. The Trump administration would prefer a comprehensive agreement including more strategic weapons and countries, especially China, explains Richard Weitz, senior fellow and director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation support his work on non-proliferation. Russia once also prioritized imposing limits on China, but now the two countries focus on defense exchanges, exercises and sales. “Through this collaboration, China has become a considerably more formidable threat to US security in the Indo-Pacific region,” explains Weitz. “For now, the Russian and Chinese governments have been content to call for declarations of intent to avoid nuclear wars, restraints on US missile defenses and military activities in space, and greater flexibility regarding Iran and North Korea.” Strengthening Sino-Russian security ties complicate treaty negotiations. Weitz urges Russia and the US to extend new START, while working to include more weapons and countries in future agreements. – YaleGlobal

Sino-Russian Ties Imperil Strategic Arms Control

The New START treaty expires in February; the US seeks to include China in new arms-control treaties, but Russia is less adamant

Richard Weitz Thursday, January 23, 2020

WASHINGTON, DC: This is a make or break year for strategic arms control. The last remaining treaty limiting Russian-US nuclear weapons, the New START Treaty, expires in February. The Trump administration wants a more comprehensive agreement that covers additional types of strategic weapons – such as Moscow’s new nuclear delivery systems. New START, like its earlier iterations, restricts only long-range Russian and US nuclear missiles and bombers.

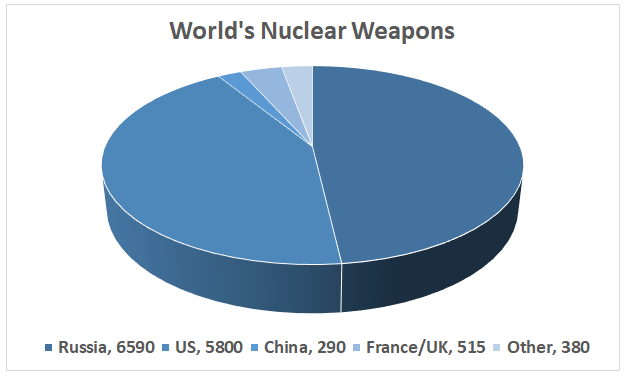

The Trump administration seeks to encompass additional countries, especially China, in future treaties. In December, the State Department formally invited Beijing to join Moscow and Washington in comprehensive nuclear reduction talks. Yet, securing Chinese involvement in nuclear arms limitations will be challenging considering Beijing naturally wants to free ride on Russian and US reductions. At November’s Moscow Non-Proliferation Conference, the director-general of the Foreign Ministry’s Department of Arms Control said that Russia and the United States must cut their nuclear forces much deeper before China or other countries would consider joining the reduction process. Fu Cong accused Washington of trying to shift the blame for the arms-control deadlock to Beijing while pursuing “overwhelming military superiority over Russia and China in all fields and with all means imaginable.”

While currently maintaining a smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia and the United States, China is unlikely to join an arms-control treaty that would formalize its inferior position. Meanwhile, the PRC Foreign Ministry recognizes the improbability that Washington or Moscow would accept a common trilateral ceiling. A spokesperson for the PRC Foreign Ministry questioned, “whether the US wants to have China’s nuclear arsenal increased to its level or reduce its own nuclear arms to China’s level?” Even so, Fu expressed interest in an enhanced dialogue on nuclear weapons doctrines “so as to avoid accidents and crises triggered by strategic misjudgment or miscalculation” as well as norms and rules for military applications of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and cyber and outer space security. Western experts have similarly called for expanded strategic stability talks on these unconventional threats.

Interestingly, Russian experts have often assessed China’s nuclear potential as substantially greater than what US assessments typically suggest. Some anticipate that China’s nuclear arsenal will continue to improve, both quantitatively and qualitatively, and approach those of Russia and the United States – with a greater number and variety of delivery systems on permanent alert status. In their view, Beijing has not deliberately sought a minimal nuclear arsenal, but rather faced technical and resource limitations, which are now eroding. The assessment of Russian analysts is that only after China acquires as roughly as large a nuclear arsenal as Russia and the United States will Beijing consider negotiating strategic limitations. Even then, they anticipate that Beijing will likely insist that any limits apply to conventional as well as nuclear forces of all Asia’s major military powers.

Russian officials had been pressing to include China in strategic arms limitation talks well before the Trump administration adopted its current position. Yet, the Russian government – whether out of aversion to antagonizing Beijing or animus for Washington or, most likely, a combination of both – now declines to challenge China’s non-participation in strategic arms-control reductions. At the PLA-sponsored Beijing Xiangshan Forum in October, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu argued that Moscow and Washington should extend New START first and then work to improve it, not discarding an existing arms-control agreement until a better one could replace it. Sergey Lavrov, as foreign minister, more recently said, “If China agrees, we will only be happy to expand the format of our consultations and negotiations.”

However, Lavrov and Nikolai Patrush, Security Council secretary, raised a question: Why should China be included, but not Britain or France, the two other countries recognized as nuclear-weapons states by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which is up for review this year. Russia’s cabinet officials resigned on January 15, after President Vladimir Putin announced constitutional changes. He quickly reappointed Shoigu and Lavrov.

For now, the Russian and Chinese governments have been content to call for declarations of intent to avoid nuclear wars, restraints on US missile defenses and military activities in space, and greater flexibility regarding Iran and North Korea. Russian analysts call for dialogue and other strategic stability measures to prevent escalation of conventional conflicts into nuclear ones. They have justified the aid Moscow is providing China on missile early warning – which Putin asserted in December would “add new quality to the defense capability of our strategic partner” – aimed to discourage China from launching its missiles on warning in a crisis. Sino-Russian military ties have substantially improved since the Cold War to include an expanding range of bilateral defense exchanges, exercises and Russian arms sales during the past two decades. Through this collaboration, China has become a considerably more formidable threat to US security in the Indo-Pacific region.

Russian experts acknowledge that Moscow sees no benefit in pressing Beijing to join Russian-US nuclear arms control because China will likely reject this pressure until the PLA has reached approximate strategic parity with Washington. However, they recognize that the growing Sino-Russian security ties will complicate any negotiations since neither Moscow nor Beijing would allow the Pentagon to have an arsenal equivalent to a combined Russian-Chinese force. At the Xiangshan Forum, Shoigu overtly attributed the loss of US support for the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty to China’s growing economic and military power, Russia’s renewed defense capabilities and the expansion of Sino-Russian security ties.

The White House’s desire to move away from purely bilateral arms control limited to a few weapons is sensible. The return of great power rivalry, the development of new strategic military technologies and other developments warrant the eventual transition to a new approach. Beijing has changed its policies on other major military issues, such as acquiring aircraft carriers or foreign bases, so a shift in the Chinese position on strategic arms talks is not a forlorn hope. With its more powerful armed forces, China should be comfortable accepting greater military transparency. Conversely, without extensive support from Beijing, strategic arms control could die. The US Senate will not ratify another such treaty without some limits on China’s nuclear forces. US officials must emphasize that, absent Beijing’s participation in strategic arms control with Russia and the United States, China will face an unconstrained arms race that it could easily lose.

Even so, the Chinese government is unlikely to change its position soon. Securing Moscow’s agreement to negotiate a new treaty including additional weapons and countries before extending the existing accord would have made sense in 2019. However, the Russian Foreign Ministry insists there is insufficient time to negotiate a new treaty before New START expires. Though strategic dialogue and confidence-building measures could help avoid miscalculation, the lack of strategic arms control would likely be counterproductive for the United States, too.

Moscow’s nuclear modernization program is in full swing; without a New START equivalent, more Russian nuclear weapons will target the United States. Additionally, the Pentagon would need to divert intelligence resources from other priorities to compensate for the lost verification and reporting data provided by the START process. A reasonable approach would be to renew New START for at least a few more years, but with a Russian-US political declaration, ideally joined by other countries, that any further agreement must include additional weapons and countries to keep arms control meaningful.

Richard Weitz is senior fellow and director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute. He would like to thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation for supporting his research and writing on nuclear non-proliferation and security issues.

The article appeared in the YaleGlobal Online newsletter on 23 January 2020

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published