The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, one of the oldest institutions of the United States, houses documents that reveal a lesser-known but profound dimension of early American history: the presence of Islam and Muslims in the nation’s founding era. Among its most symbolic holdings are two pivotal texts: Thomas Jefferson’s English translation of the Qur’an and the Arabic autobiography of Omar Ibn Said, an enslaved African Muslim scholar. Together, these works illuminate the deep contradictions at the heart of early America, an emerging nation founded on ideals of liberty and religious freedom, yet sustained by a system that denied those same rights to thousands, including many Muslims.

.png)

Image captured from Youtube presentation

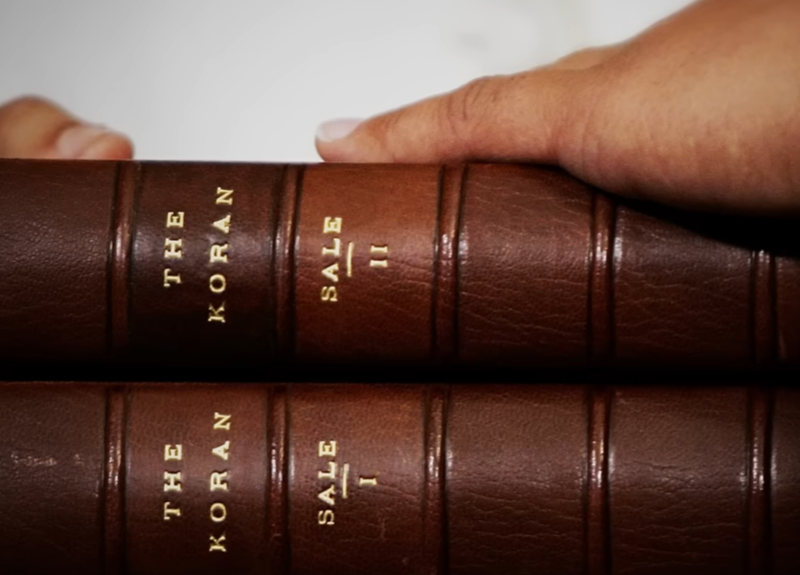

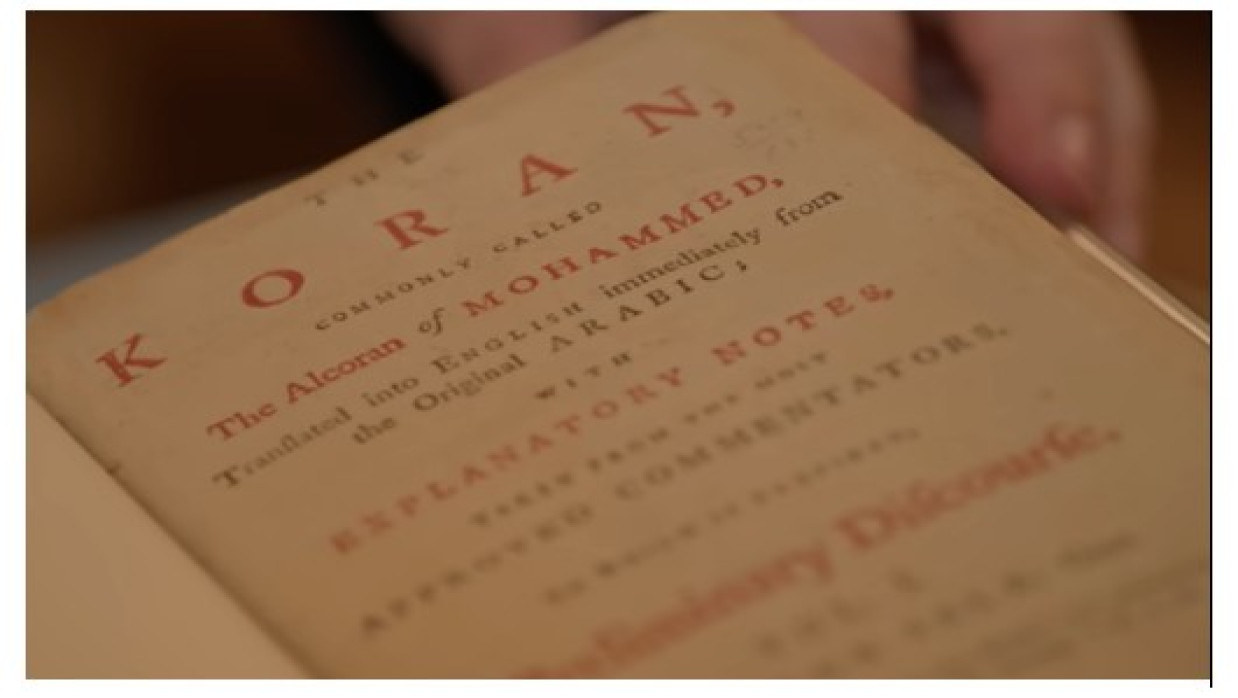

Jefferson’s Qur’an and the Global Mind of Early America

In addition to penning the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson was an avid reader of the Qur’an. The third president of the United States bought a copy in 1765 while apprenticing under legal mentor George Wythe. Jefferson’s copy is inscribed with the date he received it: July 7, 1765. Jefferson would later become one of America’s earliest Muslim sympathizers, but he did not read Arabic out of contempt; he simply saw Islam as part of his education as a political leader. By the 1700s, Muslim states and civilizations were well established enough that educated lawmakers like Jefferson saw Islam as one of the great religions and legal systems of the world.

Jefferson’s interest in comparative religion, philosophy, and law expanded his library at Monticello to over 6,500 books in his lifetime. Muslims were also active participants in international politics in the 1700s; Jefferson’s own government maintained diplomatic and trade relations with the Ottoman Empire and states in North Africa. So, reading the Qur’an was as useful to lawmakers in the 1700s as it would be for American politicians today looking to understand global affairs. Jefferson’s study of world religions showcased his commitment to what he called the “illimitable freedom of the human mind.”

Image captured from Youtube presentation

Muslim Congressman Quotes Jefferson in Taking Oath of Office

Jefferson’s Qur’an even served as fodder for modern-day politics. In 2007, Rep. Keith Ellison, a convert to Islam, was sworn into Congress using Jefferson’s Qur’an. Ellison became the first Muslim member of Congress when he won his seat representing Minnesota’s 5th congressional district. The image of the second-largest elected body in America swearing in a Muslim congressman using Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an resurfaced Islam’s long history in the United States.

Religious Freedom Beyond Christianity

Jefferson was ahead of his time in promoting religious freedom for all faiths. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, drafted by Jefferson in 1777, stated clearly that a person’s civil rights should not be “abridged on account of his religious opinion.” He later extended that support and praised religious freedom that afforded citizens the right to be “the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and the Mohammedan, the Hindoo and the infidel of every denomination.”

Jefferson went on to have his tombstone list religious freedom, the Declaration of Independence, and the University of Virginia as his greatest accomplishments. He does not mention serving as president. For Jefferson, freedom of religion meant the freedom to worship any religion or none at all. He wanted America to be a place where idol worshippers and atheists could feel welcome. However, this didn’t quite square with the fact that Muslims were already living in America as slaves.

Enslaved Muslims and the Reality of Exclusion

Of the many Africans enslaved and transported to North America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, thousands were Muslim from regions such as Senegambia (Mainly Senegal and The Gambia), Futa Toro (Northern Senegal and southern Mauritania), and Hausaland (Mostly northern Nigeria, plus parts of Niger, Ghana, and Cameroon). Several possessed knowledge of Arabic and training in Islamic education. Documented existence is found in advertisements for runaway slaves that note their ability to read Arabic, in the names of slaves in plantation inventories, and in existing Arabic manuscripts. Although Monticello’s founders espoused ideals of freedom, enslaved people were denied even the smallest taste of freedom, including practicing their religion with family. Muslims were enslaved, had their families torn apart, denied the ability to practice religious customs, and lived lives often hidden behind the veil of slavery. Jefferson himself owned more than 600 enslaved persons over the course of his life. There is no concrete evidence to indicate that Muslims lived and worked at Monticello; however, Monticello was built and maintained by enslaved labor, and their presence can be seen through the estate today, including fingerprints of enslaved children who helped make bricks for the mansion.

Similarly, George Washington’s plantation papers reference names like “Fatimer” and “Little Fatimer”.

.png)

Image captured from Youtube presentation

Omar Ibn Said: A Voice from Bondage

Perhaps the most remarkable surviving testimony of enslaved Muslim life in early America is Omar Ibn Said's autobiography. Born in 1770 in present-day Senegal, Omar was an educated Muslim scholar captured and sold into slavery in 1807. He eventually wrote an Arabic autobiography, now preserved in the Library of Congress, the only known Arabic autobiography by an enslaved person in the United States.

Omar’s narrative begins with verses from Surah Al-Mulk of the Qur’an, emphasizing divine sovereignty and justice. Scholars interpret this opening as a subtle reflection on his own condition. Though he lived the rest of his life in bondage, Omar maintained elements of his Islamic faith and identity through writing and quiet resistance.

Other enslaved Muslim figures, such as Ibrahim Abdul Rahman in Mississippi, also left traces of Arabic literacy and Islamic devotion. Abdul Rahman’s eventual emancipation after decades of enslavement demonstrates how literacy and global awareness sometimes intersected with pathways to freedom. Yet for most enslaved Muslims, liberation remained elusive.

The Long Road to Inclusion

Jefferson's vision would require centuries to take hold. State qualifications for public office persisted long into the 19th century. The Supreme Court would not apply religious clauses of the First Amendment to the states until 1947. Native American religious traditions would not be free until the late 20th century. Muslims have had to fight for their place at the table. Still, the arc from Jefferson's Qur'an to Keith Ellison swearing in seems long, but it has bent towards a more pluralistic America. Muslims have been here for a while... We've just been uncomfortable about it. Islam has been woven into American history since its inception -- it just didn't arrive on a boat.

Conclusion

Jefferson’s Qur’an and Omar Ibn Said’s autobiography tell a singular story of America’s universal aspirations existing alongside its limits of exclusion. Jefferson imagined a religious liberty expansive enough to encompass Muslims. But Omar’s life story reflects the distance between that universal vision and the experiences of Muslims who lived in early America, particularly enslaved Muslims. Acknowledging that Islam has deep roots in American history helps dispel the myths that Muslims are foreigners.

Source: Selected excerpts adapted from a PBS documentary (Public Broadcasting Service), used under fair-use principles for commentary and analysis.

0 Comments

LEAVE A COMMENT

Your email address will not be published