By Rahim Nasar 27 January 2020

In Pakistan, agreeing on a single Pashtun-centric narrative is a major dilemma. This is where conflicts of interests and principles begin. The structural interference of powerful institutions and assurance of limited political and electoral interests make nationalist rhetoric even more troubling. As a result, young Pashtuns with political and intellectual ideas become the riders of two boats. In this scenario, they don’t see a bright future in Pakistan either for themselves as individuals or for Pashtuns in general.

In the aftermath of the tragedy of September 11, 2001, the rise of the Talibanization and terrorism further divided Pashtun nationalist thinking in Pakistan. The US invasion of Afghanistan and the harsh response to militants in that country pushed tens of thousands of extremists into Pakistan’s erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Unfortunately, to avert the possible shift of the war theater to FATA, especially South and North Waziristan, Pashtun nationalists didn’t support a mutually agreed anti-war narrative. Their ignorance made the entire FATA a safe haven for terrorists and extremist proxies.

The second major challenge for Pashtun nationalist politics after 9/11 was the tragedy of May 12, 2007, when then-president General Pervez Musharraf exposed the real face of state authority and violated the constitution and law in a fascist way. More than 150 people were killed by hooligans led by the pro-Musharraf MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement) but there was no response by the state to such a big terrorist act. Instead, Musharraf conveyed a message that “whoever will oppose me will also suffer the same.” The very next day after the tragedy, two prominent Pashtun nationalist leaders decided to go to Karachi to find a balanced political solution in favor of oppressed and butchered Pashtuns, but bigoted attitudes and political interests turned everything around. Neither have Pashtuns received justice nor have the accused been punished.

In the 2008 Pakistani general election, after gaining a majority in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the ANP (Awami National Party) went through a brutal experience. A strange way of opposing terrorism and the Taliban was adopted – instead of criticizing the main sponsors, issues and concerns were expressed differently. At least 1,300 members of the ANP, including members of the Provincial Assembly were martyred in this dirty game. Despite all this, no serious and rigorous change was seen in the party’s political narrative in order to condemn and identify the real masters behind this fatal game. Unfortunately, this series of martyrdom continued in a more furious way. Notwithstanding the assassination of party activists on a large scale, organized propaganda against the ANP continued. The central leadership of the ANP was labeled with treason and called agents of Afghanistan and India.

At the national level, the negative attitude of the media, misrepresentation of Pashtuns and the boastful attitude of the establishment fueled hatred among tribal youth. Before the Pashtun youth rose up against the state, a peaceful but hard-pressed movement, the PTM (Urdu initials of Pashtun Protection Movement) led by Manzoor Ahmad Pashteen emerged in January 2018. Almost 95% of the Pashtun intelligentsia supported the Pashtun uprising against insecurity, terrorism, profiling and extrajudicial killings of Pashtuns in Pakistan.

The PTM laid the foundation of a powerful Pashtun nationalist narrative; on one hand, it effectively advocated the case of deprived Pashtuns in the country and on the other hand strongly criticized the security policies of the Pakistani military. The vibrant resistance narrative of the PTM stirred the entire Pakistani political hemisphere. And it also escalated Pashtun nationalist politics in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s two major Pashtun nationalist parties initially supported the movement, but over the time, things began to change. Despite serious threats and allegations against the PTM, one party continued to support the movement openly, while the other party supported in on specific occasions.

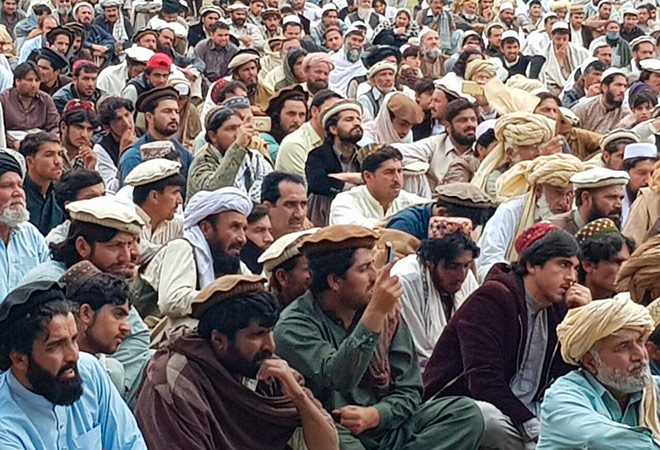

Despite this, workers of both parties supported the movement categorically. The flux of disagreement, criticism and support continued, finally, on January 12 this year in the PTM’s historic and mammoth gathering in Bannu district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Manzoor Ahmad Pashteen called for Pashtun unity in Pakistan. Pashtun nationalist parties welcomed this, but the main question is to what extent Pashtun political parties, especially nationalists, support the PTM’s narrative. The following options can possibly help to reimagine Pashtun nationalism in Pakistan.

The first and foremost prerequisite for trust and unity among Pashtun nationalists is to support the PTM. Its narrative is against neither the state nor the rule of the constitution. It is against the atrocities of forces in the name of security, destructions of war, insecurity, unrest, terrorism, missing persons, extrajudicial killings of Pashtuns across the country and the policy of good and bad Taliban who turned Pashtun land, especially tribal, areas into a death valley where thousands of Pashtuns were killed in terrorist attacks, drone attacks and military operations. (According to 2017 report by the FATA Research Center, more than 35,000 Pashtuns were killed in terrorist attacks across the country. According to a Bloomberg report in 2017 on the Afghan war, of 60,000 Pakistanis killed in the “war on terror,” the Pashtuns had the highest number of deaths.)

To support the PTM’s narrative, electoral and parliamentary interests must be sacrificed – political weaknesses should be ignored in order to create an environment of trust and unity among the Pashtuns of Pakistan.

The second-most-important option is to call for a Pashtun grand jirga in Pakistan. The jirga is a Pashtun parliament where issues are democratically reviewed and resolved. A grand jirga will surely help to discuss Pashtun grievances and create a mutually agreed strategy to secure and ensure a peaceful future for Pashtuns.

The third important point is to contact other political and democratic parties in Pakistan to ensure the supremacy of the constitution and parliament, rule of law and non-intervention of non-democratic forces in politics – the ultimate course of action for strong democracy and political stability in the state. Only a strong democratic setup and political stability can solve the problems faced by the state as well as Pashtuns.

Fourth, the natural dilemma of Pashtun nationalists is that they don’t consider other Pashtuns with different social and religious views as patriots. This is absolutely wrong and to the utmost degree negative. The influence of mullahs in Pashtun society is more powerful than that of nationalists, but the mullahs are hated because clergies have significantly exploited Pashtuns in the name of jihad, Islam and the Koran to the worst degree. Serious religious accusations have always been made against Pashtun nationalists and socialists.

Enough has already been done. Now, things should be viewed from progressive and constructive perspectives. Everyone has his or her own significance in Pashtun society. Peace, security and integrity can never be ensured without mutual understandings among nationalists, mullahs and socialists. This is the ultimate option to open a gateway toward peace and integrity.

Finally, Pashtun nationalists, socialists, intelligentsia and clergies should take a serious approach to all sorts of challenges. Pashtuns are naturally sentimental and add fuel to the flames on the smallest issue. This is utterly wrong and dangerous. Criticism should be for the sake of construction. Blatant allegations, aggressive attitudes, blasphemous language and demeaning each other should come to a complete end.