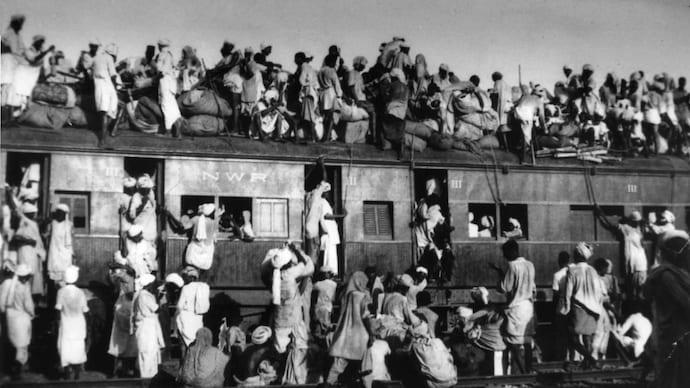

In this September 1947 photo, Muslim refugees clamber aboard an overcrowded train near New Delhi in an attempt to flee India.

by Dr. Mohammad Rashiduzzaman 16 March 2024

A band of chroniclers periodically challenge who got what and who did what immediately before and after the 1947 division of Bengal and the Punjab. Nonetheless, the Partition recounts—top-down historiographies as they are— scarcely focus on the social transition among the Muslims in what was the rural eastern Bengal that became East Pakistan and then independent Bangladesh in 1971. Drawn from assorted sources including my previous works, selected memoirs and bits of personal and family recollections, this essay centers on East Bengali grassroots dynamics in the 1940s and the early 1950s, the growing Bengali Muslim leaders in the villages and the district towns, and the Hindu-Muslim interactions in the twilight years of the British Raj.

The Hindu minority people had apprehensions about living in a prospective Muslim-majority state envisioned in the thrust for Pakistan. Yet, periodic Hindu-Muslim tensions in our vicinity did not blaze into communal atrocities as it happened in a couple of East Bengali regions or Kolkata or in the Punjab and Bihar. A small but an influential Hindu bhadralok community, the religiously mixed local officials, the town’s police station, and the younger Muslim allies maintained a modicum of peace in our neighborhoods. A handful of Hindu boys at our school hailed from the remote rural areas —-they stayed with their grandparents in our town, perceived to be a safer strip in those troubled years.

In his memoir (Jiban Jeman Dekhesi, Part 1, Dhaka, 1992), Dr. R. H. Khandkar, an internationally acknowledged economist remembered that Dhaka City, in the 1940s, was essentially divided between the Hindu and Muslim enclaves, which looked a bit like the territorial bifurcation between Hindustan and Pakistan as projected in the street roil of the 1940s. My father remembered that Rankin Street, Wari, and Ram Krishna Mission Road sections were Dhaka’s village outskirts from 1915 to 1919 while he was a Dhaka College student. But in the 1920s and 1930s, the Hindu Talukders, doctors, lawyers, businesspeople, government officers and teachers from the adjacent districts built their residential houses in those tracts. Between the two World Wars, communal disruptions also spanned in certain districts when the affluent Hindu families preferred to live in the urban areas for better security even though Dhaka and other district towns were not immune to intermittent Hindu-Muslim clashes.

Ever since the legislative and electoral reforms of the 1920s, both at the provincial administration and the local councils, the Hindu bhadralok’s prominence, as a rule, waned in the East Bengal districts. Not always acknowledged in the academic and popular histories, the Muslim legislators knocked the corridors of power in Kolkata! Their legislative empowerment trickled down to the rural areas through patronage and infrastructural development. The bulk of the students and teachers at Dhaka University were Hindus for years since 1921; nevertheless, more Muslim students came for higher education as the 1947 Partition loomed on the horizon.

Around 1945-1947, when I visited Dhaka, my father consistently sidestepped the Nawabpur Road where, from time to time, Muslims fell victims to the Hindu assailants. On the other hand, the Hindu visitors circumvented the Muslim neighborhoods to dodge sudden stabbing by the Muslim attackers. In our rural vicinity, however, violent assaults were rare—stabbing was more an urban phenomenon in those days! However, I saw it once at our local railway station when I accompanied my father—it was in 1946 or early in 1947. The victim, a Hindu widow, was the headmistress at the local girls’ school and my father knew her.

By the mid-1940s, the Hindu bhadralok no longer dominated the village councils and the local school management committees. Popular elections of the Union Parishads (village councils) and the District Boards fetched a bunch of Muslim frontrunners who represented a sprinkle of the local Muslim landed gentry, traditional village Matbars (elders), their younger scions and the newfound traders, contractors, jute brokers, retired military persons who returned home at the end of the World War II, teachers, surplus farmers, a few lawyer politicians and the Maulvis and their students from the neighboring madrassas. They stood for the new dynamics in East Bengal’s Muslim-majority territories during the explosive decade of the 1940s. Later, they survived as the vibrant energies in East Pakistan’s local and provincial politics after 1947. They were the beneficiaries as well as the challengers in the swathe that became Pakistan’s eastern province after the Partition.

Those who navigated the socio-political transition in undivided Bengal and later in East Pakistan are not necessarily the stories of the past—their inheritances continue in what is now Bangladesh. The activists of the 1940s and 1950s, who, then shouted Pakistan Zindabad, later, in their mature age, bellowed Jai Bangla and fought for Bangladesh in 1971. There is an existential correlation between those activists of the 1940s and 1950s and subsequently, the leaders of the Bangladesh movement. The present-day Bangladeshis are the heirs of the 1947 division and those who championed it—independent Bangladesh, indeed, came out of the ashes of that tumultuous and much-denigrated Partition!

A historical retracing—Bengali Muslim leadership gained an unprecedented momentum when the provincial autonomy under the Government of India Act, 1935 brought a set of reforms since the 1937 legislative election elevated A.K. Fazlul Huq as the first elected prime minister of Bengal. He distributed more jobs and supports to the growing professional Muslims. The successors of those recipients are still alive and well in Bangladesh and elsewhere! Abul Mansur Ahmed, in his unforgettable memoirs, recorded the Muslim experiences in Bengal between the two World Wars, and beyond that period. Further than the official documents, such memoirs are the alternative sources of Bangladesh’s deeply embedded history.

In their wake, more Bengali Muslim officials came to the different layers of the bureaucracy including those in the Thana (Upazila) and the district rows of governance in the 1940s. The new generation of Muslim leaders demonstrated a sense of pride and confidence. They exhibited less dependence on the powerful landed gentry—both the Hindus and Muslims. Not surprisingly, the Muslim officers in the district towns had sympathies for the Pakistan movement. In his memoirs (Kisu Smriti, Kisu Dmriti, Dhaka, 1987) Mahbubur Rahman, a senior civil servant in East Pakistan and later Bangladesh reminisced that the Hindu and Muslim officials did not take long to respectively opt for India and Pakistan according to their own religious affiliations. So, the bureaucracy was not immune to the divisive political wind of the 1940s. The brand-new Muslim leaders veered to the fresh Two-Nation Theory that carried a populist appeal for the Muslims. Those pro-Pakistan actors, however, did not normally drift to religious zealotry.

Contrary to the post-1971 Bangladeshi chetona and notwithstanding the religious content of the so-called Pakistan lobby, the campaign unlocked Muslim hopes for a territorial setting of power in post-colonial India. Such contestants were not always the strict members of the Muslim League, then at the apex of the growing Pakistan movement. Most Muslim predecessors of the ongoing Bangladeshi generation were involved with the calls for a separate Muslim state in India. Those champions also worked through the Union Board (village council) and District Board elections to pull off “regime changes” in the local governance. Such village leaders and their cohorts favored the Muslim League candidates in the 1946 Bengal Assembly elections. Politicization of the school committee elections came to the fore in the 1940s—more among the locally prominent Muslims, not so much between the Hindu and Muslim rivals. In the post-1947 era, however, the East Pakistan Muslim League, the dominant party from 1947 to 1954, assumed an exclusionary posture in its enrollment, which disappointed the younger campaigners from the 1940s. The Muslim League became increasingly unpopular over the state language issue and a bunch of East Pakistani regional grievances. The frustrated Bengali leaders and their cohorts rallied the United Front alliance, which accomplished the historic electoral victory in East Pakistan in 1954.

The younger village leaders organized relief activities during and after the famine of 1943. They hoisted slogans against the British Raj. Countless such actors volunteered to patrol their communities to maintain peace against the communal rioters. However, the local hoodlums, conspiring with the outside criminals, sometimes looted Hindu properties, to the best of my recollections of the latter half of the 1940s and early 1950s. Most public meetings were, in those days, under the sway of the Muslim leaders from the neighborhood and outsiders occasionally coming from Dhaka or the adjacent towns. Neither the Congress Party nor the enigmatic Hindu Mahasabha supporters held any public meetings during those years in our school playground. The local schools ran smoothly except that the Hindu teachers and students gradually disappeared both earlier and after the 1947 Partition. By the middle of 1947, two new Muslim teachers joined my school. More Muslim students came to our high school. Members of the Hindu bhadralok community usually led the town’s cultural activities; then by 1946-47, Muslim young men came out for major roles in the annual drama popular with both the Hindus and Muslims. Such Muslim ascendancies, however, combined to a loss of power for the Hindu bhadralok, which only amplified the pre-existing Hindu-Muslim social chasm. It was indeed the socio-political setting of the large-scale Hindu bhadralok’s migration from East Pakistan to India—the staple of the prevailing stories of the 1947 Partition and the Hindu refugees crossing the borders to India.

By early 1950s, two broad categories of the migrants crossing the border into East Pakistan were the Bengali-speakers and the non-Bengali evacuees who crowded the rural as well as the urban areas. The West Bengali Muslim officials settled down easily in East Pakistan. Bulk of the Hindu bhadralok leaving East Pakistan for West Bengal, as well, were the educated professionals—such East Bengali migrants had conceivable contacts in Kolkata and other regions in India. With initial difficulties, they steadily established themselves in friendly milieus that had shared linguistic and cultural norms. There is a genre of the Partition writings—both fiction and non-fiction—about the Hindu refugees fleeing from East Bengal to West Bengal and their anguishes. But I have come across only occasional stories about the Bengali Muslim immigrants moving to East Pakistan since 1940s.

The most advantaged non-Bengalis coming to East Pakistan quickly filled up the senior government positions abandoned by the Hindu elites. And then came the non-Bengali businesspeople and the traders in an investment- friendly territory. The non-privileged Biharis were the peripatetic refugees who fell on the margin since 1971 when East Pakistan became independent Bangladesh. They were strangers in the Bengali cultural milieu—unable to adjust in a Bengali-speaking agricultural economy. But their contributions to East Pakistan’s new jute and textile industries and the railway networks were definite.

In retrospect, I wonder if the Hindu community’s anxieties in Muslim-majority East Bengal showed up before the actual split in 1947. At the height of communal tension in the 1946/47, the Assistant Headmaster of my school preferred to leave his house keys with my father and spend time in Agartala with his relatives. My math teacher went away to his daughter and son-in- law in Assam. From 1944 to 1947 and the years immediately after the Partition, I knew that the elder sisters of my Hindu class friends and school mates were married to such young men who then worked in Kolkata, Assam, Tripura, and even other parts of India. Their older brothers and sisters preferred Kolkata or West Bengal colleges for higher studies. Occasionally, we enjoyed snacks at our friends’ sisters’ weddings. A precocious Muslim schoolfellow sporadically commented that the sisters of his Hindu playmates were married off to distant places because their parents feared that Dhaka and other East Bengal expanses might become East Pakistan. Later in life when I was a college/university student in the early 1950s, I came across senior Muslim gentlemen, born and brought up in East Bengal, but married to Kolkata ladies while they, in the 1940s, worked in that city. Those were the proxy indicators of both Hindu and Muslim concerns of Bengal falling to a division between India and Pakistan. The pre-1947 Hindus in the Muslim tracts worried about the anticipated communal turmoil and as well the dramatic uncertainties following the projected split of Bengal. The Muslim parents in Kolkata and other parts of India had similar reservations about the expected rupture along religious lines. A topic of yarns— the marriages between West Bengali and East Bengali boys and girls were, both among the Hindus and Muslims, not common events in Bengal before 1947!

** M. Rashiduzzaman is a retired academic and he writes from Glassboro, NJ, USA. Part of this narrative draws from his previous works: IDENTITY OF A MUSLIM FAMILY IN COLONIAL BENGAL: Between Memories and History, Peter Lang, NYC, 2021 and PARTIES AND POLITICS IN EAST PAKISTAN 1947-71: Political Inheritances of Bangladesh (publication expected later in 2024 by Peter Lang).